Rajah. Rex. Reich. Ruler. Similar words relating to a position of power or an area where such a position’s power is exercised. Oddly, those words are from languages spoken quite far from each other in time and place. Rex was the title of the kings of Rome prior to the rise of the Republic. Rajah was a title in India for centuries, Reich the German word for realm, and ruler an English word.

Such similarities between the languages of Europe and the languages of India were noticed as far back as the 16th century, when merchant Filippo Sassetti noticed that the Sanskrit words for snake, seven, eight, and nine were similar to those of Italian. In the latter half of the 18th century, linguists gradually came to realize that Sanskrit was related - however distantly - not just to Italian, but also to Russian, Persian, Greek, Latin, German, and the Celtic languages.

Linguists and archaeologists in the 19th and 20th centuries slowly developed a theory of a proto-Indo-European language - a language spoken in the distant past that was the ancestor of the Indo-Aryan, Iranian, Germanic, Slavic, Albanian, Armenian, Greek, Hittite, Celtic, and Italic languages. Due to the huge number of speakers of the proto-Indo-European’s daughter languages, the origins and spreads of Indo-European attracted a great deal of interest.

Advances in technology as well as new finds in the late 20th and early 21st centuries - particularly advances in ancient DNA extraction and analysis - have tremendously illuminated prehistory, including for the earliest Indo-European peoples. It is now possible to tell their story in at least the broadest of outlines.

The Indo-Europeans of the late 5th millennium BC were a primitive and marginal people. They predominately dwelled between the Don River and the mid-to-lower reaches of the Volga. They fished and hunted along the cold river, living short and violent lives. Their home was flat, part of the great Eurasian steppe which stretches from Hungary in the west to Manchuria in the east. There was no political unity on the steppe, with numerous races extant and extinct reigning in their own limited ecological niches, only occasionally bursting forth in an age of conquest.

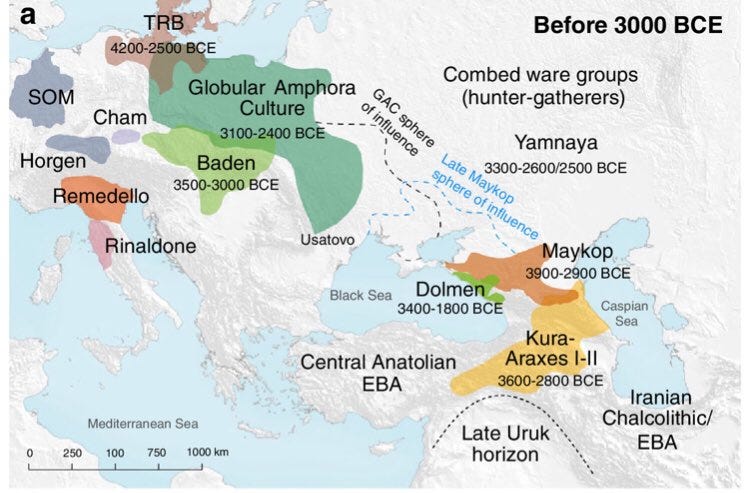

To the north reigned the Eastern Hunter-Gatherer tribes, who in the preceding centuries had invaded the Baltic during the great wanderings of peoples around western Eurasia around 4400 BC. While the Indo-Europeans shared about half of their ancestry with the Eastern-Hunter-Gatherers, they also shared ancestry with peoples to their south in the Caucasus Mountains. Some of that ancestry was old - from fishermen and seal hunters who had migrated up the western coast of the Caspian Sea to the Volga Delta near what is today the city of Astrahan. Some of that ancestry was newer - from Middle Eastern farmers who had mixed with the peoples of Anatolia and the Caucasus before in turn mixing with the Indo-Europeans in the middle of the 5th millennium BC some centuries prior. In spite of kinship some twenty generations before, the peoples of the north Caucasus and the steppe were at least sometimes at odds - the former building thickly-walled settlements to protect themselves from invaders from the north and south.

To the west reigned the mighty and wealthy men of the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture. One of the cultures formed from the great hunter-gatherer and farmer synthesis of mid-5th millennium BC Europe, the Cucuteni-Trypillians nonetheless thrived in the latter half of the 5th millennium in what is now Moldova, northern Romania, and western Ukraine. While a settled people, they supplemented their diets with hunted animals. They were connected by trade to the seashell traders of the Aegean, the copper miners of the Balkans, and the peoples of the North Caucasus.

To the east were mysterious peoples with little if any legacy today. Fishermen around the Caspian and in the Amu Darya basin, big game hunters in what is now northern Kazakhstan, and a myriad of tribes in Siberia. Their contacts with the Indo-Europeans were presumably hostile. Across the millennia, there appears to have been no sign of intermarriage. Such hostility was the norm in primitive societies. In the Americas, the Amerindians and Na Dene often knew their neighbors only by exonyms such as “enemies”.

The first apparent invasion of noticeable impact by the Indo-Europeans took place in the last two centuries of the 5th millennium. Perhaps speaking a language ancestral to the most divergent branch of Indo-European, Hittite, the men who formed the Suvorovo Culture (range in picture below) stormed into the coastal plain of the eastern Balkans with fire and mace. Judging from the skulls of them and their descendants of the Cernavoda Culture, they had a substantial demographic impact.

How they conquered the eastern Balkans is unknown. The arrival of the Suvorovo culture is associated with carvings of horses - an animal important to the Indo-Europeans in southern Russia and eastern Ukraine, but not the people of the Balkans. Perhaps they rode horses bareback to settlements for raiding, then dismounted for fighting. Or perhaps they were mere infantry taking advantage of chaos within the eastern Balkans. Regardless, the invasion was destructive. The Black Sea coastal plain in the eastern Balkans was so devastated that it was only inhabited by migratory pastoralists for at least the next seven centuries - until 3300 BC.

The Cucuteni-Trypillians to their northwest responded to the arrival of the Indo-Europeans by concentrating their settlements, expanding arrow production, and building fortifications. Half of known Cucuteni-Trypillian fortified sites and 60% of projectile points are from the 4300-4000 BC period that coincided with the arrival of the likely Indo-European Suvorovo culture. There was no increase in the share of wild animals finds, strongly suggesting that the arrows were used for war rather than hunting.

The Cucuteni-Trypillian efforts to stave off the rude Indo-European invaders from the east were successful - for a time. While Indo-European ancestry within the Cucuteni-Trypillians increased over the course of the fourth millennium BC, it is notable that no Cucuteni-Trypillian men tested thus far have been the male line descendants of Indo-Europeans. Indeed, the Cucuteni-Trypillian sample that had the greatest share of Indo-European ancestry was a deeply malnourished child - perhaps a slave. The would be Indo-European conquerors from the east were conquered in their journey to the west. Civilization had endured.

The next two noticeable migrations of Indo-Europeans out of their homeland in the western steppe occurred around 3300-3200 BC. One traveled all the way to central Mongolia, and the other followed the path of the Suvorovo culture and invaded the Black Sea coastal plain in the eastern Balkans. Unlike the Suvorovo invasion, the reasons for the second Indo-Europeans expansion of ~3300 BC are better understood.

While the Indo-Europeans had possibly ridden horses for a thousand years by the 34th century BC, their lifestyle remained closely tied to hunting and gathering. They hunted deer and fished for food, which forced them to stay near rivers. The wide expanses of grass that covered the steppe for eight thousand kilometers could sustain cows and horses, but not men.

In the mid-to-late 4th millennium BC, that lifestyle changed. The Indo-Europeans adopted dairying. Dairying had been known to the peoples of the Middle East and Europe for thousands of years, but it was generally a supplement to agriculture. After all, a farmer could get ten to twenty times as many calories from farming land as he could from having animals graze it. Thus it was only the marginal lands of the farmers which were grazed. The cold lands of the steppe were hostile to the crop package of farmers in the 4th millennium - it was not until the Middle Ages that winter-resistant strains of rye were developed.

With the Indo-European adoption of dairying, the steppe had ceased to be a wasteland. It became a pasture capable of sustaining the Indo-Europeans through their herds of goats, horses, sheep, and cattle. While they could not drink the milk of their animals (evolution for lactase persistence occurred 2,000+ years later, mostly in the later Bronze and Iron Ages), they could still obtain the milk’s calories and nutrients as cheese, yogurt, or fermented liquids.

The result was a population boom. With more food and more land, the Indo-Europeans became healthier and more of their children survived to adulthood. If their population growth reached 3% per year (about the maximum record population growth rate in history), their population may have been doubling as little as every quarter century. If it grew by 2% per year, it would have been doubling around every 35 years. Even if it grew by 1% per year - perhaps kept low by vicious internal feuds relating to cattle raiding - it would have still doubled every 70 years. Even a 1% annual increase in population would have resulted in the Indo-European population multiplying by twenty by the time of third wave of Indo-European conquests 3000-2900 BC.

The second wave of Indo-European expansion was launched within a few decades of the dairy-driven population boom. In the west, the Usatovo culture was formed around 3300-3200 BC by a materially-minded group of Indo-Europeans perhaps desiring to seize control of the river trade routes that connected Central Europe with the Black Sea. All six of their known settlements overlook what would have been good harbors in the late 4th millennium BC on the coastal plain of the northwestern Black Sea. The time was a tumultuous one, but one of rapid economic growth. The Usatovo conquerors were contemporaries of the unifiers of Egypt as well as the the Minoans who invaded Greece from northern Anatolia. Bronzeworking, carts, and sailboats were revolutionizing society and expanding trade - trade which the Usatovo clearly took part in.

The Usatovo may have pushed the descendants of the Suvorovo and the ancestors of the Hittites from the eastern Balkans into Anatolia, thereby spreading proto-Hittite into the regions just to the west of its historically recorded range. An admittedly low DNA coverage late 4th millennium BC woman in northwestern Anatolia, what would become the famous Troad of Trojan War fame, shows signs of Indo-European ancestry. While turmoil and interaction between northern Anatolia, Ionia, Thrace, and Greece is evident from archaeology; a multidisciplinary approach that includes ancient DNA is needed to better understand the Aegean and Bosporus 3300-3000 BC.

To the east, the Afanasievo culture (location on map below) was formed from Indo-European migrants genetically identical to the much more famous people of the Yamnaya culture. Riding across the steppe, with some apparent detours in Central Asia, the Afanasievo culture established itself in Tuva, Dzungaria, Khakassia, and the western half of Mongolia. They brought their animal herds with them to the eastern steppe, introducing pastoralism to the region for the first time.

The Afanaseivo Indo-Europeans were not as destructive as later Indo-European groups. The ecology they exploited - the steppe - was relatively unpopulated, so they were able to settle it with little bloodshed. Their legacy appears to be threefold: first the introduction of pastoralism and copper metallurgy to the eastern steppe, second the spread of an Indo-European language (pre-proto-Tocharian), and third the connection of the disease pools of eastern and western Eurasia.

The Tocharian languages are known historically from a number of documents dating to the mid-1st millennium AD in the Tarim Basin, what is now the southern part of the Chinese province of Xinjiang. The second most divergent branch of the Indo-European language family, it is likely that they descend from a shared proto-language spoken by the Afanasievo people - even though the historically-known speakers had no ancestry from the Afanasievo people. The Afanasievo people engaged in contact with a number of peoples in Siberia, the Altai, the Minusinsk Basin, Dzungaria, and Mongolia. Indeed, it appears that the Afanasievo were absorbed or overthrown by those peoples within a few centuries of their arrival in the east. It is possible that the greater mobility of the Afanasievo people caused by their horses and carts led to their language became a trade language of the earliest predecessors of the Silk Road. In time, most of the Tocharian languages were swept away by the waves of Iranian, Turkic, Uralic, Yeniseian, Mongolian, and Sinitic speakers; leaving just the isolated peoples of the Tarim speaking the old trade tongue.

The new connections between east and west that were opened by the Afanasievo Indo-Europeans may have brought something devastating - plague. In the ages before the horse, the wheel, and the sail; travel was slow and expensive. Diseases caused illness and death, but their reach was shorter and spread slower. Indeed, there are suggestions that most genetic selection for disease resistance occurred not with the rise of agriculture and growth of settled populations, but during and after the 3rd millennium BC with improvements in transportation and the growth of international trade.

The oldest known strains of plague diverged in the 38th century BC, and had spread to Europe by the 30th century BC at the latest. The effect may have been devastating on the unprepared populations. The Cucuteni-Trypillians may have burned their settlements every few decades in hopes of expunging plague while the Funnelbeaker people of northern Europe and Hamin Mangha died in droves at the time of its spread. The Afanasievo may have been peaceful for their time, but it is possible that their efforts at trade wrought death on a scale unmatched by any contemporary warlord.

Those deaths may have opened up Europe to the third wave of the Indo-European expansions. The 3000-2800 BC period saw a massive series of invasions of Eastern and Central Europe from the steppe which resulted in dramatic demographic and cultural shifts. None could stand against the Indo-European armies of mounted infantry. The largest set of those invasions is associated with the Corded Ware culture. About 75% of the ancestry of the Corded Ware people came from the original steppe people between the Don and the Volga - the same population that generated the Yamnaya and the Afanasievo, as well as probably the earlier Usatovo and Suvorovo. The remaining 25% was from farmers and hunter-gatherers in the southern Baltic and Poland.

The Corded Ware largely ended civilization north of the Danube for the next six centuries. They burned forests, turned farms into pastures, and wiped out settlements. Entire peoples were exterminated in their conquests. The Scandinavian Hunter-Gatherers who survived the invasions of the Indo-Europeans fled to the far north, enduring for a few more centuries on at least the island of Tromsoya before they were overrun by the Saami. Further to the east, the Indo-Europeans overran the Eastern Hunter-Gatherers of the Volga and Kama basins, destroying them or forcing them to flee to the far north as well. Only where the cold was too bitter for cattle could the enemies of the Corded Ware truly be safe.

Further south, the Yamnaya branch of Indo-Europeans followed the path of the Suvorovo and Usatovo peoples - overrunning the Black Sea coastal plain of the eastern Balkans as well as penetrating into Hungary and Croatia. One early 3rd millennium BC woman, from Slavonia in modern Croatia, appears to be the product of a direct mixing between the Yamnaya Indo-Europeans and the unique locals, suggesting that Yamnaya bands in the Balkans mixed with their neighbors in parallel rather than in series. The Yamnaya penetrations into Hungary and the Balkans in the early 3rd millennium BC were ephemeral. While they may have left a small genetic impact on their successors, it was later migrants from the Middle Bronze Age whose legacy is more obviously apparent. The more populous and sophisticated peoples of southeastern Europe proved more capable of resisting the Indo-European invasions than their distant northern cousins.

The Maykop culture of the north Caucasus suddenly disappeared around 3000 BC, its advances and achievements forgotten. A biracial society, the ethnic core of Maykop in the south was rooted from south Caucasian settlers who had pushed away their predecessors - distant relatives of the Indo-Europeans - earlier in the 4th millennium BC. To their north was Steppe Maykop - people related to the peoples of Central Asia and western Siberia, perhaps invited to settle the steppe between Maykop and the Indo-Europeans. While such a relationship proved beneficial for a time (Maykop sites are mostly unfortified and show little signs of violence), the Indo-Europeans of the 30th century destroyed both in entirety. It was an episode of the eternal struggle between the peoples of the steppe and the peoples of the Caucasus, one that has been repeated time and time again even into the 20th century.

Interestingly, a Y chromosomal haplogroup (R1a-M417) associated with the Indo-Europeans diversified rapidly during the Bronze Age, suggesting a wide spread from a small number of men. It is likely that the Indo-Europeans, whose men initially mostly carried R1b lineages, were led by a clan or even a single Chingis Khan-tier figure who were/was able to unite the feuding steppe tribes into a powerful all-conquering horde around 3000 BC. Their/his descendants retained considerable power and prestige over the centuries, enabling the spread of their lineage.

What could have allowed them to gain such power? Was it mere chance, skill at diplomacy, success at war, or a charismatic religious vision? Perhaps, but it may have been material. Around 3000 BC, the Yamnaya Indo-Europeans stumbled upon a copper mine in the southern Urals. While not able to exploit it to its full potential, they did nonetheless mine it, enabling them to make copper axes and other useful tools and prestige goods. For a warlord, there is no more important task than to arm one’s warriors with the finest weapons, so the progenitor of the R1a lineage may have been the owner of that mine. With men better outfitted than their rivals, the R1a progenitor - perhaps remember in the future as the Sky Father, Dyeus Phaeter - could have triumphed again and again in battle, unifying the tribes and embarking on the great third wave of Indo-European conquests.

The Indo-European conquests halted for the centuries following 2800 BC. Depopulated frontiers between the Corded Ware people in Europe and their civilized neighbors to the south suggest enduring hostile relations for a time. Trade died.

The mid-3rd millennium saw the spread of the Bell Beaker culture from Iberia across Europe. A heterogenous culture embraced by multiple races and states, the wealth that it spread proved to drive the fourth expansion of the Indo-Europeans. Barley begins to be found in Indo-European parts of Europe, and thus suggests an increase in the Indo-European population. More calories can be generated per unit of land by agriculture than by herding. The Indo-Europeans of continental Europe mixed a bit with their neighbors and surviving subjects during their adoption of the Bell Beaker toolkit. As a result, the amount of original steppe Indo-European ancestry in them fell from 70% (the original Corded Ware) to about 45% in southern Germany and Poland (it remained closer to 70% in northern Germany, the Low Countries, Scandinavia, and the steppe itself).

Sailing on boats of unsurpassed design in the continent, the Indo-Europeans seized the sea routes in the North Sea and Bay of Biscay possibly as early as the 27th century. With the population boom in the 25th century, they renewed their invasions. The fourth wave of Indo-European invasions saw the near-extermination of the peoples of Britain and Ireland, with over 90% population turnover. Only in the Orkney Islands to the north of Scotland did the pre-Indo-European peoples endure, eventually assimilating into the new order on their own terms rather than those of the Indo-Europeans. The more densely populated peoples of France also suffered severely from the Indo-Europeans, although population turnover was less - perhaps 40-50%. About 45% of the ancestry of the post-invasion people of northern France was of the original steppe Indo-Europeans, and about 25% of the ancestry of the post-invasion people of southern France was of the original steppe Indo-Europeans.

Following the conquest of France, the Indo-Europeans continued to drive south. Lowland Galicia was largely depopulated, with the survivors fleeing to higher ground - perhaps due to Indo-European piracy on the coasts. Most settlements in Cantabria were abandoned, suggesting that the Indo-European invaders there displaced their predecessors. In Portugal, lowland sites may have been taken by the Indo-Europeans, but their predecessors held out in hill settlements in the east. Southwestern Iberia saw most of its settlements abandoned around 2500 BC. While southwestern Iberia did see the establishment of a number of new settlements afterwards, human activity remained considerably lower for the next thousand years, strongly suggesting that the Indo-Europeans devastated the region during their arrival and reduced much farmland into pasture.

Heterogeneity in the archaeology of Iberia in the latter half of the 3rd millennium BC suggests that the Indo-European expansion into the peninsula wasn’t as straightforward as it had been in northern Europe. The preceding peoples likely endured in the south-central parts of Iberia, as well as in isolated holdouts in the interior. Notably, the Roman geographer Strabo discusses the Turdetani people of southern Iberia, and how their historical memory dates back some 6,000 years. It had been about 5,600 years since the Early European Farmers (EEFs) had settled southern Iberia; so it is plausible that a surviving population which had endured the Indo-European, Carthaginian, and Roman conquests would remember so far back.

In the north of Iberia, some Indo-Europeans were successfully absorbed into political structures that led to the new conquerors adopting the Basque language even as they largely extinguished the male lineages of their predecessors. In the southeast of Iberia, the Indo-Europeans established themselves as the new ruling class, changing the lifestyle and depopulating the region while mixing with with the distinctive locals who likely had affinities to the Minoans and other peoples of the northeastern Mediterranean. About 20% of the ancestry of the people sampled in northern and eastern Iberia after the invasion is from the original steppe Indo-Europeans - half that of the peoples of France, and less than a third of that of the Corded Ware. Indo-European ancestry was diluted as it spread further away.

Not halting at the Mediterranean, the Indo-Europeans sailed from Iberia into North Africa at some point, the Balearic Islands around 2400 BC, and Sicily by 2200 BC. The sea invasions of the islands of the western Mediterranean were done prior to the completion of the conquest of Iberia, and DNA samples from the Balearic Islands show heterogeny in ancestry. It seems that the relatively more Indo-European descended warrior class kept its position for a few centuries, prior to being fully absorbed into the neighboring population.

While the Indo-Europeans also invaded Sardinia, the locals managed to successfully repel them. They retreated to the highlands, and gradually pushed the invaders into the sea. Even today, there is little Indo-European ancestry in Sardinia. They are the closest living relatives to the Early European Farmers who ruled most of Europe from 4400-3000 BC (the EEFs before 4400 BC had less Western Hunter-Gatherer ancestry than those after).

Momentous movements were going on in the other parts of the Indo-European world around 2500 BC as well. The ancestors of the Slavs, Aryans, and Iranians destroyed the other Indo-Europeans in the western steppe homeland. The survivors fled west and south.

The refugees who fled west reached what is now Macedonia and northern Greece by 2200 BC. There, they mixed with the locals, with about 30-40% of their ancestry deriving from the steppe and the remainder from the locals and other peoples of the Balkans. They would remain in northern Greece for centuries, held off by the Minoans and their cousins on mainland Greece to the south until the 18th and 17th centuries.

The refugees who fled south crossed the Caucasus and came into contact with the Kura-Araxes people. In a series of terrible wars, the Indo-Europeans largely depopulated the south Caucasus and violently ended the Kura-Araxes culture. Forests replaced fields, and a new cultural synthesis of the steppe and Kura-Araxes people formed. Important people were buried in large mounds just like those of the Indo-Europeans on the steppe, but the pottery was made in the same manner and style as it had been by the Kura-Araxes. It appears that a horse-riding Armenian ruling class associated with the Bedeni and Martkopi cultures ruled over a number (though not all) of the peoples who lived exploiting the diverse ecologies of the south Caucasus. While there was a degree of initial mixing, perhaps with allies, in the initial decades of the conquest, the Armenian ruling class didn’t intermarry much with its subjects or neighbors until the end of the Bronze Age. About a third of their ancestry remained from the original Indo-Europeans of the steppe until then.

The Sintashta Culture was an eastern descendent of the Corded Ware Indo-Europeans, and is believed to be the ancestors of the Aryans and the Iranians - the proto-Indo-Iranians. Ingenious engineers, they built well-organized fortifications as well as war chariots - both of which enabled them to thrive during the aftermath of the climate induced civilizational collapse of 2200 BC. They were also skilled horse-breeders, developing the lineages which predominate in horses today.

The Sintashta and their descendants invaded Central Asia in a complicated series of invasions that went back and forth. One group of Indo-Iranians invaded central Mongolia from the central steppe, mixed with the locals, then invaded the Altai and mixed with the locals there. Other Indo-Iranians invaded the Zeravshan River basin in what is now Tajikistan and eastern Uzbekistan, depopulating the region and seizing its tin mines around 2000 BC. Over the course of the 2nd millennium BC, the Indo-Iranian invasions of Central Asia appear to have replaced around 50-60% of the population.

To the west, the Greeks finally overran the Minoans and their mainland cousins from 1700-1500 BC, establishing the Mycenaeans. The history of the Greeks in the 2nd millennium is somewhat known - considerably better than most contemporary peoples. The predecessors of the Greeks clearly played a major role in Greek society, with some of the richest tombs from the Mycenaean period showing no Indo-European ancestry. The Greek takeover of Greece was probably the gradual growth of an alliance network - Thucydides suggests as much, and also specifically states that the alliance network grew out of Thessaly. Genetics supports that the Mycenaeans and the Classical Greeks were around 10% steppe Indo-European (Yamnaya) in ancestry, which goes well with that theory. The Greeks who had lived in the north from 2200-1700 accounted for perhaps a quarter of the resulting Mycenaean synthesis in the last third of the Bronze Age.

Also in the 1700-1500 BC period, the Indo-Iranians pressed into Siberia, influencing the ancestors of the Uralic peoples. The Uralics, armed with superior weapons forged from their mines, viewed the Indo-Iranians as inferiors. Their word for slave was “orya” - clearly derived from the Indo-Iranian endonym “arya”. The chariots that gave the Indo-Iranians such an advantage in Central Asia and Mongolia proved useless in the swamps and forests of Siberia.

Those chariots would be useful in the Middle East. The Kingdom of Mitanni in what is now northeastern Syria was taken over by a group of Aryans (the Aryans are a branch of the Indo-Iranians, *not* the ancestors of the Germans) who set themselves up as the ruling class in the 16th century BC. Bearing names similar to those of later Indian rulers, Mitanni offers, along with comparative Uralic mythology, the earliest evidence for what evolved into Hinduism.

While Indo-European groups from the north had invaded northern Italy by 2000 BC, there were apparently a number of successive Indo-European invasions into Italy in the 2nd millennium BC as well. Much as wave of Celtic, German, and Iranian invaders moved from the north into the sunny lands of Italy during Roman times, so too did other Indo-Europeans try to take peninsula in the Bronze Age. It may be that the obscured memories of the earliest Romans are due to the confusion of such migrations, with part of their ancestry deriving from Central European groups who crossed the Alps southwards during the Bronze Age Collapse.

It was the Bronze Age Collapse 1200-800 BC that marks the final end of the prehistoric Indo-European expansions. The Iranians poured into Iran, becoming the Medes, the Persians, and others. The Aryans had prodded at the fringes of the Indian subcontinent for centuries, but with their enemies weakened by famine and long decay, they were finally able to sweep into the Indo-Gangetic Plain. In the eastern Mediterranean, the Mycenaean Greeks and their allies laid a path that Alexander would follow and surpass centuries later. The Iron, Classical, Middle, and Modern Ages would see more historical expansions and retreats, all of which are out of the scope of this post.

While there is evidence for the Indo-Europeans maintaining ties of kinship and sharing identities across wide geographical expanses early on in their expansion, those faded with time. Indeed, given extensive intermarriage with neighboring and subject peoples as well as linguistic diversification, many Indo-European groups would have and indeed did see each other as alien. This article should *not* be read as an attempt at anachronistically imply unity to groups of peoples who clearly and repeatedly engaged in internecine conflicts. It should be read as an attempt to summarize how the ancestry and languages associated with a small collection of tribes in the steppe region that now encompasses eastern Ukraine and southern Russia came to spread to places as far apart as Ireland, Mongolia, Syria, and Bangladesh.

In addition to link articles, the sources for this post are:

The Horse, the Wheel, and the Language by David Anthony

First Farmers of Europe by Stephen Shennan

Empires of the Silk Road by Christopher Beckwith

The Archaeology of the Iberian Peninsula by Katina Lillios

The Urals and Western Siberia in the Bronze and Iron Ages by Lyudmila Koryakova and Andrey Epimahov

The Archaeology of the Caucasus by Antonio Sagona

The Landmark Thucydides by Richard Crawley

The Prehistory of Britain and Ireland by Richard Bradley

I wonder who would win in a fight between the R1a-M417 Ur-father (Dyḗus ph₂tḗr) and the Germanic I-M253 Ur-father (Wātónos)

An excellent article Nemets. It is truly amazing how much we have been able to piece together of ancient pre-history thanks to modern science.

A question for you. If we look at language spoken around the world, it is clear that that Indo-European has been the most successful in spreading its influence judging by the amount of people speaking it. However if we look at DNA, are the Indo-Europeans the most successful or does some other group take that title?