Germania

The Origins & Migrations of the Germanic peoples

The people of Germany appear to me indigenous, and free from intermixture with foreigners, either as settlers or casual visitants. For the emigrants of former ages performed their expeditions not by land, but by water; and that immense, and, if I may so call it, hostile ocean, is rarely navigated by ships from our world. Then, besides the danger of a boisterous and unknown sea, who would relinquish Asia, Africa, or Italy, for Germany, a land rude in its surface, rigorous in its climate, cheerless to every beholder and cultivator, except a native?

Civilization was already old in the forty-fifth century before the birth of Jesus of Nazareth. Crops had been sewn continuously in at least a few parts of the world for some fifty-three centuries. Two terrible falls had already sundered all but the most resilient of peoples from their roots. The elder races born in the last Ice Age had begun to mingle with each other, birthing new races who would soon have their era of preeminence.

Western Eurasia had been in a centuries-long period of decline. The Cradle of Civilization, the Fertile Crescent, had reached a peak in population late in the sixth millennium and early in the fifth millennium BC. The race of the Early European Farmers (EEFs), themselves largely descended from Anatolian migrants who had left the Middle East in the seventh millennium, had also peaked at that time.

The methods of agriculture and animal husbandry practiced by the EEFs had been honed over the millennia, but were still insufficient to fully colonize all of Europe. Their predecessors, the Western Hunter-Gatherers, still ruled the coastal fringe of the North Sea as well as the southern Baltic in addition to the continental highlands whose soil was too poor for the EEFs to cultivate. Across the Baltic, the Scandinavian Hunter-Gatherer race (SHGs) reigned in what is now Sweden, jealously guarding their birthright from the WHGs across the Oresund.

Lacking the ability to exploit neighboring ecologies, the EEFs turned on each other at the beginning of the 5th millennium. Vicious warfare over the limited amount of then-arable land caused their population to decline. The desperate survivors (at least in what is now Germany) turned to an Aztec-tier pantheon of human sacrifice and ritual cannibalism for succor. It brought them none. Instead, the EEF world decayed until it was overthrown.

The 45th century saw that overthrow. The WHGs on the periphery and in the interior overran the EEFs across Europe, installing themselves as a new ruling class. This “Hunter-Gatherer Resurgence” shows itself in the DNA record, with the amount of WHG ancestry in Europe’s agricultural populations increasing from about 5-10% to over 25% (depending on region) The shift in male lineages was even more extreme, with WHG male lineages (Y haplogroups) replacing up to 80% of EEF male lineages in some lands.

That overthrow was part of a broader era of upheaval. In Mesopotamia, the Late Ubaid Transition saw a substantial decline in population. The number of dated artifacts from the mid-to-late 5th millennium is considerably less than would be expected from excavated sites. The famous Indo-Europeans formed on the steppe from a collision of migrants from the Caucasus with their predecessors in the region. Similarly, the Baltic saw a major population shift. Eastern Hunter-Gatherers (EHGs) from the east invaded as the Comb Ceramic Culture. Bearing some ancestry from their southern neighbors, the Comb Ceramic EHGs made a substantial genetic impact on the eastern Baltic. How destructive that invasion was is difficult to determine from extant evidence. Nonetheless, it appears that the WHGs of the Narva Culture persisted on the coastal fringe of the eastern Baltic Sea.

The population declines across western Eurasia in the early-to-mid 5th millennium masked social progress. The new cultures, freed from some of the burdens of their prior stultifying technological conservatism by the bloodlettings, were able to advance. In Europe, the WHGs and their EEF subjects intermarried and synthesized their lifestyles. Farmers, fishermen, and hunters utilized each others toolkits to exploit a range of ecologies broader than what any of them had been able to before. The result, some four centuries after the upheavals of the 45th century, was a golden age. Sizable towns rose in the eastern Balkans, farmers settled Denmark and southern Sweden, and the Megalith Builders sailed across the English Channel to colonize the British Isles. It was not until the 36th century that decay would again set in.

A global climate shift around 3600 BC (and possibly the first plague) afflicted the sedentary populations of Europe. Some farmers shifted to more robust but lower yield crops while others warred amongst themselves for the diminishing harvests. In the Baltic, WHG Narva culture groups in the interior as well as on the coast took advantage of the temporary weakness of their EHG Comb Ceramic neighbors, regaining some of their lost territory along the coast and in Lithuania. Nonetheless, Estonia remained in the hands of the EHG Comb Ceramics. There was some mixing in the late 5th and early 4th millennia BC, but it was only after the 33rd century BC that renewed cultural syntheses would drive progress in the Baltic.

The invention of the wheel as well as the sail in the late 4th millennium BC sparked a major revolution in human affairs. Even places far from their use were shaken by the opening of new trade routes and the spread of new diseases. In Sweden, the Scandinavian Hunter-Gatherer race bearing the Pitted Ware culture destroyed the EEFs of the Funnelbeaker culture in southern Sweden. In time, they would even cross the Oresund and press into Funnelbeaker-ruled Denmark. In the steppes of what is now eastern Ukraine and southern Russia the Indo-Europeans experienced a population boom driven by their adoption of dairying. In the Baltic, certain EEFs bearing the Globular Amphora culture began pushes both along the coast as well as in the interior1.

The Globular Amphora EEFs from Poland and the post-Narva WHGs mixed together under uncertain circumstances to form the Rzucewo Culture along the Danzig Bay and Curonian and Vistula Lagoons2. In the interior of Lithuania, the Globular Amphora EEFs seem to have “gone native” - adopting the fishing-oriented lifestyle of their neighbors. In spite of these pushes, the people descended from the Narva WHGs and Comb Ceramic EHGs still endured in large parts of the region.

United under a terrible warlord perhaps dimly remembered in a number of mythologies as “The Sky Father”, the Indo-Europeans launched their third great series of conquests in the 30th and 29th centuries BC. Those conquests were deeply destructive, annihilating numerous peoples from southern Siberia to the north Caucasus to the Rhine. At least one wave of Globular Amphora EEF refugees fled north along the coast to escape the Indo-European advance, while another managed to holdout in Kuyavia.

The thick forest cover over the eastern Baltic made it an ideal holdout for the relatively dense fishing populations such as those of the Narva WHGs and the Rzucewo culture people. As it was a poor pastureland, the Indo-Europeans of the Corded Ware culture initially avoided it3, preferring the open lands of the North European Plain where they could graze their cattle. However, the Baltic’s isolation would not last forever. The Indo-Europeans learned the art of seafaring as early as the 28th century, successfully utilizing it to conquer what is now southern Sweden. There, they pushed their predecessors, the SHGs of the Pitted Ware culture, to the coastal periphery.

The Indo-Europeans began to penetrate the eastern Baltic early in the 3rd millennium. Unable to outright conquer the cold and heavily forested region, they infiltrated it. Bands of Indo-Europeans bearing the Corded Ware culture “went native” with the fishing cultures of the rivers and coasts while still maintaining some aspects of their old ways of life. Still, some parts of the eastern Baltic remained under the rule of the diverse pre-Indo-European peoples for centuries.

Beginning in the 26th century, a climate shift weakened the hunter-gatherers along the Baltic lagoons. The fish populations that had enabled the post-Narva hunter-gatherers to maintain their density and complexity declined, perhaps as the result of a decrease in water salinity. As a result, the ecological situation became advantageous to the pastoral Indo-Europeans of the Corded Ware culture who relied on domesticated animals rather than fish for their supply of protein. What had begun as Indo-European penetrations in western Lithuania and Kaliningrad turned into Indo-European conquests. Contemporary Indo-European penetrations are suggested by numerous sites as far north as Estonia disappearing or shifting to the Corded Ware culture. Even Karelia was apparently affected by these penetrations. The ancestral makeup of mixed Indo-European/Baltic Hunter-Gatherer populations shifted to favoring the Indo-Europeans, even though male lineages from the Baltic Hunter-Gatherers endured. Those conquests were far less limited in ecological and geographic scope than the previous penetrations, and reached deep into the interior of the eastern Baltic. Some Indo-Europeans in the interior ended up adopting the Textile Ceramic culture in Estonia. Nonetheless, some hunter-gatherer groups - such as the descendants of the Comb Ceramic EHGs - survived in eastern Latvia and western Estonia.

Most of Eurasia was shaken by the Crisis of the Twenty-Third Century BC. The Baltic too was afflicted. Around that time4 a cold shock dramatically shifted the local ecology for the next several centuries. That cold shock led to end of the last of the old hunter-gatherer races south of the Aland Islands, and population turnover among the Indo-Europeans. Thus was the beginning of what would form the Germanic peoples. A people born in the cold.

For six to eight centuries southern Scandinavia had been ruled by the Indo-European Battle Axe people, a northern branch of the Corded Ware people whose men largely derived from an R1a lineage. The ancestors of the Battle Axe people had overrun what are now Denmark and southern Sweden early in the 3rd millennium, replacing perhaps 90% of the previous Funnelbeaker EEF population. Slaughtering their predecessors with stone axes, they nonetheless proceeded to adopt aspects of their religion, burying their noblest dead in the great megalithic tombs erected centuries prior to their arrival. While mighty at first, they succumbed to the same forces that had led to the gradual suffocation and final destruction of the Funnelbeaker EEFs. The north’s climate and local ecologies were too harsh for them to fully exploit, while other fierce Indo-European tribes reigned to the south, blocking a southern expansion.

The cold shock of the Crisis of the 23rd Century terribly weakened the northern parts of the Battle Axe people. Archaeological proxies strongly suggest that their population declined considerably. However, not everyone in Scandinavia was weakened. The initial cold shock actually helped groups in Jutland or northern Germany who carried the male R1b-U106 lineage. Those groups had adopted aspects of the Bell Beaker lifestyle from their western neighbors, including the manufacture of a new kind of sickle which improved crop yields. They were able to open up new lands for cultivation or pasture, allowing for population growth and an increase in social complexity. Bearing daggers of stone, they were able to conquer parts of southern Norway and southern Sweden, and reigned for perhaps five centuries. However, in both western Norway as well as the Danish Isles the R1a-carrying descendants of the Battle Axe people endured in spite of the southern onslaught.

Sometime around 2000 BC the aforementioned Indo-Europeans of the eastern Baltic sailed westwards to eastern Sweden5. While all of those east Baltic Indo-Europeans carried ancestry from the hunter-gatherers who had dwelled in the region before them, their ruling class directly descended from them in the male line. That male line, from an unsampled Baltic hunter-gatherer tribe, carried the then-rare Y chromosomal haplogroup I1. Rare in the ages of the hunter-gatherers, the farmers, and the original Indo-Europeans; it was to be widespread in the age of the Germanics.

The Indo-Europeans from the eastern Baltic overran their thinly-spread predecessors in eastern Sweden, both Indo-European and SHG Pitted Ware. Both their exploitation of marine resources and lightly forested lands, perhaps derived in part from their Baltic hunter-gatherer ancestors, gave them decisive long-term demographic advantages over all of their enemies. The archaeological record shows that in parts of southern and eastern Sweden, certain areas which had previously remained unpopulated were occupied and exploited by the new arrivals. They would not remain contained in Sweden for long. Their archaeological signature, their stone cist or gallery burials, rapidly spread west and south.

The invaders from the eastern Baltic who had settled in Sweden began pressing north into Finland; and west into Norway, the Danish Isles, and eastern Jutland within a few decades of crossing the Baltic. While it is impossible to know the specific course of these migrations, the archaeological and genetic records give some hints. Stone cist burials quickly spread into Jutland from Sweden, but didn’t penetrate to the North Sea coast. Ancient DNA indicates that about 80% of the population of the Danish Isles, 75% of the population of Norway, and 45% of the population of Jutland were replaced by the eastern invaders in the 2nd millennium BC.

The population shift in Norway was fairly rapid, and is associated with the spread of cist/gallery burial practices from Sweden. Admixture dates between the newly-arrived “Eastern Scandinavian” Indo-Europeans deriving in part from the eastern Baltic and the old “Battle Axe” or “Western Scandinavian” Indo-Europeans suggest that the Eastern Scandinavians invaded Norway within a century of their arrival in Scandinavia, and had fully mixed in with them by 1600 BC. While undoubtedly violent, the invasion was not a completely successful conquest. Even a thousand years later many of the men in Norway carried the old R1a male lineages of Battle Axe Indo-Europeans rather than different and intrusive R1a lineages or the I1 lineage of the Eastern Scandinavians6. Isolated bands of Battle Axe men perhaps skulked in the periphery after defeats at the hands of the eastern invaders, conquering them or overthrowing them politically centuries after the initial invasion, but becoming absorbed by them demographically and culturally.

The story was more complicated in Jutland. Jutland, particularly the North Sea coast, were more extensively cultivated in the late third and early second millennia BC. Its population was larger than the rest of Scandinavia, making it harder for invaders to reshape its demography than the sparsely populated east and north. Its population allowed for a degree of social and political complexity, which is suggested by the variance of sizes of its contemporary burial mounds as well as its contacts with related peoples in northern Germany.

While some groups in northwestern Jutland appear to have mixed with the Eastern Scandinavians early in the 2nd millennium, others remained isolated. It is possible that groups related to the Dagger Indo-Europeans just to the south of Denmark migrated north later in the Bronze Age and mixed with the heterogenous locals. Alternatively, waves of Eastern Scandinavian migrants repeated settled in Denmark - either as invaders or as invited immigrants (long-distance bride exchanges were not uncommon in that era). In any case, the story was clearly complicated, as the male lineages associated with the Eastern Scandinavians such as I1 underrepresented relative to their overall ancestry contribution.

These migrations and struggles at the beginning of the 2nd millennium BC were simultaneous with the beginning of a new age of metallurgical advancement - the Nordic Bronze Age. The expansion of bronze metallurgy circa 2000 BC by the Eastern Scandinavians allowed for the manufacture of axes superior to any of the previous stone tools. First utilizing tools made of copper imported from Austria, the Indo-Europeans of Scandinavia were able to clear lands previously too densely forested for cultivation - adding to the lands which they had already cleared with tools of stone. This allowed for a population boom and an increase in both social and political complexity.

The increase in social complexity led to the rise of a long-lasting sun cult involving a priestess, astronomy, and possibly a dual system of political leadership. Rock art, ritual hoards, and bronze figurines found over the span of a millennium show evidence of such a cult. Remnants of the sun cult lasted into the historical era, with the Poetic Edda and the Prose Edda both referencing stories which perhaps antedated their recording by two thousand years. The persistence of a cult for such a long period in spite of the intervening political upheavals strongly suggests that the related religious beliefs were widely shared.

The Germanic branch of Indo-European is an odd one. Linguists have struggled to place it within the tree of the language family. It bears a unique set of vocabulary7 that is unlikely to be of Indo-European origin, and carries features typical of both the Italo-Celtic languages (which originated in what is now southern Germany and Czechia) as well as the Balto-Slavic languages (which likely originated in what is now Belarus and eastern Poland). Presently, the balance of evidence suggests that Germanic split off from the Baltic-Slavic-Iranian branch of Indo-European before 2200 BC (thus avoiding the satemization process), but some time after Italo-Celtic had split. Early Germanic loan words into proto-Saami (which arrived in Scandinavia no earlier than 1500 BC) strongly imply that early Germanic was spoken by at least the Nordic Bronze Age people in southwestern Finland, and thus that it was carried by an Indo-European group from the north-central Baltic (perhaps coastal Latvia) into Sweden, prior to spreading into Finland and the rest of Scandinavia. This would mean that the Eastern Scandinavians were the original speakers of early Germanic. The Battle Axe and Dagger Indo-Europeans spoke other languages which were replaced by the beginning of the Iron Age.

Bronze was an expensive alloy. It had to be made from two metals. The first was copper, which was widely available and easily sourced in the 2nd millennium BC. The second was tin, which was considerably more difficult to find. The use of bronze thus naturally drove social inequity. The few with access to bronze could wield weapons of unparalleled quality, while the many were fortunate to have access to even basic metal tools. In time, inequities are moralized. The rights and duties of both the high and low first become custom, then instinct, before a new social revolution sweeps them all away.

Such a revolution was far in the future by the time that bronze-working had spread across southern Scandinavia. Building sizes began to expand around 1750 BC, and lands both old and newly cleared were delineated. These are signs of a warrior elite that was able to control territory and regulate it with a degree of granularity. Within a century or two, that control was apparently disrupted. The sizes of houses and indeed their frequency across Scandinavia decline, suggesting that the early Germanics were affected by the simultaneous decline of the Unetice culture8 in central Europe. Nonetheless, the bronze-armed warriors appear to have solidified their control by around 1500 BC, completing the techno-social and genetic transformations that had begun centuries before.

Those transformations involved cultural, and likely linguistic, homogenization. The heavily “Eastern Scandinavian” derived warrior elites organized themselves into ruling clans which honored their dead with barrows that grew in size from 1500 BC on. While they undoubtedly feuded among themselves, they still forged a unified cultural and ethnic area, demonstrating that class solidarity among elites remained strong by the standards of the era.

The warrior class of the Nordic Bronze Age looked abroad for inspiration, rather than at home. Indeed, they had to look abroad. Sweden’s copper deposits were unknown in the 2nd millennium BC, forcing locals to import copper first from central Europe, then the British Isles, and later from the western Mediterranean. The range that the men of the Nordic Bronze Age would travel was substantial - DNA research demonstrates that some traveled at least as far south as Croatia, strengthening theories which have argued for cultural exchanges between the Mycenaean Greeks and the earliest Germanics of the Bronze Age - at least indirectly through the peoples of the Danube River Basin. Linguistic evidence suggests that the early Germanics interacted so extensively with the ancestors of the Irish in the British Isles that both shared much of their political vocabulary9. Whether as peaceful traders of amber or violent raiders carving paths which would be retrod by their Viking descendants two thousand years later, the Germanics of 1500 to 1200 BC were a part of a globalizing world.

One part of that globalization was overseas colonization. In the 17th century BC, Germanic peoples from the island of Gotland sailed across the Baltic Sea to conquer the coast and island of Saaremaa (formerly Ösel). The ancestors of the Vikings in spirit as well as blood, they appear to have struck fear deep into the interior of the Baltic. The Balts built numerous forts along the Daugava River, perhaps to defend themselves again Germanic reavers sailing up the river. This pattern - one of several in a general drive to the east - would repeated again in the Viking age, during the Northern Crusades of the Teutonic Order, and during Sweden’s early modern wars against Poland and Russia.

Mecklenburg and Pomerania, in what are now northeastern Germany and northwestern Poland, were colonized later, in the 14th-13th centuries BC. As the population of Scandinavia grew from the 16th to 13th centuries BC, more forests were felled and more fields were exhausted. While the heavily fishing and herding based economy of the Nordic Bronze Age was remarkably robust to climate shocks, agriculture was nonetheless necessary, resulting in such overexploitation of the local ecologies. The result was a southwards political expansion.

The Germanic expansion southwards was not uncontested, and occurred at the same time as other great wanderings of peoples. The Bronze Age world system centered around the eastern Mediterranean was collapsing, setting in motion events that shook all of western Eurasia. A new wave of Celtic migrations in central Europe pushed westwards, breaking the trade links between Scandinavia and the Mediterranean. To the north, a sister population of the Balto-Slavs warred with men from the Carpathians just south of the Baltic.

Germanic society faced a crisis in the 12th century as a result of these trade disruptions. Without access to the huge international markets of the previous centuries, the economic basis of their social system was undermined. Warriors had to be paid with land or imported goods - both of which were in short supply. Tools and weapons began to be reused to the point of severe wear - demonstrating that copper and tin supplies to Scandinavia had broken down. The result was a social revolution similar to that seen in Mycenaean Greece10.

The archaeological record shows that the farmsteads became smaller and more fragmented, strongly suggesting that they transitioned from a society of lords and serfs to a society of freeholders. Hamlet settlements, with one chiefly house and numerous smaller houses built around it, were abandoned. New settlements were built in an egalitarian style, with houses roughly the same size. Much of western Jutland (continental Denmark) and northern Germany were depopulated around that time. Forests grew where men had once dwelled. The Germanic peoples, once a part of the network that spanned across western Eurasia, fell into the obscurity in which they would remain until they stormed into history a thousand years later.

From the Bronze Age Collapse around 1200 BC to around 800 BC, northern Europe -really most of western Eurasia - remained in a savage state. Population proxies used by archaeologists such as pollen in ancient soil layers and distributions of radiocarbon dates from known settlements suggest that Scandinavia was emptier than it had been in over 1,500 years. Societies were neither stratified nor particularly complex. It was a dark age, but crucially an egalitarian one which would lay the foundations for the successful Germanic expansion south. The breaking of the power of the old chiefly elites opened up the grazing lands of southern Scandinavia to agricultural settlement. Those lands would become the motherland of most of the Germanic peoples.

It was only in the late 9th century BC that western Eurasia began to recover. For the previous three to four centuries political and military leaders had been unable to scale their power. Trade and raiding were the primary methods by which military elites could rise above their fellow man, but both were difficult during periods of simplification such as the Bronze Age Collapse. Control of land alone was insufficient to build a power base capable of dominating regions as extracting wealth from farmers was quite difficult. The aspiration to liberty has been present in most men across time, so elites were forced to engage in consensus politics which naturally limited the number of men which they could mobilize. This was because mobilization was based largely on personal connections rather than broadly-based institutions. In addition, the lack of metal ensured that more labor was needed to maintain the primitive economy, further limiting what existing and potential elites could exploit.

The Etruscans of the Villanovan culture in north-central Italy and the Phoenicians of the Levantine coast were among the first to relight the fire of civilization after the Bronze Age Collapse. Adopting iron metallurgy from the peoples of the south Caucasus, their labor productivity rapidly increased, and drove economic expansions which demanded new markets. Those new markets allowed for the diffusion of technology and goods. Crucially, those technologies and goods triggered economic growth across western Eurasia, allowing for the revival of social stratification and the development of states. As the Germanic peoples of southern Scandinavia lived on the fringes of the world, they were only reconnected to the western Eurasian trade network in the 6th century BC.

Less exposed to the reavers of the North Sea as well as raiders from northern Germany, society developed faster in Sweden than it did in Denmark. New growth forests were felled to open up land to cereal cultivation, allowing for renewed population expansion. Nonetheless, the peoples to the south - some known like the Celts, others unknown like the Pomeranian and Lusatian cultures - kept the Germanics hemmed in for the next few centuries. The limited range of the Germanics ensured that their dialects were periodically (though doubtfully regularly) leveled. Thus, people from Mecklenburg through Jutland into Sweden were able to understand each other’s speech.

The late fourth and early third centuries BC saw tremendous upheaval across western Eurasia. Alexander and his Greeks overthrew the Persian Empire. Rome defeated both the Etruscans and the Samnites in Italy. The Celts drove southeast into the Balkans, and, crucially for the Germanics, northeast across the Sudeten Mountains as far east as the San River Basin in what is now southwestern Poland. The arrival of the Celts in eastern Europe would have world-historical consequences.

The Celtic penetrations into northeastern Europe did not involve a great wandering of peoples. Instead, small bands of warriors seized strategic locations - particularly mines and portages - for trade. Salt, an especially valuable commodity for herders, was perhaps the initial pull for the Celtic invaders. The Celtic bands, far from their homes in southern Germany, incorporated warriors (perhaps mercenaries) from the impoverished Germanic lands in northern Germany.

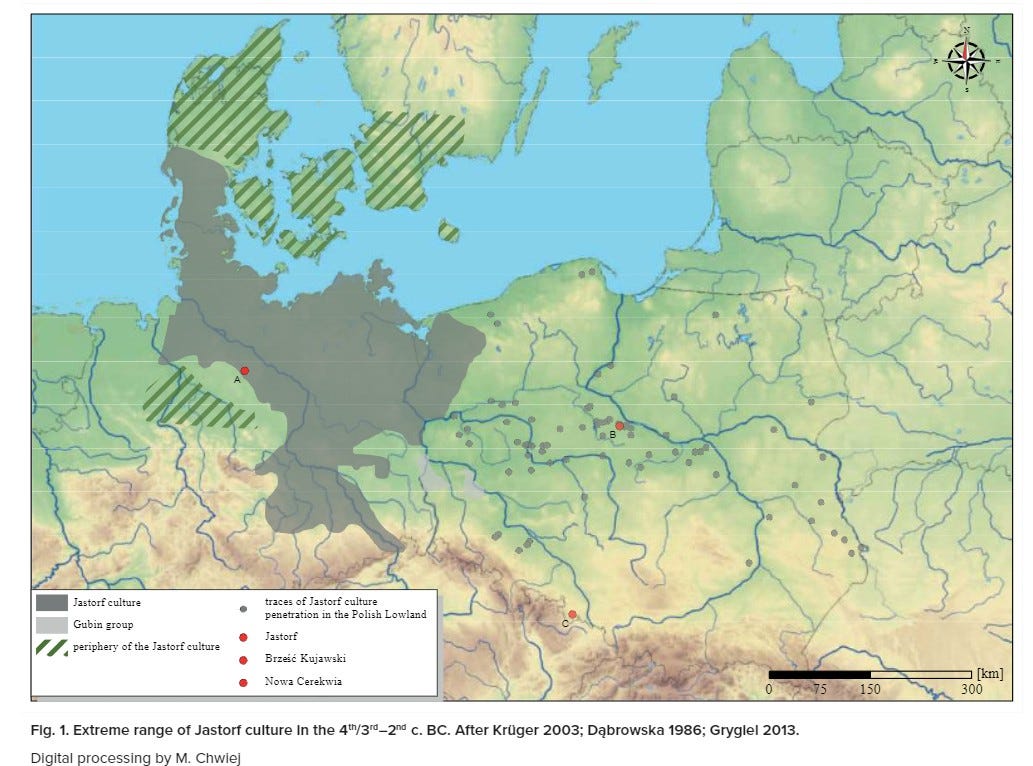

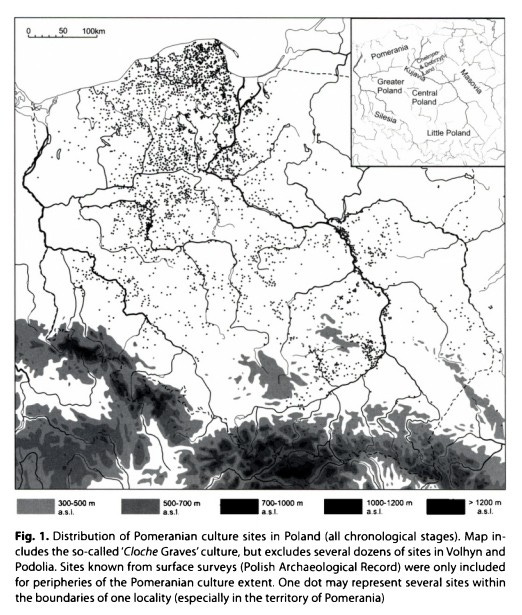

The seizures of strategic locations as well as the devastation of raids led to the destabilization of eastern Europe. The people of the Pomeranian culture, perhaps related to modern Lithuanians and Latvians, had been expanding south to exploit the power vacuum left by the decline of the post-Lusatian culture people over the previous two centuries. Their expansion was arrested by a sudden invasion of Germanics from the west bearing the new weapons introduced to the east by Celtic metallurgists. Indeed, the Pomeranian culture homeland in eastern Pomerania itself was overrun and largely depopulated by the Germanics around 300 BC. Thus the first major conquests of the Germanic peoples outside of Scandinavia were in eastern, rather than central Europe.

These Germanic conquerors and mercenaries were the first to begin the “Drang Nach Osten” - the Drive to the East of later German nationalist fame. As they settled among the peoples of the east with their Celtic lords and allies, they formed the Przeworsk culture. Some of those Germanics would drive even further to the south and east, into what is nowadays southeastern Poland and western Ukraine. There, they mixed so extensively with their predecessors that their descendants would confuse Roman ethnographers like Tacitus, writing in the first century AD:

I am in doubt whether to reckon the Peucini, Venedi, and Fenni among the Germans or Sarmatians; although the Peucini, who are by some called Bastarnae, agree with the Germans in language, apparel, and habitations. All of them live in filth and laziness. The intermarriages of their chiefs with the Sarmatians have debased them by a mixture of the manners of that people. The Venedi have drawn much from this source; for they overrun in their predatory excursions all the woody and mountainous tracts between the Peucini and Fenni. Yet even these are rather to be referred to the Germans, since they build houses, carry shields, and travel with speed on foot; in all which particulars they totally differ from the Sarmatians, who pass their time in wagons and on horseback.

The Germanization of the east and the south would be completed not by single waves of conquest and consolidation, but by waves migrants seeking to flee the cold lands of the north for sunnier and more fertile lands. Multi-ethnic confederations, first featuring a Germanic tribe as one among several, became increasingly dominated by Germanics as the centuries passed. One reason for this was the skill at arms of the Germanics11. The other was the rise of Rome.

Following the conclusion of the total struggle of the mightiest powers of the Mediterranean in the Second Punic War, history took a decades-long breath - a pause in the strife of ideologies, peoples, and states. Carthage fell, the Greek states decayed, and Rome slowly ossified - although more slowly than her neighbors. The conflicts of the barbarians far to the north were not merely unnoted, but entirely unknown. That changed towards the end of the 2nd century BC. Floods on Jutland’s North Sea coast, combined with a lengthy drought, drove the Cimbri and Ambrones (Germanic peoples proper) and the Teutones (a partially Germanized tribe of the east) to march south out of desperation.

While the Romans had encountered Germanics centuries before12, the Cimbrian War was their first contact with large numbers of Germanics. The living wall of Celts which had shielded Rome from the peoples of the north was broken in a few years of fighting. The Celts of Czechia, the Boii, were defeated and incorporated into the increasingly Celtic mass of Cimbri-led migrants. They defeated the Romans in number of destructive battles after 113 BC, then proceeded to devastate Gaul and invade Iberia prior. They were finally defeated by Gaius Marius at Vercellae in 101 BC.

Not all of the Cimbri were destroyed or enslaved by the Gaius Marius. One group, the Atuatuci, settled in what is nowadays Belgium. They were the first Germanic people to permanently establish themselves west of the Rhine, even if they were a small people. The Low Countries and Gaul were only disturbed and not reordered by those Germanic invasions - their demographics would not be reshaped by their eastern neighbors for centuries.

Southern and western Germany however, did see its demographics reshaped by waves of Germanic invaders. The Celts and others living there such as the only partially Germanized Istvaeones, close if not in their original home from which they had conquered so much of Europe, grew decadent from its trade with the Mediterranean world whilst also remaining beyond the protection of Rome. Caesar described the situation:

Now there was a time in the past when the Gauls were superior in courage to the Germans and made aggressive war upon them. Because of the number of their people and the lack of land, the Gauls sent colonies across the Rhine. And so the most fertile parts of Germany around the Hercynian forest (which I see was known by report to Eratosthenes and certain Greeks, who call it the Orkynian forest) were seized by the Tectosagians among the Volcians, who settled there: this people maintains itself to this day in these settlements and enjoys the highest reputation for justice and for success in war. At the present time, since they abide in the same condition of need, poverty, and hardship as the Germans, they adopt the same kind of food and bodily training. For the Gauls, however, the closeness of our provinces and their familiarity with oversea commodities lavishes many articles of use or luxury. Little by little they have grown accustomed to defeat and, after being conquered in many battles, they do not even compare themselves with the Germans with respect to courage.

The Helvetii, a Celtic nation on the Swiss Plateau, were hard pressed by the southern advances of the Germans in the mid-1st century BC. In 58 BC, they decided to uproot themselves from their homes and to migrate west into Gaul proper. The Romans saw this as a threat to their interests. The Helvetti planned on passing through the territory of Rome’s allies, the Aedui, as well as territory directly administered by Rome. The transit of peoples and armies until the late 20th century was extremely destructive. Supplies were carried on pack animals at a speed of a few kilometers a day, ensuring that food consumption was high and resupply was difficult. Areas crossed by migrating peoples were typically stripped barren, leaving famine and eventually mass starvation. Naturally, Rome saw this, as well as the removal of a buffer between Rome and the Germanics, as a serious threat.

Thus Caesar marched into Gaul with five legions, beginning the Gallic Wars. Lasting from 58 BC to 50 BC, Caesar not only subjugated the Gauls, but crossed the Channel into Britain and the Rhine into Germany. There, he fought with a mix of Celtic and Germanic tribes who had been displaced by the conflicts surrounding them. In Germany, the destructiveness of Caesar’s campaign can be seen in the Rhine’s palynological record. The region began to be deforested by about 250 BC for cereal farming, then reforested between 50 BC and 50 AD. Reforestation of the region, combined with the serious decline in cereal pollen in the soil layers during the post-Gallic Wars period, strongly supports that Caesar’s campaigns were quite destructive and largely depopulated parts of the middle Rhine, in line with Caesar’s own claims.

The devastation of the Rhine Valley did not have to be so long lasting. Pre-modern populations typically recovered from even 70+% die-offs within a few decades under stable political conditions such as those offered by the Romans. Lack of contraception and poor education resulted in high natality. Depopulated lands lowered mortality rates considerably by decreasing population density and thus improving sanitation while also offering plentiful land for farming and pasture, thus improving nutrition and general health.

Its depopulation was instead the result of political strife. Caesar’s campaigns across the Rhine were only temporary and punitive, but were succeeded by additional campaigns in the following decades. At least two Germanic tribes crossed the Rhine in 17/16 BC, destroying a Roman legion and devastating parts of Gaul. The Romans, seeing the Germanics as a serious threat, fortified the Rhine border over the next few years. In 12 BC, they crossed the Rhine, focusing initially on subjugating the non-Germanic tribes of Low Countries. The Roman legions eventually pressed as far east as the Elbe and established permanent bases on the Lippe. The legions appear to have largely destroyed the Celtic tribes of what are now southern and western Germany that had not already been destroyed by the advancing Germans. The Celtic world, ascending for centuries, was brutally crushed between the Germans and the Romans, its destiny denied. However, the partially Celtic-speaking and genetically and culturally distinctive Nordwestblock populations of the Low Countries - some of them known by Tacitus and Pliny as the Istvaeones - were able to maintain control of their region until the third century AD. While western Germany had contained Germanic elements since at least the third century, the Germanic element predominated after the second and became almost exclusive after the first century BC. It would remain German for the next two thousand years.

Around 1 AD, the Romans organized a pan-tribal assembly in Cologne. It was from there that they planned to run a new all-German province. Taxation of subjugated tribes was implemented by the new authorities. The Romans even established a cult center organizing all of the Germanic gods into a Roman approved religious system. That was the first step in cultural assimilation. Germania was to be civilized per the Roman model. Wealth for the faithful few, slavery and oppression for the many.

It was not to be. When the Romans were forced to cancel a campaign in Germany to crush a revolt in Illyria, one of their local auxiliary commanders Arminius saw an opportunity to consolidate his authority. The Roman commander Varus was unworried by Arminius’ rise, as he had faithfully campaigned alongside Rome and possessed Roman citizenship. It was a fatal error, not just for Varus but for Rome’s ambitions in Germany.

Arminius betrayed Varus, leading at least five German tribes to ambush Varus’ three legions. The three legions and their accompanying cavalry and auxiliary forces were annihilated. The two surviving legions who had not accompanied Varus tried to defend the Roman forts east of the Rhine, but were swept away by Arminius. Twenty-two years of Roman efforts were lost in a few weeks.

While the Romans launched several more punitive campaigns into Germany, including one which killed Arminius, they would never again seek to dominate the lands beyond the Rhine. They fortified the border, and maintained a depopulated zone for several kilometers on the eastern bank of the Rhine. It was not resettled until later in the 1st century AD, when friendly tribes were allowed to occupy the area as a living buffer against hostiles.

The struggles for Germany ensured that it was the untouched lands of the north which would replenish the populations of central Europe. The Celticized Bell Beaker populations of the Low Countries, the partially Celtic tribes along the Rhine and Danube, and the partially Sarmatian or Dacian tribes of the east had been only partially Germanized at most over the last two centuries BC. Devastated by warfare, dislocation, slavery, political collapse, and ecological destruction; their populations fell dramatically. In the centuries of the new era, new waves of Germanic invaders from northern Germany and southern Scandinavia would extensively Germanize central Europe13.

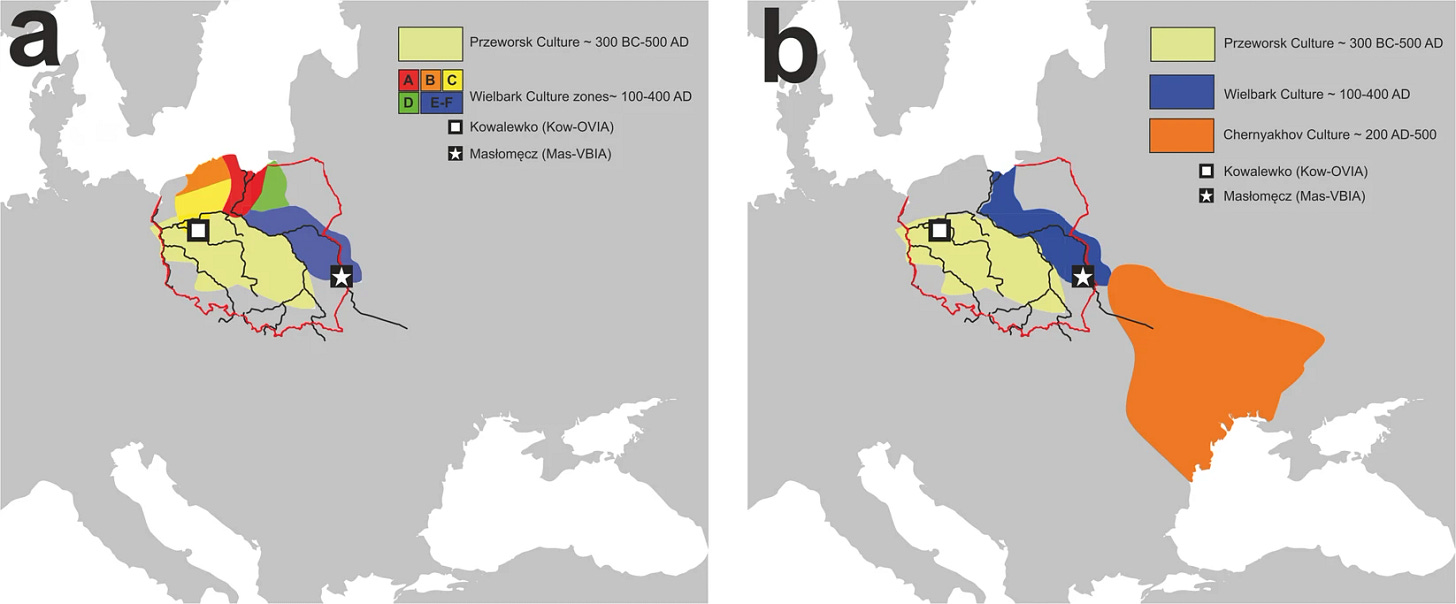

In the east, the Goths sailed south from Scandinavia (possibly their namesake Gotland) and settled the mouth of the Vistula River near modern Danzig, as noted by Roman historians Tacitus and Jordanes. There, they formed what archaeologists term the Wielbark culture. Relatively isolated from the rest of the Germanic world, the language of the Goths and those near them began to diverge. Their languages are known to linguists as the East Germanic languages.

The spread of Roman technology, as well as the increased stability of the world system following the conclusion of Rome’s transition to empire, allowed for the peoples of central and northern Europe to grow beyond the level of previous populations. Improvements in crop cultivation and animal herding are discernable in the archaeological record, in particular the expansion of the use of rye as a cereal crop in previously inhospitable areas. While the Celtic tribes of central Europe are known to have used iron scythes as early as the third century BC, their use expanded in the first centuries AD.

This population expansion resulted in the Gothic settlement area in the Vistula River basin rapidly expanding in the first two centuries AD. The Goths overcame many of their neighbors, destroying most and absorbing a few. At most a quarter of their blood came from their predecessors, or more likely even less given that those with whom they intermarried been already been partially Germanized. Similarly, population density noticeably increased in Germany. The Roman Empire, through its trade and contacts with its barbarian neighbors, had created enemies which would overthrow it in future centuries. But others would come first.

A climactic cooling around 160 AD afflicted the peoples of the north terribly. Crop yields fell, tributary and social relations broke down, and the poor starved. The leadership of a number of Germanic tribes decided to invade their neighbors. It was a decision that many leaders have made throughout history. Better to take a chance on war for food and farmland than to succumb to starvation with an absolute certainty. Thus began the Marcomannic Wars, won by Rome, but at a heavy cost.

To the east, the Germanic peoples were more successful. Some of the Goths, likely fearing starvation if they remained in their cold home along the Baltic coast, migrated to what they called Oium - now central Ukraine. In the archaeological record, the earliest layers of the resulting Chernyahov culture are almost identical to those of the Wielbark culture along the lower Vistula, confirming that the former descended from the latter. Testing of DNA from Chernyahov burials confirms that the Goths were a large fraction of the population, although they incorporated peoples from the Balkans as well. The Balkans people with the Goths were likely the Getae, a Dacian people who became so integrated with the Goths later on that historians such as Jordanes understood them to be part of the same nation.

The civilized world had a respite from serious struggles for half a century following the conclusion of the Marcomannic Wars. The Severan dynasty fought a brief war from 213-4 with the Alemanni confederation in southwestern Germany. In the east, near what is now Odessa, the Goths destroyed the city of Olbia. The Romans responded by reordering the frontier with expanded fortifications and a number of forgotten intrigues.

Those fortifications held while the empire was strong, but were as fragile as all works of men when the empire faltered. Longstanding problems with political succession, plague, and a climactic cooling all weakened the empire terribly. The result was the Crisis of the Third Century. Lasting from 235 to 284 AD, the Roman Empire was invaded from without by Germanic peoples as well as the Sassanids, while also seeing internal rebellions which seized control of a large fraction of the empire.

Rome was still quite strong early in the crisis. Her legions were able to penetrate into Germany, devastating the west and defeating the armies of the Alemanni and others in the 230s. But as the internal situation of the empire worsened, she was increasingly unable to deal with foreign invasions. The Goths, previously held back in Dacia, raided into Moesia in 248 and invaded Thrace in 249. Other Germanic tribes attack Rome’s frontier fortifications along the Danube and Rhine beginning in 252. By the end of the decade, they were raiding into Italy and Spain. The areas closest to the Rhine frontier were largely depopulated. Archaeology and numismatics suggest that the Romans only began rebuilding in the area in the 270s, during Aurelian’s “restoration of the world”. Despite brutal Roman campaigns in southwest Germany in the 270s, sizeable territories (in green below) were lost forever to the Alemanni. The local Roman population appears to have fled or have been tortured to death. Roman monuments and religious statues were defaced in sacrilegious vandalism by the Germans. In the north, in the Low Countries along the Lower Rhine, the Nordwestblock tribes were annihilated or expelled by the Germanic Frisians and Franks.

The Roman state was reformed by Diocletian from 284 to 305 AD. He expanded the size of the bureaucracy, increased the granularity of state authority, and raised the authority of the executives. His reforms made the empire strong again, but brittle. It never fully recovered from the Crisis of the Third Century. Across the Rhine and Danube, the Germanic peoples also reorganized their tribes. Large scale warfare in the 3rd century drove the consolidation of tribes into larger confederations, and then forced the formalization of those confederations into proper kingdoms. Germanic veterans of the Roman military appear to have played a role in this, applying their knowledge of organization to their own peoples and enabling them to expand at the expense of their less organized neighbors.

Rome’s reconsolidation of its Rhine frontier lasted several decades, but was ultimately ephemeral. The Alemanni crossed the Rhine again in 357 and 366. They again devastated the region, depopulating it for decades to come, and clearing the path for their grandchildren.

In the east, Rome’s Danube frontier fared little better in the face of the Germanic threat. The Gothic King Ermanaric intervened in the dynastic struggles of the Eastern Roman Empire, forcing the Romans to launch a punitive campaigns against him across the Danube. While successful in 367 and 369, the fighting in the 370s and 380s proved less fortunate for Rome. The Goths, desperate for refuge from the advancing Huns, fled Ukraine for the safety of the Roman Balkans. Unable to fully defeat the Goths, the Romans eventually allowed them to settle in the northern Balkans and to govern themselves. While the Romans had settled foreign tribes within their empire before, their failure to bring the Goths under imperial administration demonstrated that their power was brittle and would soon be broken.

Savage tribes in countless numbers have overrun all parts of Gaul. The whole country between the Alps and the Pyrenees, between the Rhine and the Ocean, has been laid waste by hordes of Quadi, Vandals, Sarmatians, Alans, Gepids, Herules, Saxons, Burgundians, Alemanni and – alas! for the commonweal! – even Pannonians

Saint Jerome

On 31 December 406 the River Rhine froze. The decay of the Roman state’s finances as well as the withdrawal of border guards from the Rhine for the defense of Italy left Roman defenses in the Upper Rhine weak. As a result, hundreds of thousands of Germanic tribesmen, as well as other peoples like the Sarmatians and Alans crossed into the Roman Empire with little resistance. They desired the wealth of the empire, and its better climes, but more importantly security from the growing power of the Franks as well as the predations of the Huns.

The Romans managed to hold the northern frontier with the Germanic peoples for a time, but as the interior of their empire disintegrated the Franks who had been aiding them in holding the border made increasing gains at Rome’s expense. The Vandals, deriving from East Germanics of the Przeworsk culture in eastern Germany and Poland, migrated to Iberia, and then proceeded to North Africa where they seized power and established a kingdom which lasted until 534. The Suebi also migrated to Iberia, but chose to settle in the northwest. The Burgundians remained in Gaul, establishing a kingdom whose antagonism to Rome proved so intractable that the Romans used the Huns to destroy it in 437 before allowing its reestablishment further north14. The Alemanni expanded their realm along the Upper Rhine, where they would remain even after their subjugation by the Franks in 496.

The Romans made efforts to incorporate the migrating tribes, perhaps then better described as nations due to their size, into their political system. They were designated federates - sub-state entities allowed their own particular and autonomous government, but which were obligated to provide soldiers to defend the empire if called. As tax revenues decreased across the 5th century, the Western Roman Empire became almost entirely reliant on these units. Germanic generals and other figures became increasingly prominent and powerful within the Roman governments as a result.

The new “system” of Roman governance caused the collapse of the western empire. The federates and increasingly isolated Roman officials warred amongst each other, devastating the lands of the dying empire. Cities were burned, fields abandoned, trade raided, and manufacturing localized. The population, already in decline from a decrease in crop yields as the result of another climatic cooling, collapsed.

This collapse was discernible in the archaeological record, and is now discernible in the genetic record as well. Pottery, the most common enduring good in the archaeological record, made at major manufacturing sites across the western Mediterranean is succeeded in higher (and thus more recent) soil layers by inferior pottery manufactured by local artisans. The pollen in soil layers from the empire is largely from crops, while the pollen in soil layers immediately following the empire is largely from wild-growth plants. Urban sites shrink in size or are outright abandoned.

The blood of the people themselves changed too. Since the Roman triumph in the Second Punic War the population of Italy had become first increasingly Greek, and then increasingly derived from the eastern Mediterranean. Urban areas across the empire, and in Iberia more generally came to resemble Italy as Rome consolidated her hold. The mass die offs from the plagues in the second and third centuries AD reshaped the demographics of the western empire somewhat, as hundreds of thousands of migrants and slaves from beyond the northern borders of the empire such as the Carpi settled within in and relatively isolated rural populations partially replenished urban and more exposed areas. The total rather than partial collapse of imperial authority in the west in the 5th century resulted in a further decline of the eastern Mediterranean derived populations in the west.

After the death of Emperor Theodosius in 395, the Goths considered their federate agreement with Rome to be void. A barbarian people, they considered agreements to be with men rather than with states. Part of their nation, the Visigoths, proceeded to devastate the Balkans, including Greece, and launched several invasions of Italy. Failing in 402 and 406, they succeeded in 408. They sacked Rome after several sieges in 410, and then devastated southern Italy before the death of their leader Alaric. They then migrated to Gaul and Iberia, establishing a kingdom which lasted until the Moslem conquest in 720.

In Iberia the Germanic and Alan migrants had less of an effect on peninsular demographics than would be expected. While the Germanic migrants who crossed the Rhine numbered in the hundreds of thousands, fighting and starvation thinned their numbers considerably. Comparable migrations with recorded numbers such as the Kalmyk migration back to Xinjiang or the Helvetti return to their home suggest that even mildly unfavorable conditions lead to the deaths of perhaps two-thirds of the migrating population.

The other part of the Gothic nation, the Ostrogoths, fell under Hunnic rather than Roman domination in the 4th century. Much like their cousins to the south, they preserved political autonomy and were able to assert themselves when their overlords were troubled. The conflicts that emerged within the Hunnic realm following the bloody draw at Catalaunian Fields in 451 and Attila’s death in 454 allowed them to migrate to Roman territory in the western Balkans, where they were granted federate status. Following the overthrow of the Western Roman Emperor by Odoacer and his coalition of Germanic Scirii, Rugii and Heruli federates in 476; the Eastern Roman Emperor sought to preserve at least some imperial authority in Italy by recognizing Odoacer as a client. Odoacer’s decision to align with rebels against the Eastern Roman Empire changed Constantinople’s perspective. They offered the Ostrogoths Italy if they could overthrow Odoacer. They accepted and succeeded, founding a kingdom which lasted until 554.

The Ostrogothic Kingdom had a troubled existence. The Eastern Roman Empire under the Emperor Justinian invaded Italy in 535, starting a war which lasted until 554. The length of the war, along with a cold shock created by a volcanic eruption and a plague, depopulated Italy even more severely in the sixth century than the devastation of barbarians invasions had in the fifth. While scholarly estimates of the population of Italy place it around 10 million in the fifth century and 8 million in the sixth (compared to 15 million at the peak of the empire), the genetic impact of perhaps 200,000 Germanic migrants imply a far greater fall into the low millions. Finds from the Exarchate of Ravenna, an Eastern Roman polity, agree that mid-1st millennium decline of Italy’s population was severe enough that the empire had to bring in settlers from the eastern Mediterranean and the Maghreb to consolidate its authority. Weakened by the fighting, famine, and plagues, the Eastern Romans were unable to stop the Lombards, another Germanic group, from invading Italy with a group of 20,000 Saxons in 568.

In Britain, the Roman population died entirely as the urban areas were destroyed by the Germanic Angles, Saxons, and Jutes invading by sea in the decades following the Roman withdrawal. The unassimilated Celts were pushed to the west and north over the centuries, becoming the Welsh and Cornish. However, enough were assimilated to the Anglish (eventually English) for them to account for perhaps two-thirds of the modern ancestry of the English - the rest coming from the Germanic Anglo-Saxon invaders.

By 500, most of the former Western Roman Empire was in the hands of Germanic rulers. The Franks controlled most of the Low Countries and northern Gaul. The Visigoths controlled parts of southern Gaul and Iberia. The Burgundians ruled parts of eastern-central Gaul. The Suebi controlled northwestern Iberia. The Ostrogoths ruled in Italy and the northwestern Balkans. The Alemanni ruled in the Upper Rhine. The eastern half of England was under the control of Angles, Saxons, and Jutes. The Vandals ruled Tunisia, Algeria, and Libya. Certain peripheral peoples asserted their authority - notably the non-Indo-European Basques in the western Pyrenees, the Berbers in the Maghreb, and the Celtic Bretons in northwestern France.

The mass migrations of the Germanic peoples west, as well as the devastation wrought by the Huns and the wars of succession after Attila’s death left much of the Germanic world empty. Poland, eastern Germany, Ukraine, and Hungary, all cold and exposed to the fearsome horsemen of the steppe, would come to be settled by new peoples in the following two centuries - the Slavs. While some Slavs had been part of the Gothic Kingdom of Oium as far back as the 3rd century and their Germanized descendants participated in migrations as far west as Iberia, they only became prominent in history after the beginning of the sixth century - after the last of the Goths of central Europe had migrated to Italy. The remnant Germanic populations of the east had little of the material culture of their migrant cousins. The men forming their political structures had either been killed or left, leaving essentially isolated rustics to fend for themselves against only slightly better organized but similarly economically robust waves of Slavic migrants. Replacing half of the population of the western Balkans and two-thirds of the populations of Poland, Czechoslovakia, and eastern Germany in the 6th and 7th centuries; Slavic populations dominate large parts of eastern Europe even today.

The mass exoduses of the Germanic peoples, the devastation wrought by the Huns and the wars of their successors, and the collapse of the polities of central Europe obliterated Germanic historical memory. While the Germanic peoples of the 1st century AD, Tacitus’ time, made claims to history going back centuries, those of the later centuries could barely even remember Attila and the leading families of his era. Christianization accelerated this decay, shifting the burden on maintaining historical memory to those more concerned with events in the Levant than northern Europe.

The Germanic rulers of the former Western Roman Empire were aware of their primitivity. Where Roman civilization survived, they often sought to conserve and integrate it within their new realms. Those whom had been pagan or whom adhered to Arian rather than Chalcedonian Christianity adopted Catholicism, then intermarried with their new coreligionists while adopting their Romance languages. While most accepted the suzerainty of the Eastern Roman Emperor, all but the Lombards in Italy asserted their true sovereignty by the end of the 6th century. Thus the Italians, French, and Spanish came to be - albeit as far more regional peoples such as Tuscans, Catalans, Provencals, Neapolitans, and others before the consolidation of truly national identities. There, the Germanic story ends. It continued in the north.

The Germanic peoples maintained long-distance contacts with their cousins in Central Europe sometimes for decades after making their migrations into what was once Rome. The Saxons of England, Germany, and Italy are known to have kept in touch, with the last even returning to Germany after finding that they disliked living under the Lombards. The return of some of those Germanic migrants back to Germany resulted in a brief increase of Mediterranean ancestry in the peoples of southern Germany, spread by both Roman men and women. That mixed population did not persist in Bavaria. Frankish campaigns in the region appear to have opened it up to settlement by a Germanic tribe from Bohemia - the Baiuvarii. The Baiuvarii, on the periphery of the Frankish world, replaced their predecessors over the course of the later 6th and early 7th century. They eventually gave their name to the region and polity.

The mixed ancestry did persist to the west, in the parts of Germany directly administered by the Franks as well as in their new territories in Gaul. By the 8th century it had even diffused to Denmark, and to the rest of Scandinavia by the 11th through slaves and international marriages. The breakup of the Frankish realm in the middle of the 9th century presumably reduced the amount of intermarriage between the peoples of France and Germany, but it never wholly halted.

The 2nd millennium AD saw several trends among the Germanic peoples. Those along the Rhine intermarried with the peoples of France and took on an increasingly French character. Those in the north preserved and indeed expanded their Nordic roots as the result of the repeated invasions by Denmark and Sweden. Those in the east intermarried with Slavs and Balts as they established colonies as far east as Siberia - if they weren’t acculturated Slavs or Balts themselves. The English fell under the rule of the Normans, a French-speaking but Viking-derived people, reorienting them permanently from northern and towards western Europe. In all cases, the ancestral purity of the Germanic peoples discussed by Tacitus faded. The process of purification - the breaking of the Germanic peoples on the Roman frontier and their subsequent replacement by more isolated, warlike, and purer Germanic tribes from the north - ended forever as the Germanics became part of Western civilization and Christendom.

Some of the eastern territories lost to the Slavs in the 6th and 7th centuries were gradually clawed back over the course of the Middle Ages. The Ottonian Kings of Germany had launched invasions of the Slavic lands in what are now northeastern Germany as early as the 10th century, following in the steps of the Danes who had been trying to conquer Germany’s Baltic coast since the 9th century. Conquest was accompanied with conversion to Christianity and cultural Germanization. While Jesus of Nazareth was famously vague about his views on government, by the Middle Ages Catholics had come up with a system of righteous life and government. That system forced the civilizing of the Baltic and Slavic pagans; replacing their raids with trade, concubinage with marriage, tribes with polities, and custom with law. As the institutions enforcing that system spoke German or Latin, those subject to them came to speak German in time.

While the Germanization of the Baltic coast was led by knights and priests, in Czechia and Poland it was led by merchants and tradesmen. The Slavic lands, less developed than the West, desired the manufactured goods and sometimes industries of their neighbors. Unable or unwilling to develop them on their own, they sponsored the settlement of Germans across their lands on occasion, beginning in the early 13th century. While Germans were often assimilated by their Slavic neighbors, they weren’t always, and came to become the majority of the population in a number of cities and regions - famously the Sudetenland.

The Little Ice Age, in particular its worst cold shock in the 17th century, led to a number of devastating conflicts in Germany called the Thirty Years War. About a third of the population died, with a greater share of the population dying in in the northeast. The contemporary Wars of the Three Kingdoms weren’t as devastating, but still killed a twentieth of the English population. Sweden, then a major power, escaped devastation itself in the 17th century through its military successes, but succumbed to a brutal series of invasions in the early 18th which broke its power.

The die offs in the Thirty Years War and general underpopulation led to German political leaders inviting settlers to repopulate their domains. The Hapsburgs resettled Croats in Austria, while the Hohenzollerns invited French Huguenots to Prussia. These migrations, disproportionately drawing from military, religious, and commercial elites, numbered in the tens of thousands, don’t appear to have made a substantial genetic impact even if their products proved influential. The assimilation of Slavs in Prussia as the result of Protestant liturgies and Austria as a result of state Germanization policies were far more influential demographically. Today’s Germans are on average about 10-15% Slavic in ancestry, although there is a great deal of variation. There are a noticeable number of Germans whose ancestry is best modeled as 50% Slavic15.

Political consolidation of the German polities had been a gradual process from the 15th to the 18th centuries, but was suddenly accelerated by the Napoleonic Wars. At the conclusion of the wars, the hundreds of German polities had been reduced to a few dozen. Prussia, founded in the former Slavic and Baltic territories of what is now northeastern Germany and northwestern Poland, united all but Austria into the German Empire in 1871. Following Germany and Austria’s defeat at the hands of the Western Powers in 1919, a pan-Germanic movement took power in Germany. Aiming at dominating most of the Old World, they launched the greatest war in history. They succeeding in briefly unifying all of the Germanic states of the world other than the United States, Great Britain, Sweden, and Switzerland into their empire prior to their total defeat.

The range of the Germans was cut dramatically after the end of the Second World War. They lost much of the Baltic coast, Silesia, Czechia, as well as their settlements across the Balkans, Ukraine, and Poland. Shorn of the eastern territories which had brought the Germans their militaristic vision and the generals to act upon it, they turned to the West. The old dream of the Germanic tribes on the Rhine and Danube frontiers of the Romans, to become wealthy through trade and industry in the shadow of a greater empire, replaced the later dreams of freedom and power which had led Germany to a third ruin in 1,500 years.

In addition to the linked resources, I drew heavily upon the following works:

The Invasion of Europe by the Barbarians by J.B. Bury

The Fall of Rome by Bryan Ward Perkins

Empires and Barbarians by Peter Heather

Germania by Tacitus

The Oxford Handbook of the European Bronze Age

The Oxford Handbook of the European Iron Age

this is relatively new research, so does not show on most maps (such as those of Wikipedia) of the Globular Amphora Culture’s reach

hopefully future DNA research will illuminate the circumstances and magnitude of the mixing

The Corded Ware Indo-Europeans in central Europe did have a bit of ancestry (5-15%) from the hunter-gatherers of the Baltic. This likely originated from unknown 4th millennium Baltic hunter-gatherer migrations into Belarus & north-central Ukraine (Neman culture?) rather than the ephemeral penetrations discussed in the paragraph below.

give or take a few centuries - the sedimentary and archaeological records are notoriously difficult to date for this period. It could be that I’m completely wrong.

This appears to have been part of a general westwards expansion out of the eastern Baltic - the Trzciniec culture of Poland, formed around 1800 BC, seems to have derived (in part) from similar Baltic groups, although they ended up carrying the I2 haplogroup rather than I1

See the discussion of Y haplogroups in Supplement 1A starting on page 58

I would guess from the aforementioned Baltic Hunter-Gatherers who reached a high positions among the Baltic Corded Ware

I suspect that the rise of the Tumulus culture and western spread of the Celtic languages as well as southwards spread of the Italic languages from southern Germany is the cause of this. More research is needed.

per Koch, the words for king, kingdom, tribe, hostage, servant, and fortified settlement were shared in early Goidelic Celtic and early Germanic

while also attested in archaeological record, Thucydides seems to reference this episode of Greek history as well

my suspicion is that this woman, who died among the Etruscans, was a slave rather than a migrant

Swedish campaigns in Germany & Poland in 16th-18th centuries - as well as the devastation that they wrought - are probably the best modern approximation to the repeated Germanic expansions out of Scandinavia. The Swedes conquered the outlets of the Weser, Elbe, Oder, Daugava, and Vistula rivers at various points; using the rivers to resupply their troops as they campaigned deep into the continent.

where it would eventually become a region in France, Burgundy, known for its political prominence in the Middle Ages

A number of prominent German families trace their patrilines to Slavic chieftains who converted to Christianity and accepted the overlordship of the Holy Roman Emperor

Great work, especially on the Pre-historic era.

It is easy to forget with terms like EEF, Corded Ware, etc that these people had their own kings and heroes, their own Gods and rituals. Countless tribes and nations lie buried in the Earth whose very names have been forgotten.

You writing makes the past came alive in a way that the coldly scientific terminology of archaeology can often obscure.

Makes me feel like a young boy again, excited to discover exotic races far away in the distant past.

What a tour de force!