"You sing of the young gods easily

In the days when you are young;

But I go smelling yew and sods,

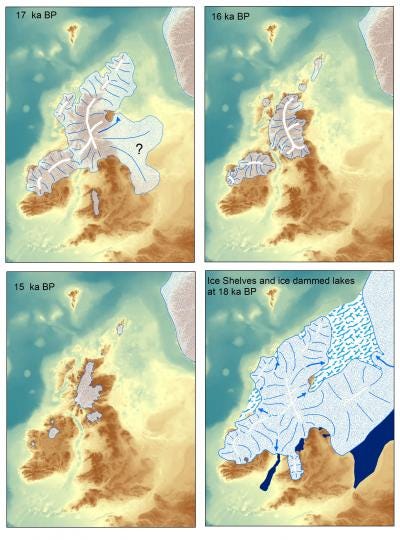

The Magdalenian hunter-gatherers noticed that the winters were not as bitter and the summers not as short as they had been in the days of their distant ancestors. The reindeer were migrating to the northwest - to a strange land of which the Magdalenians were only dimly aware. Some of the Magdalenians decided to follow. It was around 13,500 BC when they crossed the Doggerland land bridge from continental Europe to what is now England.

The Magdalenians ruled what is now southern England for the next thousand or two years. Their lives were nasty, brutish, and short. They hunted land mammals across southern England - including each other. Finds of human bones from the Magdalenian era of British prehistory show evidence of both nutritional and ritual cannibalism. They used the skulls of their victims as drinking cups.

As the climate continued to warm, the cultural toolkit of the Magdalenians became increasingly inferior to the encroaching Western Hunter-Gatherers. Expanding out of Italy and the Balkans, the Western Hunter-Gatherers (WHGs) largely destroyed the Magdalenians outside of Iberia. Britain was no exception. In the 12th millennium BC the WHGs crossed the Doggerland land bridge into Britain and exterminated the Magdalenians there in totality. The world at the time was cold, harsh, and primitive. There was no food surplus for slaves, so the defeated were invariably slain. Only further south in the lush lands around the Mediterranean could one hope for any sort of mercy.

While Britain remained connected by Doggerland to the European continent until the 7th millennium, Ireland had been separated from Britain for thousands of years. It was not until around 8000 BC - over 3,000 years after the WHGs had arrived on Britain - that they sailed to colonize Ireland and the Isle of Man.

While the WHGs of Britain remained in contact with their WHG cousins on the continent, the WHGs of Ireland fell into total or near total isolation. As a result, the WHG material culture in Ireland quickly diverged from their cousins to the east and south. Ireland could support few hunter-gatherers, thus the population of the WHGs there fluctuated between 3,000 and 10,000 people. While primitive by our standards, they were nonetheless capable of remembering extensive family trees. They were able to avoid the worst forms of inbreeding even though their prolonged isolation and small population size likely caused an unusually high number of genetic diseases.

The late 7th millennium BC - perhaps the 63rd century specifically, featured a number of cataclysms around the world. Rising sea levels caused by rising temperatures had already turned Doggerland into the Dogger Archipelago. The collapse of part of the continental shelf off of the coast of Norway triggered at least one massive tsunami that drowned much of what remained of Doggerland as well as flooding Britain as far as 42 kilometers inland. The Danube River severely flooded around the same time. Those catastrophes devastated the WHG populations of Europe, and opened up the continent to colonization by farmers from Anatolia - what is now the Asian part of Turkey.

Those Early European Farmers (EEFs) split into two groups early on. The first, the Linear Ceramics (green and olive in the map below), gradually expanded up the Danube Basin into Hungary, Austria, and finally Germany. The second, the Cardial Wares (blue and cyan), followed a coastal route along the Adriatic in the western Balkans into Italy, southern France, and finally Iberia. Those two groups collided in France and began mixing (presumably through both peaceful and violent exchanges) at the end of the 6th millennium. While the EEFs brought both crops and domesticated animals with them from Anatolia, they were not able to colonize all of Europe. Hills, forests, and most of the northern European coastline were beyond their ability to settle. The soils were not good enough to sustain their colonists in the face of the neighboring WHG fishermen or foresters. Britain too remained in the hands of the WHGs.

Following a peak at the end of the 6th millennium BC, the EEFs entered a centuries-long period of decline. While their gods had never been kindly, they appear to have been cast out by crueler deities around that time. Like the Nahuas 6,500 years in the future, the EEFs warred for human bodies to satiate their appetites for flesh and the appetites of their gods for sacrifices. The EEFs stagnated across Europe until the 45th century.

The introduction of copper metallurgy in the Balkans in the mid-5th millennium BC was shortly followed by the shattering of the weak EEF order across Europe around 4400 BC. WHGs overran EEFs across most of Europe, installing themselves as the new rulers over the sedentary EEF populations. The WHG rulers synthesized their material culture with that of their EEF subjects, creating new cultures whose people were still largely of EEF ancestry. Those new synthetic cultures were able to exploit a broader range of ecologies than either the WHGs or original EEFs. They fished, hunted, gathered, herded, and farmed. As a result, they were able to gather enough food to allow their population to grow internally while also allowing for external colonization.

While the Channel Islands had been colonized by EEFs from Brittany in the mid-5th millennium BC, large scale EEF colonization of Britain and Ireland wouldn’t begin for another several centuries. Previous EEF attempts to colonize at least Ireland had failed. The apparent creation of sizable chiefdoms in what is now France towards of the end of the 5th millennium finally allowed for colonization. Apparent conquests to the south in the preceding two centuries were not able to satiate the growing population’s needs for arable land by the 43rd century BC. As a result, the chiefdoms in France or groups within them eventually launched a sizable colonization program in the 41st century.

Such a colonization program can be seen in the DNA of the farmers who settled Britain. Had the farmers been from small and isolated groups, then they would have been noticeably more inbred than they actually were.

One of the chiefdoms in France was based out of Brittany, which by the late 5th millennium had the state capacity to build large monuments. It colonized parts of Normandy in France as well as southwestern England, Ireland, and northern Scotland. The other chiefdom was in the Paris Basin in northeastern France and colonized England from the southeast before pushing north and west. As both chiefdoms were probably founded by different groups of WHG conquerors, their colonies in Britain likely differed in both in language and ruler.

Colonization brought with it new diseases that affected the flora and fauna of the British Isles. It may be that the WHGs were overrun so swiftly in part because of EEF diseases spread by men, pigs, or cattle. At the very least elm trees were devastated, speeding the clearing of the land for agriculture.

Some groups of WHGs in the British Isles managed to endure for a time. Shell middens, a sign of fishing settlements typical of WHGs, are found in western Scotland and the islands off the coast of Scotland even centuries after EEF settlement. Nonetheless, the EEFs fully colonized the British Isles within three centuries. Armed with axes imported from the Alps as well as those manufactured from flint mined in southern England, the EEFs swept the scattered WHGs aside. The EEF settlers could grow many times more calories in the form of crops or domesticated animals than the WHGs could gather from fish or game in the same land. Thus the EEFs multiplied and expanded, while the WHGs retreated and were overcome.

The surviving WHGs were absorbed into the EEF population to varying degrees depending on region. Few if any WHGs were absorbed by the EEFs who settled Wales, implying at least one instance near-total extermination in the region in the early 4th millennium. The colder climate of Scotland as well as its maritime resources allowed for the WHGs there to be relatively populous enough to contribute around 10% of the ancestry of later EEFs in the region. In the north, a WHG fisherman could somewhat compete with an EEF farmer.

While the WHG-EEF synthesis in the 45th century had been brutal, the succeeding eight centuries were largely an EEF golden age. Society, culture, architecture, and technology all advanced in tandem with continent-wide population growth. The British Isles were no exception, reaching their peak in the 37th century. The density of cereal pollen in samples taken around the British Isles support a population peak and extensive cereal cultivation at that time. In addition, the archaeological record suggests that housing construction was at its highest in Ireland in the same century.

EEF societies around Europe began to decline around the 37th century. Some argue that the decline was caused by a gradual climate change that cooled Europe and increased rainfall in the British Isles. Others argue that the first of many plagues swept across Eurasia. Still others believe it was part of a natural civilization cycle, with decreasing yields from agriculture due to soil exhaustion. Regardless of the cause, the decline shows in the archaeological records of the British Isles.

The EEFs of the British Isles showed signs of decline a century before - in the 38th century BC. Whatever political authorities ruled the islands had begun to disintegrate, perhaps due to a climate or plague induced decline in tribute. Locals began building what archaeologists call causewayed enclosures - essentially kraals that sheltered men and livestock behind concentric ditches and palisades that were bridged by an earthen causeway. The peak of the causewayed enclosure construction was in the 37th century, although construction continued through the 36th until almost ceasing in the 35th. The causewayed enclosures were largely abandoned by the 33rd century.

The causewayed enclosures were built at great expense because they were needed. The neolithic decline in Europe was violent even by the standards of prehistory - even if not as violent as the early 5th-millennium or mid-3rd millennium. Some 4-8% of skulls found from the era showed signs of violence. Some places like Hambledon Hill were directly attacked, with the skeletons of battle casualties still on site.

The endemic warfare that characterized the 3600-3200 period coincided with economic shifts. Wheat was replaced by the more robust crop barley, and wild plants appear more often in EEF sites in the British Isles. Archaeological sites from that period are scarcer than the era before. Trade of carinated bowls and axes broke down. Mines closed. All in all, the picture of the 3600-3200 BC period across the British Isles is one of decline and a decrease in population.

The islands off of the coast of Scotland were an exception to the general trend of decline. Unlike the rest of the British Isles, those islands didn’t experience a population decline in the 4th millennium. A new archaeological culture called the Grooved Ware, named after their distinctive style of pottery, originated in the Orkney Islands north of Scotland around 3200 BC. Grooved Ware pottery as well as architectural designs previously found on Orkney rapidly spread around the coasts of Ireland and Britain. Due to the conservatism of prehistoric pottery makers, the spread of such pottery suggests the spread of power, influence, and people as well.

The spread of such influence - likely that of a thalassocracy based in the Orkney Islands - came either because or at the expense of the peoples of the rest of the British Isles. The EEFs in Britain and Ireland who had already shifted from wheat to barley cultivation increasingly gave up on agriculture altogether after the 34th century. Large parts of the isles were depopulated and seem to have fallen into a period of savagery which lasted 900 years. Wild bands of cattle herders and hazelnut gatherers eked out a precarious living in the interior while Grooved Ware sailors from the Orkney Islands thalassocracy and its colonies reaved the coasts.

My suspicion is that the spread of the wheel and the sail in around the Eastern Mediterranean and Black Sea in the mid-to-late 4th millennium enabled the faster spread of diseases around the early Bronze Age world, devastating all peoples. Many states collapsed entirely, but some - like the Orkney Islands thalassocracy and the unifiers of Egypt - managed to endure and emerge even stronger.

The thalassocracy and its colonies built numerous monuments to their rulers in imitation of their trading partners and possible coreligionists in Brittany and other places on the Atlantic coast of Europe. One of those monuments was a tomb in the Boyne Valley of east-central Ireland. The tomb appears to be that of a king claiming rule through divine blood as the man buried within was the product of first-degree incest - a practice later embraced by Egypt and Iran in a form of cultural convergence.

Elsewhere, concentrations of burial monuments and the relationships of the men buried within them suggest that late 4th millennium society in the British Isles - or at least Ireland - was clan based. Grooved Ware-associated monuments and centers remained close to waterways, but were usually a moderate distance inland. Presumably that enabled easy access to water if needed, but also bought time to muster reinforcements in case of a sea raid.

Far to the east, the great and terrible Indo-Europeans were rising on the Pontic steppe in what is now Ukraine and southern Russia. Led by a mighty warlord in the 30th century BC, they overran Europe north of the Danube and east of the Rhine over the course of the next two centuries. That series of invasions ended the long-decaying EEF societies of northern Europe. Primitive people by the standards of their neighbors, the Indo-Europeans turned farmlands to pastures and extinguished anything recognizable as civilization.

Able to sail the Baltic from early on in the 3rd millennium BC, the Indo-Europeans may be the cause of the decline of the Orkney Islands thalassocracy in the 29th century and after. Historical thalassocracies and even traditional land empires relied heavily on sea trade for state revenue, and the Orkney Islands thalassocracy was likely no different. By losing control of the North Sea trade routes, they perhaps lost their wealth and eventually control of their colonies. The earliest evidence for Indo-European sea reavers operating west of Denmark is in the 27th century.

The Bell Beaker culture originated in Iberia early in the 3rd millennium, and spread across the Mediterranean before it moved up the Balkans into the Indo-European lands north of the Danube. There, the Bell Beaker culture was adopted by an unusually violent subgroup of Indo-Europeans originating in the lower Rhine and Ems river basins (modern Netherlands and northern Germany) which had invaded the northern Balkans in the mid-3rd millennium.

The Indo-Europeans of the lower Rhine and Ems basins perhaps learned more advanced shipbuilding technology from the more technologically advanced populations of the Mediterranean. Boat finds in the Bell Beaker era of Britain in the late 3rd millennium suggest that boats were an important aspect of society and greatly valued by the wealthy.

With their advanced ships, the Indo-Europeans of the Rhine and the Ems sailed across the North Sea to invade the British Isles in the 25th century. Their invasion was near-genocidal, with 90+% population replacement in the succeeding centuries. It also introduced the Bell Beaker culture to Britain.

While the Bell Beakers were a violent people, they restored some order in the isles. Pollen samples from the second half of the 3rd millennium show renewed agricultural cultivation across much of England, with even marginal lands exploited. They preferred less productive but more robust barley over wheat, so while the population grew it didn’t surpass the peak of the 37th century. They opened up mines - but for copper rather than flint. Ross Island off of the coast of southwestern Ireland supplied most of the copper in the British Isles for centuries. The Bronze Age was almost a thousand years old by the time that metalworking was introduced to the isles by the Bell Beakers, even if it wasn’t until 2200 BC that true bronze was forged from both copper and tin. Gold was mined extensively in Ireland, and exported to both Britain and France.

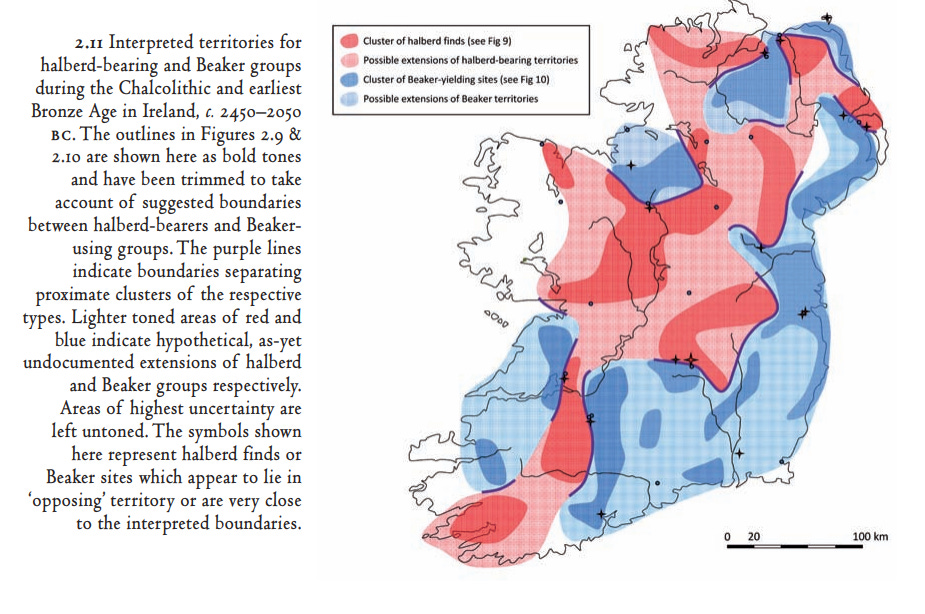

The Bell Beaker Indo-Europeans were resisted by the EEFs for centuries in the British Isles. Stuart Needham has suggested that the EEFs of Europe’s Atlantic fringe from Iberia to Ireland shared a sophisticated technique of copper halberd manufacture in the mid-3rd millennium. He points out that finds of those halberds rarely coincide with the Bell Beakers that characterize the Indo-European invaders, who preferred metal daggers for weapons at the time.

His theory is unlikely as the local EEFs had no tradition of metallurgy and the isles had been underpopulated for centuries. In addition, none of the post-Bell Beaker samples in Britain which have been DNA tested so far show more than 50% EEF ancestry. The more likely explanation is the Bell Beaker invaders came in waves, with the earliest waves mixing in with some of the EEFs before being overcome by later waves which further diluted the EEF share of ancestry. Earlier waves of Bell Beakers may have abandoned the older style of pottery for local styles, much as they did with local houses.

However, there are two signs that point out to at least some coexistence between the EEFs and Bell Beakers. The first is Irish mythology and folklore, which in various forms records the EEFs as introducing farming and building the large passage tombs. Indeed, it even recalls that builders of the passage tombs practiced incest. Such myths and folklore were probably passed down from the EEFs to their Bell Beaker conquerors.

The other sign is on the Orkney Islands. While the power of the old thalassocracy had been broken centuries before the Indo-European invasions of the isles, the ruling families managed to maintain their position. Their direct male line descendants remained the predominant element in the Orkneys even a thousand years after the invasion - a time when Indo-European lineages had almost entirely swept the others away. It is possible that they even maintained their non-Indo-European language (an ancestor of Pictish?). However, the people of the Orkneys by that point were largely indistinguishable from their southern neighbors. Centuries of intermarriage had blended them together, bringing the Orkneys into the Indo-European world as equals rather than as slaves.

The British Isles thrived for about 900 years under the Indo-Europeans after the conquests. The broad range of manufacturing in Ireland in the latter half of the 2nd millennium suggests that Ireland was wealthier and more densely populated than England. However, the descendants of the Bell Beakers were not to reign in the British Isles forever. The world was still centered around the Middle East and the Eastern Mediterranean. Events there shaped the distant lands of the British Isles too.

The volcanic eruption at the island of Thera in the 16th century BC may have triggered a period of mass migration. Regardless of the cause, there was a substantial invasion from Scandinavia and continental Europe in the following century which overran much of southern and eastern England. The invasions altered the demographics of southern England - and social order - noticeably. Scotland and Ireland were spared the invasion or successfully repelled it - at least for the next five centuries.

The results of the invasions and fighting around 1500 BC changed the funerary customs in southern England as well as its trade routes. Graves in England are more equal in size and quality of burial goods for the 1500-1000 BC period, suggesting the fall of the old warlords and the rise of tribal assemblies. Bronze ceased to be made in England, but was instead imported from the continent. Horses were introduced by the invaders for the first time. England’s trade shifted towards the North Sea, while Ireland’s remained oriented towards the Atlantic coast.

That world too was ephemeral. The climate shift at the end of the 2nd millennium BC caused widespread famines across Eurasia. The resulting Bronze Age Collapse devastated civilization and drove a number of wanderings of peoples from Ethiopia to the Baltic. It afflicted the British Isles too.

Breakdown in trade cut the supply of metals needed for tools and weapons while crop yields fell. War ensued across the isles. While hillforts had appeared in Ireland centuries earlier, many more were built - and burned - during the Bronze Age Collapse of 1200-800 BC. There is no place in Europe with a higher density of bronze weapon finds from that era than Ireland. The warfare ended in the total collapse of the social and political structures in Ireland.

It wasn’t until late in the 1st millennium BC a thousand years later that the people of Ireland advanced beyond basic subsistence agriculture and pastoralism again. Only then would its population begin to recover.

In England, foreign invaders again sailed across the Channel and North Sea with fire and sword. Unlike their predecessors earlier in the millennium, they would have a more lasting legacy. Likely speaking the proto-Goidelic Celtic languages (ancestral to Gaelic and Irish), they faced of stiff resistance. Hundreds of ringworks were built around England and Wales during the Bronze Age Collapse - undoubtedly to hold off invaders. They were largely built in futility - the Celts replaced about half of the population of England and southern Wales. Western Scotland, Ireland, and northern Wales largely held off the Celtic invaders - perhaps allowing for the survival of Bell Beaker Indo-European or even EEF non-Indo-European languages into the Iron Age and beyond. In time, they ended up adopting the Goidelic languages anyways - perhaps under the influence of a relatively small Goidelic Celtic ruling or priestly class which left only a minor (but detectable - about 20%) genetic impact.

When civilization began to recover from the Bronze Age Collapse with the spread of ironworking in the 9th century, the face of Britain had changed. East Anglia and the Midlands appear to have been relatively peaceful by the standards of prehistory. They were protected by a fortified frontier of hillforts that fenced off what is now Wales, Cornwall, and the Scottish Highlands. The relatively egalitarian ethos that had characterized England since the 16th century invasion appears to have endured - with little distinctions between status in graves.

Britain would remain troubled by invasions into the Iron Age. Proto-Brittonic speakers riding chariots invaded Yorkshire in northeastern England from what is now western Germany and northeastern France in the 4th century BC. Either they, their influence, their imitation, or processes driven in reaction to them appear to have led to an end of the long egalitarian period of English prehistory. Warrior burials and sculptures that follow their arrival suggest the rise of a professional warrior class which replaced tribal militias of freemen. They also introduced La Tene culture art from the continent. It survived longer in Britain than it did on the continent.

It may be that the Romans ruled Britain for longer than the Britons did. If the Arras culture were indeed the speakers of proto-Brittonic, then they would have ruled parts of Britain for at most 450 years, or perhaps as little as 300. The Romans by contrast ruled Britain from 43 to 410 AD - 367 years.

The Romans became a diverse and cosmopolitan empire following the devastation of Italy during the Second Punic War. People from northern Europe, east Africa, and more than anything the eastern Mediterranean migrated across the empire - in many cases largely replacing the local urban populations. Britain was no exception - receiving substantial numbers of migrants from places both within the empire such as Syria and outside of the empire such as west Africa.

The Crisis of the Third Century AD permanently weakened the Roman Empire and devastated its diverse urban populations who were more vulnerable to epidemics. Rural peoples from the countryside began to move into the cities to replenish the legions and the dying urban populations. DNA results from a limited number of Roman military burials in Britain suggest that most legionaries towards the end of the empire were locals - but that some were foreigners from Germany and Syria as well.

Subsequent barbarian invasions largely finished off what was left of the diverse imperial urban populations in Europe - including in Britain. The Anglo-Saxons followed the paths of at least four preceding groups of conquerors across the North Sea and made their mark in blood and on history.

The Anglo-Saxons invaded England from the continent’s North Sea coast in the 5th and 6th century. They brought with them a Germanic language - Old English. The invasion was part of a mass migration that brought substantial numbers of women and children. How substantial is debated - the noticeable genetic impact of the Anglo-Saxons isn’t necessarily from a genocidal series of conflicts. While the invasions were certainly violent, the Anglo-Saxon replacement of perhaps a third of the population of England could have been due to relatively higher fertility and lower mortality rates. Their impact on Ireland and Scotland was at most minor.

Germanic cousins of the Anglo-Saxons, the Vikings, reaved the North Sea rim from the late 8th to mid-11th centuries AD. Despite initial successes, battlefield defeats and massacres ensured that Viking influence on Britain would remain restricted to the periphery. The old heartland of the Orkney Islands thalassocracy as well as Shetland became Viking colonies which spoke a Norse language into the 19th century.

After the Anglo-Saxons, there was one last great successful conqueror. William of Normandy led an army of Normans, Flemings, and Bretons to overthrow the Anglo-Saxon ruling elites. William and his men were few in number, and like the Viking raiders left little of a genetic impact on the British Isles.

Medieval economic development - particularly watermills - allowed for England to finance the armies and navies that it needed to preserve order at home and its independence abroad. The Anarchy, the Wars of the Roses, and the Wars of the Three Kingdoms were quite bad by historical standards, but minor by prehistorical standards. Society didn’t collapse in entirety in any of those cases as it had in prehistory, so the population remained high enough to avoid replacement.

In conclusion, the British Isles have experienced at least five major episodes (it is undergoing a sixth) of population replacement and four episodes of civilizational collapse.

Summary:

13,500-11,500 BC Magdalenians

11,500-4000 BC WHGs

4000-2400 BC EEFs (collapses around 3300 BC and 2400 BC)

2400-1000 BC Bell Beakers & descendants (Goidelic invasions around 1500 BC and 1000 BC, collapse around 1200 BC)

1000 BC-500 AD Celts (Brittonic invasion around 400 BC, collapse in 410 AD)

500-2060 AD Anglo-Saxons

2060-???? AD UKians

Another very interesting article. Even for a Historian, it shows just how far back we can go (usually British history starts around the time of the Roman invasion with a few words about Celts). Civilisation is a cyclical phenomenon, that waxes and wanes with the times. Those who believe in a "End of History" type of world view - regardless of political orientation (Marxist or Fukuyamist) are dreamers, not realists.

an outstanding read. thanks