“Zeus the Father made a third generation of mortal men, a brazen race, sprung from ash-trees; and it was in no way equal to the silver age, but was terrible and strong. They loved the lamentable works of Ares and deeds of violence; they ate no bread, but were hard of heart like adamant, fearful men. Great was their strength and unconquerable the arms which grew from their shoulders on their strong limbs. Their armor was of bronze, and their houses of bronze, and of bronze were their implements: there was no black iron. These were destroyed by their own hands and passed to the dank house of chill Hades, and left no name: terrible though they were, black Death seized them, and they left the bright light of the sun.”

Never before had mankind risen so high as it had by the 13th century before our era. It had been seven centuries since the end of the terrible cold epoch that had shaken civilizations from Spain to China. It had been at least three centuries since the eruption of the volcano at Thera had briefly dimmed western Eurasia. While the peoples of the Indus Valley had never recovered from the change in climate, elsewhere civilization had recovered and advanced beyond its previous heights.

Trade ships crossed the Mediterranean and Arabian Seas while caravans traveled overland, connecting the civilizational centers of Eurasia. The barbarian world too was linked into the Eurasian trade networks. Amber collected by the Baltic peoples made its way up the Vistula, down the Danube, through the Black Sea, and across the Mediterranean to Egypt. In return, the Baltic peoples as well as the Germanic peoples in Sweden received metals both practical and precious from the Mediterranean. Tin traveled from as far as Afghanistan in the east and Britain in the west to the eastern Mediterranean. Swords manufactured in the Middle East were exported all the way to Malwa in western India. Baboons and other exotic goods were transported from the Horn of Africa to Egypt in return for pottery, tools, and glass.

Economic complexity was mirror by political complexity. The Hittites, reigning in what is now central Turkey, organized a trade embargo against the Mycenaean Greeks. The Mycenaeans administered overseas colonies at least as far east as Sicily. Middle Eastern states formed alliance blocs to balance out the rises or declines of their neighbors.

International trade was one of the easiest source of revenues for Bronze Age states. Caravan stops and sea ports could be cheaply garrisoned with troops and customs officials due to their limited size. Alternative sources of revenues, such as temples, could be difficult to obtain money from due to the strength of clerical establishments which (judging from Egypt’s history) could have tenuous if not outright hostile relationships with the secular state. Even more difficult was extracting revenue from the peasantry, which could violently attack tax collectors or rebel against the authorities. Records from the Classical and Early Modern eras (specifically Roman and Ottoman Egypt respectively)1 suggest that perhaps an eighth of state revenues could have been generated by customs collected at sea ports.

Those revenues would have been essential to the large states of the late Bronze Age. Bureaucrats and soldiers had to be paid, irrigation and building projects financed, grain stockpiled for periods of drought. A decline in customs revenue would directly threaten state finances, and in the medium-run threaten the stability of the state. Unpaid soldiers and hungry artisans in particular were serious threats.

With such a significant fraction of state revenues at the mercy of stable international systems, a serious shock was bound to cause terrible problems not just in the civilized world, but also in the barbarian periphery. Such a shock came in the latter half of the 13th century BC - the first part of the Bronze Age Collapse that would see the states and societies disintegrate across western Eurasia. While the first climate shock lasted from roughly 1250 to 1100 BC prior to a brief return to normal climactic conditions, it was followed about a half century later by a renewed decline in rainfall that lasted until the 9th century BC. The Bronze Age Collapse appears to have happened in two parts - the first saw state and economic disintegration, the second a wandering of peoples greater in genetic impact although not likely in magnitude than the famous wandering of peoples that accompanied the collapse of the Roman and Sassanid Empires.

The climate of the eastern Mediterranean shifted to become cooler and drier in the late 13th century BC. Rainfall declined, and drought ensued. The archaeological records suggests that Greece suffered the worst. The result was that the Mycenaean Greeks turned first outwards in desperation for food - becoming a large part of the Sea Peoples who devastated the eastern Mediterranean prior to their defeat at the hands of the Egyptians - then inwards in a revolutionary turmoil that destroyed most of the Greek cities. Both the expeditions abroad and the revolutions at home were still dimly remembered eight centuries later, and recorded by Thucydides:

Even after the Trojan War, Hellas was still engaged in removing and settling, and thus could not attain to the quiet which must precede growth. The late return of the Hellenes from Ilium caused many revolutions, and factions ensued almost everywhere; and it was the citizens thus driven into exile who founded the cities. Sixty years after the capture of Ilium, the modern Boeotians were driven out of Arne by the Thessalians, and settled in the present Boeotia, the former Cadmeis; though there was a division of them there before, some of whom joined the expedition to Ilium. Twenty years later, the Dorians and the Heraclids became masters of Peloponnese; so that much had to be done and many years had to elapse before Hellas could attain to a durable tranquility undisturbed by removals…

Thucydides’ reference to the Greeks emigrating even after the Trojan War prior to the era of revolution has been confirmed by both Egyptian records, ancient DNA, and the Bible. The Philistines, or Peleset to the Egyptians, settled in what is now the Gaza Strip. From their realm there, they and their heavily mixed descendants waged wars recorded in a number of Biblical texts. In Greece itself, writing was forgotten, and history survived only in myth.

The breadth of the reavings of the Sea Peoples in the late 13th and early 12th centuries compounded the problems caused by the climatic shift. In peaceful times, poor harvests could be made up for by the import of food from abroad. As early as the late 13th century, both the Hittites and Ugarit dealt with the famines in their realms in Anatolia and Syria by importing grain from Egypt by sea. However, the breakdown of the sea trade in the succeeding decades made that more expensive. Food had to be shipped overland - if it was to be shipped at all. Unable to recover from famine, Ugarit was destroyed in the early 12th century. The Hittite realm was overrun by invaders from the east, west, and south.

The world system centered around the Eastern Mediterranean first frayed, then disintegrated entirely after decades of chaos. In addition to food, the long distance transportation of tin was important to Bronze Age economies. It was needed, along with considerably more plentiful copper, to make bronze. Bronze was used in weapons and tools, so disruptions of supplies prevented economic growth by forcing reversion to more primitive tool use. For instance, the Bronze Age Collapse led to the cession of metal tool use in the Don Basin of what is now eastern Ukraine and southwestern Russia. The locals reverted to the usage of stone and bone tools.

The breakdown in trade and communication can be seen in the disease record as well. While strains of hepatitis as far back as the neolithic were shared across Europe and the Middle East, the fragmentation caused by the Bronze Age Collapse was so extreme that the previously common strains largely died out. It would be new strains of hepatitis that would recolonize western Eurasia in the Iron Age, four centuries later. The Bronze Age Collapse was thus clearly not limited to the eastern Mediterranean, but was experienced by most of western Eurasia and eastern Africa.

Cushitic-speaking pastoralists descending from migrants from the middle Nile region around Dongola had dwelled in the Horn of Africa for perhaps a thousand years by the time of the Bronze Age Collapse. Nonetheless, they did not dominate the region. The Ethiopian Highlands remained out of their reach, the hunter-gatherer race there reigning as it had since time immemorial. Even in the lowlands the Cushites had not conquered all. Their stone weapons gave them little advantage over those of the races of hunter-gatherers - particularly in areas where the fishing was rich and the hunter-gatherers numerous.

The port town of Adulis was a place of contact between the lowland pastoralists and the highland hunter-gatherers. There, goods from the African interior were sold to Egyptian and South Arabian merchants who shipped them across the Red Sea. Artistic portrayals of the locals in the mid-second millennium BC suggest that Adulis, as part of Punt, was inhabited by at least two peoples. One of those peoples was short and steatopygous like the hunter-gatherers. The other, portrayed alongside cattle, was likely a group of Cushitic pastoralists, possibly the ancestors of the Afar people.

That arrangement was shattered by a decline in rainfall in the late 2nd millennium BC Ethiopian Highlands - the same decline in rainfall which affected the Egyptians down the Nile. Semites from southern Arabia crossed the Red Sea, first invading the lowlands where their influence can be seen in a sudden change in burial types. Towards the second part of the collapse, in the early 1st millennium, they pressed into the Ethiopian Highlands to become the ancestors of the Amhara and Tigray, among others. In the highlands, they founded the first known kingdom of the region - D’mt. The hunter-gatherers of the highlands were absorbed by the invaders, although some in Ethiopia’s southwest have survived to the present. The invaders brought with them more a more advanced social model as well as new technologies, allowing their population to far outgrow their predecessors in the early 1st millennium BC. That social model included a revival of trade which is documented in the Book of Kings and the Book of Chronicles, which reference the Queen of Sheba, a Sabaean member of a trade caravan which visited Israel in the 10th century BC.

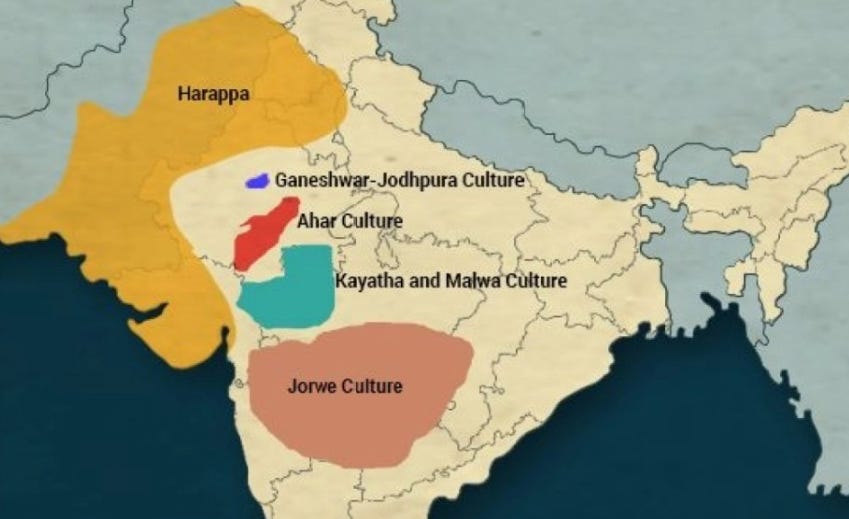

The convulsions reached across the Indian Ocean as well. The Jorwe culture in the northern Deccan, never a peaceful society, entered a period of population and cultural decline. Planned settlements decayed or were abandoned. Farmers either adopted pastoralism or were overrun by pastoralists. In the centuries to come iron-wielding invaders would overcome the diminished remnants of the once-great people.

Nonetheless the collapse on the western coast of India wasn’t as bad as elsewhere. Trade across the Arabian Sea with Oman, Iran and Bahrain continued, although to an unknown extent. In any case, it was a great decline from the long voyages of the Indus Valley Civilization centuries earlier, which had journeyed to the Red Sea and traded with the people of the Horn.

Far to the north, across the Thar Desert and Hindu Kush, reigned the Yaz and Chust peoples in what is now Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan. Like their contemporaries in the South Caucasus, they had experienced an era of chaos some three centuries prior (in their case likely due to spread of chariot warfare), and were spared the misery of the Bronze Age Collapse. Towards the end of the Bronze Age Collapse, they would sweep into Iran and establish the first Iranian states on the plateau - Media, Parthia, and most famously Persia. The previous rulers - Elamites, Aryans, and largely forgotten peoples related to certain groups in the Caucasus - would be swept away.

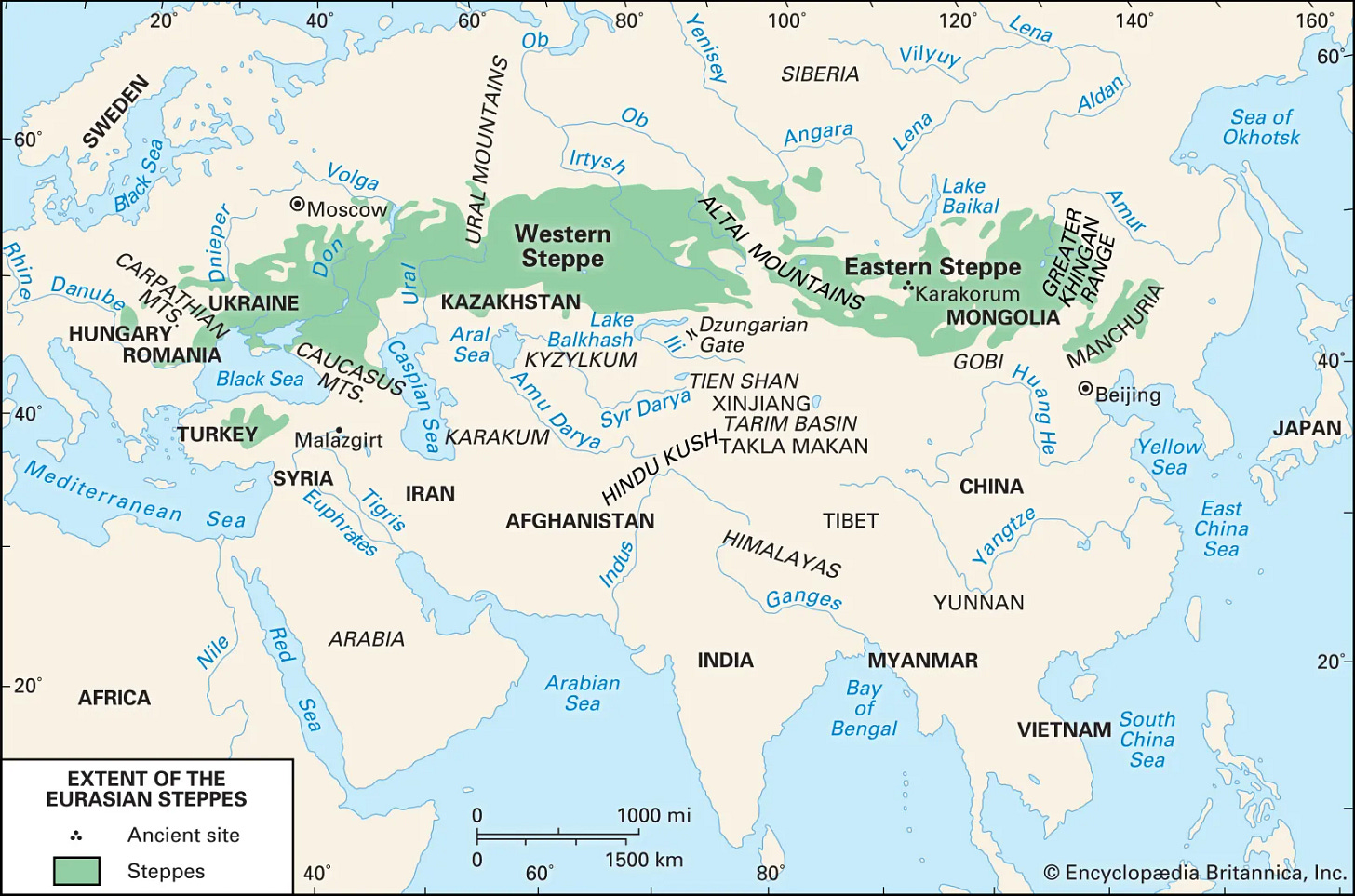

Their northern neighbors on the steppe were not so fortunate. Dominated by Indo-Iranian-speaking groups for centuries, a number of different archaeological cultures developed, suggesting a variety of competing steppe confederations. That cultural diversity was replaced by relatively cultural homogeneity at the end of the second millennium BC. Commensurate with the decline in cultural diversity was the decline in cultural complexity (at least in pottery stylization) and settlement size. Together, the picture is one of mass die offs and extensive warfare that resulted in the triumph of a series of steppe confederations stretching from Hungary to the Altai, followed by its disintegration prior to the rise of the Scythians.

The disintegration of the Indo-Iranian confederations on the steppe offered opportunities for their hunter-gatherer and fisherman neighbors in the forests to their north. Originally hailing from what is now Yakutia, Uralic-speaking tribes had become integrated into a great trade network that stretched across Siberia and European Russia by the middle of the 2nd millennium BC. While they had been primitives at the time of their contact with the steppe peoples, their remarkable intelligence (still noticeable even in today’s psychometric results among their Russified descendants) enabled them to quickly match and surpass their neighbors in metallurgical sophistication.

In the beginning, the story of the Uralics was one of integration. Groups of them migrated as merchants or smiths into the Indo-Iranian societies which had settled in the forests of the southern Urals and the surrounding areas in the mid-2nd millennium. The Mezhovka people for instance were mostly of Indo-Iranian origin, but had a detectable amount of Uralic blood. In the 12th century BC, the Mezhovka people took advantage of the Bronze Age Collapse weakening the other Indo-Iranian groups to their west. They crossed the Ural Mountains and reached as far west as the Vyatka River.

Deeper in the forests however, other Uralics brooded in the long Siberian winters. They saw the Indo-Iranians to their south as well as the now-forgotten races to their west as slaves at best. Their word for slave - “orya” - derived from the Indo-Iranian endonym “arya”. The mighty steppe lords who proudly reigned from Hungary to Mongolia and from Siberia to India were mere prey for the fierce Uralic tribesmen.

As the Bronze Age Collapse dragged on for centuries, the Uralics found opportunities. In western Siberia, one Uralic group overran the Mezhovka people east of the Urals around the 9th century BC. They slew their men and took their women, forming what would become the ancestors of the Mansi people, as well as the linguistic (but not genetic) predecessors of the Hungarians. In the Kama River Basin west of the Urals, the (probably Indo-Iranian speaking) Maklasheyevskaya Culture was overrun around the same time by the ancestors of the Udmurts and Komi who had first absorbed some of the surviving EHGs in the far north before migrating south. They replaced perhaps a quarter to a third of the local population. Other Uralic groups pressed directly west over the Urals without an Arctic detour, conquering the Baltic peoples living on the upper reaches of the Volga River in the early 1st millennium.

The Uralic expansion during the Bronze Age Collapse did not reach Estonia. It was not until centuries later, in the Iron Age, that Estonia would be added into the Uralic world. Instead, Germanic peoples from the island of Gotland sailed across the Baltic Sea to conquer the coast and island of Saaremaa. The ancestors of the Vikings in spirit as well as blood, they appear to have struck fear deep into the interior of the Baltic. The Balts built numerous forts along the Daugava River, perhaps to defend themselves again Germanic reavers sailing up the river.

The Germanic world was far smaller in the Bronze Age than in the present. Its heart was in Denmark, southern Sweden, southern Norway, and north-central Germany. To its south and west were the mighty Celts. To the east were the Balts and the Slavs. Its exports to the rich markets of the eastern Mediterranean had made its chieftains wealthy. Their wealth, like the wealth of the Mycenaean Greek chieftains, created a deeply unequal society. The Germanic chiefs built larger graves and larger homes than they had previously.

The first part of the Bronze Age Collapse in the 12th century BC affected the Germanics only indirectly at first. The cutting of the trade routes in the eastern Mediterranean as well as the expansion of the Celts to the south led to the end of bronze imports to the Baltic. Old bronze weapons were reused for generations until they were finally disposed of in burials. However, the soil was becoming exhausted after centuries of agriculture. Food imports could have sustained the population for a time, but the economic basis of society was fragile.

It seems that the Germanic society faced a crisis in the decades that followed the Bronze Age Collapse. Without access to the huge international markets of the previous centuries, the economic basis of the Germanic chiefs was undermined. Retainers had to be paid with land or booty taken on raids - both of which were in short supply. At least some of the chiefs followed the example of the Mycenaean Greeks and decided to launch serious campaigns of overseas conquests. While the Greeks had some successes, the Germanics appear to have failed outside of some ephemeral colonies in Estonia and Latvia that they would not reclaim for over two thousand years. One campaign, in what is now Mecklenburg, saw the Germanic invaders fight and lose a major battle against enemies who appear to be the kin of the modern Slavs (though whom likely spoke a different branch of Indo-European). Thousands were slain.

With defeat abroad, the chiefs faced revolution at home much like the Greeks. The archaeological record shows that the farmsteads became smaller and more fragmented, strongly suggesting that they transitioned from a society of lords and serfs to a society of freeholders. Hamlet settlements, with one chiefly house and numerous smaller houses, were abandoned. New settlements were built in an egalitarian style, with houses roughly the same size. Much of western Jutland (continental Denmark) and northern Germany was depopulated around that time. Forests grew where men had once dwelled. The Germanic peoples, once linked to the civilized world, fell into the obscurity in which they would remain until they stormed into history a thousand years later.

To the south of the Germanic peoples dwelt the Celts. The Celts, represented archaeologically by the Tumulus Culture, had spread from their original homeland in southern Germany and Czechia2 into what is now eastern France in the middle of the 2nd millennium BC, possibly taking advantage of the chaos following the Eruption of Thera. Whether or not they displaced the previous population or merely asserted themselves as a new ruling class is uncertain.

What is clear is that around 1300 BC what is now France was divided between a steppe-ancestry rich Celtic northeast and center, a Ligurian or at least non-Celtic Indo-European southeast, an Atlantic coastal fringe ruled by Indo-European groups lost to history, and the western Pyrenees ruled by the ancestors of the Basques (a non-Indo-European people who nonetheless had a substantial amount of Indo-European blood, similar to the Etruscans).

While proto-Celtic has a word for “iron”, which implies that it could have been spoken no earlier than 800 BC. However, the shared root for “iron” in both Celtic and Germanic shows that the word “iron” could have simply spread from one branch of Celtic to another. If the Tumulus Culture was indeed the proto-Celtic culture, then a divergence of two branches of Celtic may have begun as early as 1500 BC. The first Celts to migrate west likely spoke the Q-Celtic languages3 - the language ancestral to Celtiberian and Goidelic. The Celts who remained in their home in southern Germany by contrast spoke the P-Celtic languages ancestral to Gaulish and Brittonic.

The archaeological record of southern Germany shows two periods of settlement destruction that coincide with the two phases of the climactic shift that accompanied the Bronze Age Collapse - one in the late 2nd millennium, and the other in the early 1st millennium BC. The climactic shift as well as the breakdown of trade led to an era of social revolution and decline in cultural sophistication. While a shift from burials to cremations had begun in the previous centuries, it became dominant in the Celtic world in the Bronze Age Collapse - giving the name to the Urnfield Culture.

While social revolution and foreign adventures had featured in the contemporary turmoil in Greece and Scandinavia, the Celts were unique in that their foreign adventures succeeded spectacularly. Taking advantage of the power vacuum in northern Italy due to the Italic Terramare Culture’s exodus to the south4, the Celts poured through the Alpine passes and established Cis-Alpine Gaul. From there, they pressed into what is now southeastern France and replaced a noticeable fraction of the population, although some of their predecessors appear to have endured in certain areas. The Celts proved to be much better inhabitants of southern France than their predecessors. Palynological and archaeological proxies suggest that their arrival coincides with a period of substantial population growth and economic development. The Gauls would originate there, spreading north over the succeeding centuries while marginalizing and absorbing (if not destroying) their Q-Celtic predecessors.

To the northwest, the Q-Celts overran most of the Low Countries (apparently excluding Frisia) after they came under the influence of the P-Celt migrants from southern Germany, then proceeded to launch an invasion of England which over the course of the next three centuries replaced about half of the population. They brought with them traditions such as the deposition of bronze weapons in waterways. Some Celts in Normandy remained closely related with their relations in England, suggesting some sort of cross-channel political entity formed in the Bronze Age Collapse that lasted into the Iron Age. Such cross-channel contacts would be noted as late as the 1st century BC by Julius Caesar in his Commentaries on the Gallic War. The archaeological record supports Bronze Age Collapse-era England as a war-torn and devastated land, with numerous ringforts constructed to offer shelter to people fearful of violence. It would be centuries before the population would recover.

Other Celts, seeing opportunities in a rapidly depopulating Iberia, crossed the Pyrenees and established themselves across the peninsula. Iberia’s diverse geographies allowed certain peoples to hold out against the Celtic onslaught, but the genetic impact was still quite dramatic. Areas known to have been inhabited by the Celtiberians had about a third of their population replaced, while areas that remained non-Celtic had between a tenth and a fifth of their populations replaced over the succeeding centuries. While there were undoubtedly countless tales of forgotten romances between dashing Celts and lovely Iberians, the ugly realities of slavery and concubinage should not be forgotten.

While the breadth of the Celtic conquests during the Bronze Age Collapse is staggering, the Celts were far from an invincible people. Indeed, their conquests were highly contingent upon the collapse of others rather than their own successes - a pattern which would be repeated in the Migration Period where politically and economically robust but relatively primitive peoples such as the Germans, Berbers, Arabs, Sarmatians, Basques, and Bretons thrived as their sophisticated ruler or neighbor, the Roman Empire, collapsed.

Ireland burned during the Bronze Age Collapse. Once one of the richest and best developed regions of western Europe, the breakdown in trade cut Ireland’s supply of metal. The peoples of Ireland warred among themselves, constructing hillforts to defend themselves from their rivals. Many of those hillforts were burned. In the end, Ireland’s social and political structures disintegrated entirely. Nonetheless, the genetic influence of the Celts doesn’t appear nearly as great as it was in neighboring England, suggesting that the Q-Celtic takeover may have been through elite replacement or religious proselytization. In any case, the population of Ireland wouldn’t recover for a thousand years.

While the Crisis of the 23rd Century had merely dimmed the light of civilization, the Bronze Age Collapse extinguished it entirely in most of western Eurasia. Millions died and technology regressed. Political structures collapsed, social networks disintegrated, and barbarians overran settled populations. Only in Egypt and parts of the Levant, Mesopotamia, and the Caucasus did civilization endure - and even there it held by threads. While the successes of the first three are fairly well known and discussed in Eric Cline’s excellent book on the Bronze Age Collapse in the eastern Mediterranean, the late archaeologist Antonio Sagona suggests that it was the south Caucasus’ endurance which would prove to be the most important.

In Greek mythology, Prometheus steals the secret of fire to men. As punishment, he was bound to either Mount Kazbek or Mount Elbrus (both very close to Colchians lands). The ancestors of the modern Georgians, the ancient Colchians, had been experimenting with iron smelting since the mid-2nd millennium BC. Perhaps with the collapse of the Hittite realm in the Bronze Age Collapse and the loss of their knowledge of iron, it was the Colchians who spread the knowledge to the fallen world, ushering in the Iron Age and renewing the progress of civilization in the early 1st millennium BC. It would probably not be the only Greek myth alluding to Colchis’ well-deserved reputation for metallurgical knowledge. If so, then Greek mythology may hold the dim memory of the role of the Colchians in spreading iron metallurgy.

In addition to sources linked, I relied heavily on The Oxford Handbook of the European Bronze Age, 1177 BC: The Year Civilization Collapsed, The Urals and Western Siberia in the Bronze and Iron Ages, and The Archaeology of the Caucasus

See The Roman Empire and the Silk Routes and The Ottoman Age of Exploration for a discussion. Twitter excerpts for Ottomans & Romans.

genetic evidence for multiple waves of central European migrants into northern Italy from 2200 to 800 BC, the popular linguistic theory of Italic and Celtic being part of the same branch in the Indo-European language family that split early in the 2nd millennium, and extensive contact between proto-Celtic and proto-Germanic languages which could have happened no later than 500 BC all support an Italo-Celtic urheimat in southern Germany and Czechia rather than the Atlantic Coast. As a result, the 2nd millennium BC archaeological culture originating in southern Germany and Czechia, the Tumulus Culture, can be seen as representing the earliest Celts.

The Celtic Languages, 2nd Edition by Martin Ball and Nicole Muller has a discussion in chapters 1 and 3 of the possible or even likely split of proto-Celtic into Celtiberian-Goidelic (Q-Celtic) and Gaulish-Brittonic (P-Celtic). Shared features between the Insular Celtic languages (Brittonic and Goidelic) can be attributed to Brittonics establishing themselves on top of an originally Goidelic Celtic population in England and Wales in the mid-to-late 1st millennium in my admittedly unexpert opinion.

in addition to joining the Sea Peoples, the Italics would settle in Lazio, Apulia, and Sicily. There, they mixed with the locals and become the Italic peoples known to history as the Latins, Samnites, and Sicels. The archaeological record is clearest in Lazio, where Etruscan/Villanovan cultural influence is interrupted during the 11th century BC, and the center of wealth moves away from the coast to the Alban Hills - in line with Roman folk memory.

Masterful post, well worth the time it took to make it, thank you for this.

A wonderful quote from Hesiod and overall an excellent post.