The Sea People

Alexander the Great tread in the footsteps of forgotten Greeks

Following his triumph over the Persians and their subjects at the Battle of Issus in 333 BC, Alexander the Great advanced south into Lebanon. The Phoenician city-states knelt to him, with the exception of Tyre. Blessed with two harbors and the love of far-away Carthage, Tyre was a threat to Alexander’s supply lines as he prepared to conquer the Persian Empire. From Tyre, the beleaguered Persians could land behind Alexander’s forces and isolate them from Greece, or they could sail to Greece and sponsor an uprising against Alexander with the restless Athenians.

Tyre was well fortified, and the city-state included a walled island off the coast. Determined to eliminate the threat, Alexander built a causeway from the coast to bombard the island with artillery. Tyre responded by converting old boats into fireships that were rammed into the artillery, destroying it all. Committed to taking the island, Alexander assembled a navy from Tyre’s Phoenician rivals as well as from the Cypriots and several Greek cities in Ionia. After six months of exhaustive siegecraft, Alexander was able to breach the walls of Tyre and storm the fortress island. 6,000 defenders were killed in the storm, 2,000 locals were crucified afterwards, and what was left of the population was sold into slavery.

The threat of the Persian navy eliminated, Alexander marched south to take Egypt. The fortress at Gaza under the command of the eunuch Batis remained loyal to the Persians, and blocked Alexander’s path to Egypt. Batis hoped that he could hold out against Alexander to give Darius enough time to raise a new army and lift the siege. Batis’ hopes were misplaced, and Alexander stormed the fortress successfully on his fourth attempt. The men of Gaza were exterminated, and the women and children were sold into slavery.

Alexander’s destructive path down the Levantine coast was not unprecedented, even among Greeks. Over 800 years before, other Greeks had laid waste to the Levant, known only to their adversaries as the mysterious “Sea Peoples”. Since the rediscovery and decipherment of Bronze Age texts in the 19th century the identity of the Sea Peoples has remained undetermined until now. New work in archaeology and genetics has positively identified at least some of them, and given new insights into their world.

The peoples of Greece past and present have been linked to the Middle East more closely than any of the other peoples of Europe. Their ancestry, their culture, and their history have deep links, far deeper than is commonly understood.

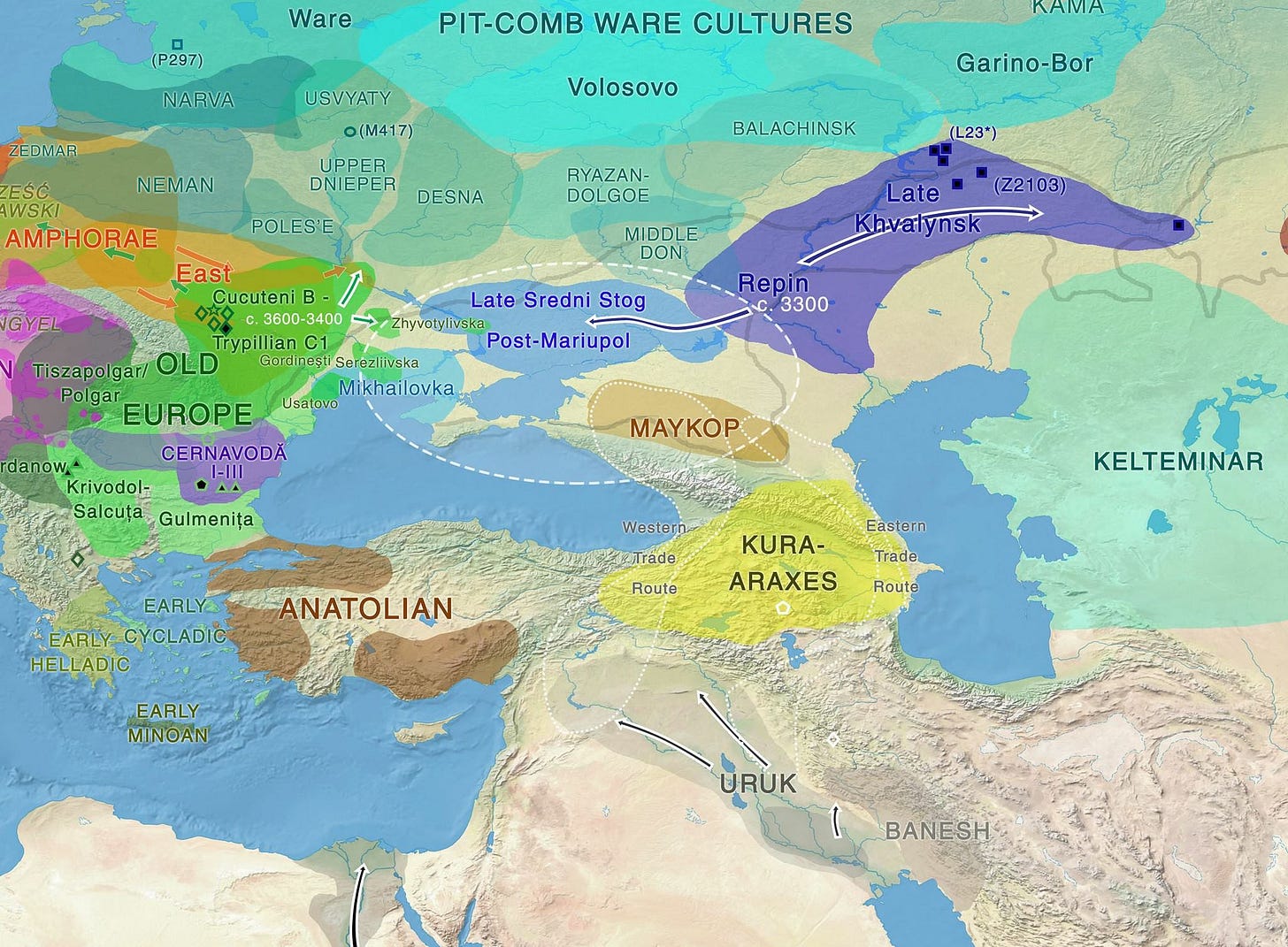

Greece was the first part of Europe colonized by the Early European Farmers, migrants from Anatolia (Asiatic Turkey) who introduced farming to the continent. The Early European Farmers, or EEFs, colonized Crete by 7000 BC, mainland Greece by 6700 BC, and Macedonia by 6500 BC. From there, they spread across the Europe. One branch of EEFs migrated by land into Hungary, Ukraine, Romania, and Germany. The other branch migrated by the coast into Italy, southern France, Iberia, and finally North Africa. As they expanded, the EEFs encountered other races, among them the primitive Western Hunter-Gatherers (WHGs) and the Eastern Hunter-Gatherers (EHGs) .

By the mid to late 5th millennium, the peoples of Greece had diverged from their cousins. Europe was convulsed in a parallel set of conflicts involving tribes of WHGs conquering their EEF neighbors and establishing themselves as a new ruling class, catalyzing a new synthetic culture with their new subjects. Greece was one of the few regions of Europe spared that particular conflict (Croatia was another), and was instead affected by the changes in Anatolia.

Even before those 5th millennium convulsions, Greece had followed a different path. As early as the 58th century BC, there are signs of further migrants from Anatolia settling in Greece and the southern Balkans. These migrants bore both the familiar ancestry of the Early European Farmers as well as genetically distinctive ancestry of the Caucasian Hunter-Gatherers (CHGs). The migrants were the products of a complex process of migration and mixing that was taking place over much of the Middle East at the time.

As the populations of 5th millennium BC Anatolia and Greece were mostly descended from the EEFs, even small shifts detected in their CHG ancestry fraction would imply substantial population replacements because the possible sources of CHG ancestry were already quite diluted. There is some evidence for how such shifts may have occurred.

Alepotrypa cave is an archaeological site from around 3800 BC in the Peloponnesus. More than a tenth of the skeletons show that healed skull fractures. Further north in Thessaly, the site at Sesklo was a walled settlement destroyed by fire around 4400 BC, after which it was abandoned.

While those specific sites are unlikely to represent population changing migrations, they do give a picture for the violence of the era. There is no reason to believe that invaders from across the Aegean Sea would have been any kinder.

The 33rd century BC was a time of great upheaval even by the standards of prehistory. New fortifications were erected all over the Balkans, and were paralleled with the depopulation of numerous archaeological sites. The invention of multi-oared longboats allowed for trade routes to connect the peoples of the Eastern Mediterranean and the Black Sea more closely than ever. North Caucasian pots, Egyptian glaze, Baltic amber, Crimean carved stone stelae, and undoubtedly much more crossed the seas.

Improvements in seafaring did not only bring about more trade. The 33rd century saw a sudden increase in the amount of CHG ancestry found in the peoples of Greece, three new archaeological cultures, and the introduction of bronze. Invaders, possibly from the Black Sea coast of northern Anatolia, replaced a significant part of the population.

These invaders included the famous Minoans of Crete, as well as the less well known but ancestrally (and probably linguistically) similar Cycladic and Early Helladic peoples. There are hints that there may have been multiple waves of invaders from Anatolia, leaving at least Crete a linguistically fragmented island. Reigning for at least 900 years, the Cycladics, Early Helladics, and Minoans remained in close contact with each other. Evidence of trade between the islands, mainland Greece, western Anatolia, and Crete are abundant for that era.

While the Minoans and their cousins enjoyed the bounties of Aegean Sea, titanic events shaped the rest of the Europe. Around 3000 BC, a group of savage tribes now known as the Indo-Europeans invaded Europe from eastern Ukraine and southern Russia, destroying the EEF civilizations east of the Rhine in at most two centuries. Not content with their new lands, the Indo-Europeans learned how to build boats and launched a new wave of bloody conquests 350-600 years later.

Two branches of the second Indo-European wave play a role in this story. The first was was the early Greeks themselves, who arrived in northern Greece (Macedonia and Thessaly) at the end of the 3rd millennium BC. The other was the Sicanians, who settled the Balearic Islands and conquered Sicily between 2400 and 2200 BC. While the language of Sicanians is unknown, their ruling class was at least initially Indo-European in origin.

The 23rd and 22nd centuries BC were another era of cataclysm, featuring the falls of entire civilizations and great wanderings of peoples across the world. Historical climate data shows a general trend of aridification, which would have inflicted famines upon agricultural societies. Tax revenues would have declined and the political order fell apart. As far north as the Arctic the ancestors of the Saami (Lapps) and Yukaghirs waged pitiless wars against their neighbors. In Karnataka in southern India pastoral herders overran the native farmer society, torching their settlements. Egypt fell into a dark age called the First Intermediate Period that lasted 126 years. The mysterious Gutians overthrew the mighty men of Akkad in modern-day Iraq. In the Yangtze River Basin, the Liangzhu Civilization collapsed.

Greece was not spared that merciless period. As far south as the Peloponnese archaeological sites were destroyed. On their ruins, structures and artifacts such as tumuli burial mounds and shaft hole axes characteristic of Indo-European peoples (of whom the Greeks came from) were found.

Ancient DNA finds from the Elati-Logkas site in western Macedonia confirm the identity of the invaders. The earliest known Greeks are found in this site, and despite several centuries of time separating them from the initial conquest, they were quite distinctive from their predecessors. About 2/5ths of their ancestry came from the original Indo-Europeans. Even more of their ancestry came from the subjects of the Indo-Europeans further north, who by the time of the invasion had mixed considerably with their conquerors.

Thucydides writes that the Greeks of the centuries before the Trojan War had no conception of national identity. Instead, they identified with their tribes, some of them named in Homer’s epic poem “The Iliad”. Many of these tribes worked as pirates, sailing around the seas and pillaging unguarded villages that they found. Some of the Greeks continued that lifestyle into Thucydides own time, though piracy was undoubtedly interrupted by periods in which a regional naval hegemon secured the sea lanes.

Greek pirates took more than plunder from their pirate voyages. The Mycenaean city of Pylos has writings referencing women from western Anatolia, possibly slaves. Sexual slavery in southeastern Europe continued off and on well into the Middle Ages. The peoples of the modern Balkans have much of their Slavic ancestry not through Slavic invaders in the Dark Ages, but rather Slavic women slaves taken in the Middle Ages.

The Minoans survived the late third millennium period of cataclysms, with their island of Crete remaining in their hands for another seven centuries. Minoan civilization was robust enough to survive even the eruption of a volcano on the island of Thera and a related tsunami in the 17th century BC. Some Minoan sites have layers over the Thera eruption related ash layer, confirming that they did indeed survive the second period of cataclysms.

Nonetheless, Minoan civilization was not to last. Mycenaean Greeks from the mainland invaded Crete around 1450 BC, and set themselves up as the new rulers. Contemporary Egyptian records from the tomb of Pharaoh Thutmose III’s vizier Rekhmire reference visitors who ruled Crete as well “Islands in the Midst of the Sea”, likely the Cycladic Islands of Greece. Other Egyptian records reference Cretan ships and their construction and maintenance.

Thucydides, writing in the 5th century BC, also references a powerful historical ruler in Crete - Minos. He writes that Minos was first ruler in the Aegean to build a powerful navy, and used his navy to conquer the Cycladic Islands, end piracy, and allow for the expansion of trade. With piracy gone, the people on the coasts began to settle cities, consolidate their polities, and build walls. New settlements were built on the Aegean coast of Anatolia as well, including Miletus.

Thucydides’ description of an expansion of trade and developed settlements in the Aegean is supported by archaeology. The 15th and 14th century Aegean saw the construction of numerous palaces as well as the erection of Cyclopean walls (thought by the later Greeks to be the creation of the mythical cyclopes). Greek pottery and artifacts were found as far east as Mesopotamia (modern day Iraq) in this period. Linear B, the earliest examples of Greek writing, also date starting from the period.

To the west, Sicily had been ruled by an Indo-European derived group originating in Iberia since at least 2200 BC by the time of the Mycenaean Greek expansion. Thucydides called these Indo-Europeans the Sicanians, and states that they came from the Jucar River Basin (modern Cuenca, Albacete and Valencia). The Sicanians still controlled part of western Sicily as late as the 5th century BC. The practiced agriculture and bronze working, and preferred trading to the east rather than the west. They built their settlements in the open, indicated that warfare was sparing rather than intensive.

This changed in the 17th century BC. The Mycenaean Greeks invaded Sicily and made it their first overseas conquest. The island’s population shrank dramatically, and settlements were built in defensible areas. Mycenaean architecture and pottery replaced the old styles, and Mycenaean Greeks settled the land. Trade was oriented even more to the Aegean Sea and the world of the Mycenaean Greeks, though pottery from the Apennine Mountains in Italy has also been found. The changes to Sicily were not only architectural and economic, but genetic as well. The Mycenaean Greeks settled the island with their Minoan and Minoan-like subjects.

During their conquests abroad, the Mycenaean Greeks back home mixed in with their subjects. By the time the time of Bronze Age Collapse of around 1200 BC, the Greeks had perhaps a twentieth of their ancestry from the original Indo-Europeans of the steppe, and two-thirds of their ancestry came from their Minoan and Minoan-like predecessors. This ancestry composition likely remained the norm for Greeks deep into the Classical Era, if sample I8215 of the the 5th century BC Greek colony of Empuries in Iberia is any indication. Modern Greeks may have as little as half their ancestry from the Classical Greeks, although some estimates put it at over two-thirds.

The Mycenaean Greek conquests and expansion abroad left them with at least a few enemies, some very powerful. The Hittites, based in central Anatolia, enforced a trade embargo against the Greeks. Very few Greek artifacts are found in the Hittite sites of this era, and very few Hittite sites are found in Greek settlements. This embargo lasted for at least three centuries, from the fifteenth to thirteenth centuries.

What sparked this embargo will likely remain shrouded in mystery. What is known is that after the fall of Crete to the Mycenaeans, the Hittites crushed a rebellion of a group called the Assuwa in western Anatolia around 1430 BC. The Assuwa included the people of the city now known as Troy - Wilusiya - remembered by Homer as “Ilios”. The Assuwa had some contact with the Mycenaeans. Hittite texts reference Mycenaeans in reference to the Assuwa, and a Mycenaean sword was found in Hittite territory referencing the rebellion. From the Greek records, a reference in the Iliad to Hercules sacking Troy may be a dim memory of this old conflict fought long before the Trojan War.

A treaty signed around 1225 BC between the Hittites and their allies in coastal Syria banned trade with “Ahhiyawa” - a word related to “Achaea” - the land of the Achaeans referenced in the Iliad.

Trade embargos could greatly hurt the economy and revenues of a state. While finances of the late Bronze Age eastern Mediterranean will never be determined, the extent of trade was vast. Lapis lazuli from Afghanistan, amber from the Baltic, and tin from Britain all made their way to the eastern Mediterranean. One shipwreck from around 1300 BC carried enough metal to outfit three hundred soldiers with a full set of bronze armor and weapons.

Records from the Classical Era show how important trade was to the revenues of a state. 1st century BC Rome obtained a third of her state revenues from the customs of her international trade, mostly done by sea through the Red Sea and Indian Ocean. This may have been even greater for realms such as Mycenaean Greece, which would have found tax collection difficult in the rocky terrain of Greece. While Mycenaean Greek records are sparse, many Greek records from that period reference the sea involve the recruitment of oarsmen - sailing was very labor intensive, and oarsmen would have always been needed.

Even today, sea transport is cheaper than land transport. In the Bronze and Classical Ages the advantage of sea transport was even more extreme. There was no need for the construction of roads and tens of tons could be transported long distances. Travel times by sea were considerably less than those on land, and armies could be resupplied far away. Bronze Age states with strong navies would have a tremendous advantage over their rivals.

Sea power was undoubtedly the decisive factor in the success of the Greeks in their late Bronze Age expansion. A campaign such as the Trojan War could never have taken place without Greek naval supremacy, nor could Greek colonies have been established in Sicily, Crete, and the Levant without it. Sea power would also enable the greatest Greek expansion prior to Alexander: the conquests of the Sea Peoples.

One group of the Sea Peoples is well known - the Philistines. Having failed to conquer Egypt in two invasions in 1207 and 1177 BC, they instead returned to what they had previously conquered in what is now modern day Israel. Identified in the Bible as originating from Crete, the Philistines proceeded to settle down and intermarry with the locals. DNA testing of Philistine remains has confirmed their Mycenaean Greek origins. One Philistine woman who was DNA tested appears to be pure Mycenaean in ancestry.

The Philistines (known to the Egyptians as the Peleset) were among several groups listed as the Sea Peoples by the Egyptians. The other Sea Peoples were the Tjekker, the Shekelesh, the Ekwesh, the Shardana, the Danuna, and the Weshesh. An inscription on the tomb of Ramses III reads:

“The foreign countries made a conspiracy in their islands. All at once the lands were removed and scattered in the fray. No land could stand before their arms, from Khatte, Qode, Carchemish, Arzawa, and Alashiya on, being cut off at [one time]. A camp [was set up] in one place in Amurru. They desolated its people, and its land was like that which has never come into being. They were coming forward toward Egypt, while the flame was prepared before them. Their confederation was the Peleset, Tjekker, Shekelesh, Danuna, and Weshesh, lands united. They laid their hands upon the lands as far as the circuit of the earth, their hearts confident and trusting.”

Arzawa is in western Anatolia, Khatte is the Hittite realm in central Anatolia, Qode is Cilicia in modern southeastern Turkey, Carchemish was a city on the banks of the Euphrates River, Amurru was an Egyptian vassal in northern Lebanon and coastal Syria, and Alashiya is Cyprus. The Danuna are the Greek tribe of Danaans referenced by Homer in “The Iliad”. The ruins of the Hittite capital of Hattusa have been excavated, and the destruction of the city was between 1190 and 1180 BC. In the same decade, the city of Troy was destroyed as well, likely in what is remembered as the Trojan War.

The identity of the other groups is less certain. The Mycenaean Greeks are known to have had contact with the EEF peoples of Sardinia - the Nuragics - from pottery finds. The etymology of Sardinia’s name is unknown, but the the name predates the arrival of the Phoenicians. The Shardana referenced by the Egyptians as being among the Sea Peoples may be Sardinians, Nuragics recruited by Mycenaean Greek sailors for campaigns of plunder and conquest. The Sardinians certainly knew of the wealth of the east - their copper, valuable in the Bronze Age as one of the ingredients for bronze, originated from Cyprus.

Similarly, the name of the Shekelesh may refer to the aforementioned Sicanians in Sicily. Alternatively, it could refer to the Italic-speaking Sicels (relatives of the Romans) who invaded southern Italy and Sicily in the late 13th or early 12th century during a massive drought in their home, the Po River Basin of northern Italy.

The path of destruction the Egyptians describe is far from complete. In addition to the places in Anatolia referenced in Ramses’ tomb, archaeologists have uncovered numerous sites in the Levant (modern Lebanon, Israel, and Syria) which were destroyed. The great port city of Ugarit, near modern Latakia in Syria, was sacked in the decade preceding the Sea Peoples 1177 BC invasion of Egypt. It was not the only Levantine city sacked in that decade.

The devastation reached Greece itself, as numerous cities were destroyed or abandoned. Two terrible droughts devastated the eastern Mediterranean and Ethiopia 1250-1150 BC and 1100-850 BC. Genetic finds from the Greek colony of Empuries in the 1st millennium BC support a continuity of the late Mycenaean Greek to Classical Greek ancestry composition, so if there was an invasion of non-Greeks, it had little lasting effect. More likely, a collapse in trade and a series of bad harvests drove the Greeks to expand abroad. After meeting defeat at the hands of the Egyptians, they turned on themselves, fighting for what little food and farmland was left.

Thucydides describes a period of revolutions in Greece after the Trojan War that forced the exile of many men. The Boeotians were driven out of Thessaly and into Boeotia by the Thessalians, while further south the Peloponnese was conquered by the Dorians and Heraclids. Homer describes vicious feuds between returning Trojan War veterans and Greeks back home as well. Some of the veterans won the feuds - Odysseus slaughters the suitors of his wife Penelope with their lovers in The Odyssey. Other times the veterans were defeated. Agamemnon was assassinated by his unfaithful wife’s lover Aegisthus, who is in turn killed by Agamemnon’s son Orestes years later.

The Mycenaean Greek colony in Sicily collapsed after its motherland. Thucydides, in his history, makes no mention of Greeks in Sicily prior to the Phoenicians, and after 1000 BC. Invading Italic-speaking Sicels from Italy may have destroyed them, or the Sicanians overthrew them. By the time the Greeks colonized the island again, the memory of their predecessors who had ruled parts of the island for centuries had been forgotten.

The Philistine colonists in modern day Israel lasted longer. They continued to make their pots the way their Greek ancestors had made them, although with local clays. They left little ancestry in the blood of their successors. It is possible that they were always a small group, and intermarried extensively with the locals, their blood diluted over the centuries. It is also possible that as a military ruling caste they bore the brunt of fighting in a dark age of drought and barbarism, only dimly remembered in the Bible. Alternatively, they may have spent too much of their time in disease ridden cities, reproducing at a lower rate than the healthier countryside. The finally disappear from history after the destruction of their realm by Babylon in the 6th century BC.

After the terrible droughts that caused the Bronze Age Collapse finally ended in 850 BC, the Greeks resumed their seaborne colonization of the Mediterranean, following the same winds that their Minoan and Mycenaean ancestors had. Their need to hold their 227 islands required shipping and sea power, giving them a great advantage over the land based powers such as Persia, enabling such unlikely victories as Salamis. It gave Athens the ability to ship armies across the sea to Sicily, as well as grain from Crimea to feed the city even in famine. The sea power would enable Alexander and his successors to dominate the eastern Mediterranean for centuries, until the cousins of the Sicels, the Romans, finally overcame them in a repetition of history.

When the Romans passed, the Greek-speaking eastern half of the Roman Empire, Byzantium, became the dominant sea power in the eastern Mediterranean for centuries more. Defying the Arabs, Turks, Slavs, and others successfully for centuries in part due to their naval power, Byzantium was finally crippled by yet another group of Italians - the Venetians leading the Fourth Crusade.

Since independence in the 19th century and again driven by their geography, the Greeks have again become a sea people. They lead the world in shipping tonnage, with over 300 million tons capable of being carried by over 5,000 Greek-owned vessels. This is the life of the Greeks, and has been their life for over 5,000 years.

Sources:

1) https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.aav4040

2) https://www.motya.info/text/6102/en

3)https://www.oxfordhandbooks.com/view/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199572861.001.0001/oxfordhb-9780199572861-e-36

4) https://www.worldhistory.org/article/1190/bronze-age-sicily/

5) https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-020-14523-6

6) https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/584714v1.full

7) https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.aax0061

8) https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0092867421003706

9) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Helladic_chronology

10) “The Horse, the Wheel, and the Language” by David Anthony

11) “First Farmers of Europe” by Stephen Shennan

12) “1177 BC: The Year Civilization Collapsed” by Eric Cline

13) “The Roman Empire and the Silk Roads” by Raoul McLaughlin

14) http://oaktrust.library.tamu.edu/bitstream/handle/1969.1/ETD-TAMU-2009-12-7643/CHOLTCO-THESIS.pdf?sequence=2&isAllowed=y

Some others that I’ve forgotten or may have hallucinated

Books cited in spirit but not in fact for the naval theme:

“The Influence of Sea Power upon the French Revolution and Empire, 1793–1812” by Alfred Thayer Mahan

“The Napoleonic Wars: A Global History” by Alexander Mikaberidze

Twitter users that provided invaluable information for this article:

https://twitter.com/CandideIII

https://twitter.com/ByzLevant

https://twitter.com/cartographer_s

Brilliant piece. Nemets is a pioneer.

Very interesting article, thanks!