Civilization is old - at least 11,700 years old - and has risen and fallen at least six times. Each of those falls was an apocalypse in the biblical sense. Cities were destroyed or abandoned, productive lands were turned into deserts, cultural sophistication regressed to primitive artisanry, barbarian warlords overthrew law, and human populations fell dramatically. The Fall of Rome was one of those apocalypses, with western Eurasian civilization only barely hanging on in Constantinople under the Byzantines and in the Levant under the Umayyads.

Interspersed between the apocalypses such as the Fall of Rome and the Bronze Age Collapse are eras of crisis. In those crises, civilization bends but it does not break. There is war, disease, and devastation; but political authority is restored and the world order is renewed - even if diminished. The last such crisis that our species experienced was in the mid-17th century during the Little Ice Age. The Thirty Years War in Germany, the Deluge in Poland, the Ruin in Ukraine, and the Manchu Conquest of China in East Asia all occurred in a very narrow time frame, and were driven by broader centuries-long climactic pressures as much as by local political disputes. Authorities across the world were confronted with the same problem: the cold was killing their crops, and their people were starving. They could go forth to conquer like Prince Dorgon or Bogdan Hmelnitsky to secure food for their people. Alternatively, they could try to endure the vicious internal struggles that arose from the desperate masses of starving peasants.

One era of crisis was that following the 23rd century BC (possible that it began as early as the 2240s or as late as the 2180s) - in the middle of what is now known as the Bronze Age. A shift in global climate patterns that lasted about three centuries shook most of the world. Some parts of the world cooled and rainfall patterns changed. Some regions experienced an increase in rainfall along with an increase in flooding. Other areas saw prolonged droughts which caused famines. A fall in temperatures slew the beasts upon which man relied on for food, transportation, and manure.

Any of those changes alone would have shaken any contemporary sedentary society to its foundations. Farmers faced starvation from bad harvests. Tax collectors and lords found it difficult to extract the usual amounts of wealth from the farmers - and they feared the potential of peasant rebellions. Kings struggled to pay for their courts, bureaucracies, and most dangerously armies due to falls in tax revenue. Across the world stages were set for revolutions, civil war, barbarian invasions, and the collapse of civilization.

The world just before the crisis of the 23rd century BC would have been alien to us in the present not only in its customs, languages, and traditions - but also in its racial distribution. The races we are familiar with today were generally far less widespread in the 3rd millennium - if they had even been born at all. Conversely, numerous races that are now extinct or marginal once ruled large parts of the earth.

What we would today call the White race1 - the mixture of the proto-Indo-Europeans from the Pontic Steppe with the Early European Farmers (EEFs) who preceded them in central Europe - only dominated in northern, central, and eastern Europe prior to the Crisis of the 23rd Century. The EEFs still dominated southern Europe in Iberia, Italy, and parts of the Balkans. The Minoans and closely related peoples who had strong affinities to the populations of northern Anatolia ruled Greece.

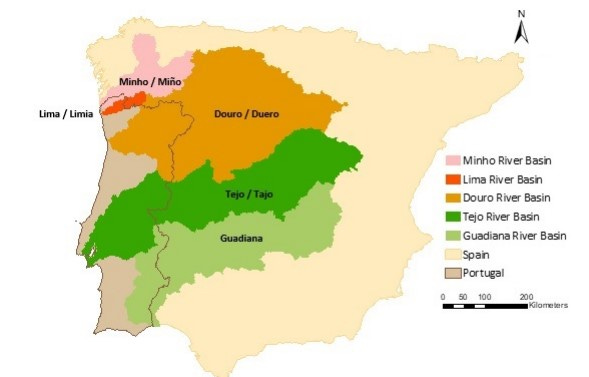

While Indo-European derived populations had penetrated parts of northern Spain as early as the 24th century2, most of the Iberian peninsula remained outside of their control prior to the 23rd century. The EEFs of Iberia were considerably denser in population than their cousins who had been overrun earlier in the millennium in central Europe. Their larger population plus greater technological sophistication and access to copper enabled them to better resist outside invaders. The EEFs in Extremadura and the Douro River Basin built extensive fortifications to resist their enemies. Southern Iberian archaeological sites in particular, such as the Ubeda in the Guadalquivir River Valley, demonstrate that the region’s EEFs had populous societies capable of mobilizing resources on a large scale. Nonetheless, the archaeological record suggests that the struggle between the EEFs and the northern invaders was a grim struggle. Northeastern Spain was largely depopulated between 2400 and 2200 BC, indicating endemic warfare between the Indo-Europeans and Iberian EEFs in the region.

The Guadalquivir River Basin

The partly Indo-European derived populations of northern Spain would be the main actors in the Iberian peninsula’s 23rd century BC drama. Increases in rainfall in northwestern regions such as Zamora dramatically decreased the salinity of local soils. Climate instability undoubtedly undermined the fabric of the local society. The northerners had a choice - brave out changing conditions, or follow the example of their ancestors and march south to conquer. Biological signs of human habitation almost entirely disappear, showing that they decided to march south. Their intention was to conquer or die rather than eke out a marginal existence on increasingly poor soil.

Southern Iberia was a rich region even when it was in decline. The hotter, drier summers and colder, wetter winters brought by the 23rd century caused a retreat of the EEFs up the Guadalquivir from the southwest to the northeast. There, they continued to fell forests for fuel and pollute the water with heavy metal runoff from their copper industry. Correctly identifying the northerners as an existential threat, they erected extensive fortifications.

The EEF efforts were largely - but not entirely - a failure. Numerous towns were stormed and burned. Most settlements were depopulated. Large scale migration of northerners to the south replaced perhaps 40% of the population, with the invading men slaughtering most of the local men and taking their women. Almost all male lineages were replaced by the R1b lineage common in Indo-Europeans. However, there appear to have been some EEF holdouts in parts of Andalusia and the Tagus River Basin. Those holdouts would in time enter into the new order on their own terms, rather than that of the northern invaders. The descendants of one of those holdouts may have even maintained their historical memory into the Classical Era. Strabo briefly mentions how the Turdetani people of southern Iberia have a history and culture that went back 6,000 years. At his time, it had been around 5,600 years since the EEFs had settled Iberia.

While there was widespread destruction, the new order established by the northern invaders quickly surpassed the older in parts of Iberia. Northeastern Spain again shows signs of settlement, and southeastern Spain’s population appears to have increased in the aftermath of the invasion. New methods of ecological exploitation emphasizing use of domesticated animals allowed for sustainable population growth even under the new unideal climate.

EEF rule in Italy was also decisively interrupted in the 23rd century BC. A climate shock disrupted the old ways of life, and weakened the EEF societies of Italy to the point that they were unable to resist invaders. The ancestors of the Iapygians sailed across the Adriatic from the Balkans and established themselves as the new masters of Apulia. The Sicanians (as recorded by Thucydides and confirmed by ancient DNA finds) sailed from eastern Spain and conquered Sicily from their predecessors3, who may have had ties to the peoples of Sardinia. Northern Italy was overrun by the first of many waves of invaders, perhaps speaking Indo-European languages related to poorly attested Ligurian, from what is now Austria and Germany. Large parts of the peninsula were depopulated in the chaos. It would be about five centuries before new invaders - likely the speakers of the Italic languages - would pour into Italy again.

By the turn of the 23rd century BC, Greece had been ruled by the Minoans and their closely related relatives for about a thousand years. They built an agricultural civilization with extensive social stratification and trade. There was extensive contact within the Aegean as well as between Crete and mainland Greece. To their north, Indo-European groups ruled what are now Bulgaria and Albania. While some had roots going back to the Indo-European conquests in the early 3rd millennium, others were more recent arrivals, fleeing a terrible defeat on the Pontic Steppe for the safety of the mountainous Balkans. Those refugees spoke the earliest form of what is now known as Greek.

The Minoans and the other pre-Greek Helladic peoples were populous and sophisticated enough to keep the northern barbarians out of their lands until the Crisis of the 23rd Century. Widespread droughts in the eastern Mediterranean afflicted Greece too, causing famines and social upheaval. Luxury goods disappear from the archaeological record of that time, signs of political complexity vanish, and housing construction changed entirely. Moses Finley described the devastation of the era as:

so massive and abrupt, so widely dispersed, as occurred at this particular time. In Greece, nothing comparable was to happen again until the end of the Bronze Age a thousand years later.

In spite of the widespread destruction, the Greeks were only able to conquer parts of northern Greece in the succeeding four to five centuries. The rest of Greece remained under the rule of their predecessors until the Mycenaean period which began in the 18th century and gradually united Greece into a Greek-speaking alliance network. Thus the genetic impact of the northern invaders was relatively minor by the standards of the time. Only a tenth to a fifth of the ancestry of the later Classical Greeks came from the northern invaders who had originally introduced their language to the region. The remainder came from their predecessors.

Across the Aegean, Anatolia too suffered from the droughts brought in the century of crisis. While both Aegean coast as well as interior Anatolia suffered from the climatic shift, they responded in different ways. Aegean Anatolian sites from the era show severe contraction or outright abandonment in line with signs of general depopulation. By contrast, the political order endured in central Anatolia. While the land was less populous than before, the centers of power grew in size, suggesting political centralization and militarization.

The steppes to the north of the Caucasus Mountains had been inhabited for the previous millennium by the pastoral Catacomb Culture - an Indo-European group native to the steppe which largely lived off of the cattle that it herded. The mountains themselves were inhabited by a variety of peoples. Among those mountain peoples were the shepherding Lola Culture - the descendants of a group which had previously lived some 600 km to the northwest prior to their defeat at the hands of the racially alien ancestors of the Catacomb people around 3000-2900 BC.

The North Caucasus region was afflicted by the climate shift during the 23rd century. Winters became colder and wetter, while summers were drier. That caused issues for the peoples of both the steppe and the mountains. In the mountains, the colder and wetter winters threatened the flocks of sheep. In the steppe, the decrease in the water supply threatened the herds of cattle.

The steppe north of the Caucasus largely depopulated during the crisis. The number of sites found during the succeeding five centuries dramatically lower than the number of sites in the centuries previous. The sites that have been found from the era suggest bitter fighting, with numerous skeletons carrying arrowheads or having broken skulls. The Catacomb people found themselves boxed in between other Indo-European groups advancing from the west (green) while the Lola people (red) marched out of the mountains into the steppe in a desperate effort to save their herds. The Lola people succeeded in conquering the eastern half of the North Caucasian steppe for a time. It would be five centuries before they were destroyed, apparently leaving no descendants.

The South Caucasus fared much better in the crisis than the rest of the world. Its sedentary and semi-nomadic peoples had been devastated three centuries earlier by the invasion of the proto-Armenians from the Pontic Steppe. As a result, the Armenians, their rivals, and their subjects had adopted a more robust way of life based around agropastoralism. Even in the midst of the crisis, the peoples of the South Caucasus continued to construct huge religious monuments and large tombs. Their metallurgical technology continued to advance as well, in conjunction with evidence of political centralization.

The eldest literate civilization, that of the Sumerians, had been conquered by the Semitic Akkadians of Sargon at the beginning of the 23rd century. Sargon’s conquests stretched from the Mediterranean to the Persian Gulf. However, the empire that he forged was brittle and unable to survive the changing climate.

Water levels of the Tigris and Euphrates fell by 150 cm, disrupting the extensive systems of irrigation. In addition, the lack of water made it difficult for farmers to leach the salt from their soils, poisoning their crops. The result was a tremendous fall in crop yields. By 2100 BC farmers in Mesopotamia could grow only a little more than half as much food per acre as their ancestors could three centuries earlier.

Akkad’s rule over Mesopotamia had never been firm. Even under the mighty Sargon the Sumerians had chafed at alien rule and risen in rebellion. A combination of Sumerian rebellion and the invasion of the Gutian barbarians from the Zagros Mountains to the east overthrew the Akkadian Empire. The city of Akkad remains lost to history. The Assyrian and Habur Plains were largely depopulated in the droughts and wars that occurred during the crisis.

The Horn of Africa became drier during the 23rd century and the following centuries. Since the end of the last Ice Age, the Horn has alternated between arid and humid phases. Those phases cause ecological shifts, which in turn drove migrations of peoples. The conservatism of hunter-gatherer societies typically limited their ecological range, resulting in often staggering racial diversity across what are now fairly homogenous areas.

Extant genetic and archaeological evidence suggest that there were three races which lived in East Africa in the distant past. One lived in the Ethiopian Highlands and may have spoken languages distantly related to Chabu. That race still contributes a noticeable amount of ancestry to contemporary Horners - particularly certain tribal groups in the southwest. Another race was distantly related to the speakers of the Tuu languages in Botswana and South Africa. It appears to have practiced fishing and beachcombing. It lived on the coastal fringe of eastern Africa, and may have stretched from coastal Djibouti to coastal eastern South Africa. The third race was in the interior and had distant affinities to contemporary pygmy populations. In the 5th millennium BC it may have reached as far north as Khartoum, but appears to have been pushed far south to the Lake Turkana area by the late 3rd millennium BC.

The Crisis of the 23rd Century brought ruin to some - but not all - of the peoples in the Horn of Africa. The highlands of southwestern Ethiopia were barely touched by outsiders in that period, the tool traditions of the local hunter-gatherers continuing deep into the second millennium of our era. Elsewhere though, history was on the move.

Lake Abbe, on Ethiopia’s northeastern border with Djibouti, was surrounded by forests and woody savannas prior to the crisis. The climate shift transformed the region into an arid steppe. The local fishermen and hunters of local aquatic and terrestrial life were overrun by possibly transhumant pastoralists in the succeeding centuries who sometimes journeyed into Somaliland. They were likely the ancestors of today’s Afar people.

Far to the southwest, water levels in Lake Turkana in Kenya’s Great Rift Valley fell rapidly as the result of the climate shift. Cushitic speaking pastoralists from the Nile River Valley migrated south into the Great Lakes region to take advantage of the drier climates, becoming the ancestors of the Somalis and the Iraqw. Others pressed into southern Somalia - at least Baay province. Their cattle grazed on newly exploitable grasslands abandoned by the hunter-gatherers because of the fall in water supply. They had already mixed with hunter-gatherers in the upper Nile prior to migrating to Lake Turkana and the Great Rift Valley. They didn’t mix with the local hunter-gatherers there for centuries due to their different ecological niches.

The decline in rainfall which resulted in the aridification of the Horn of Africa had effects down the Nile River. Less water flowed into the Nile from its tributaries in Ethiopia’s highlands. Egypt relied heavily on the annual Nile floods to replenish her soils, so the fall of the Nile’s water levels and the diminishment of the annual flooding resulted in great misery. While Old Kingdom Egypt’s extensive water infrastructure and a powerful bureaucratic apparatus had successfully managed to deal with the gradual aridification of north Africa for the previous three centuries, the 23rd century shock proved too much for them. Old Kingdom Egypt managed to endure the initial droughts under Pharaoh Pepi II, but after his long reign the realm disintegrated.

The internal struggle which caused the fall of the Old Kingdom developed at last into a convulsion, in which the destructive forces were for a time completely triumphant. Exactly when and by whom the ruin was wrought is not now determinable, but the magnificent mortuary works of the greatest of the Old Kingdom monarchs fell victims to a carnival of destruction in which many of them were annihilated. The temples were not merely pillaged and violated, but their finest works of art were subjected to systematic and determined vandalism, which shattered the splendid granite and diorite statues of the kings into bits, or hurled them into the well in the monumental gate of the pyramid-causeway. Thus the foes of the old regime wreaked vengeance upon those who had represented and upheld it. The nation was totally disorganized. From the scanty notes of Manetho it would appear that an oligarchy, possibly representing an attempt of the nobles to set up their joint ruled, assumed control for a brief time at Memphis. Manetho calls them the Seventh Dynasty. He follows them with an Eighth Dynasty of Memphite kings, who are but the lingering shadow of ancient Memphite power. Their names as preserved in the Abydos list show that they regarded the Sixth Dynasty as their ancestors; but none of their tombs have ever been found, nor have we been able to date any tombs of the local nobility in this dark age. In the mines and quarries of Sinai and Hammamat, where records of every prosperous line of kings proclaim their power, not a trace of these ephemeral pharaohs can be found.

It was a period of such weakness and disorganization that neither king nor noble was able to erect monumental works which might have survived to tell us something of the time. How long this unhappy condition may have continued it is now quite impossible to determine. In the alabaster quarries at Hatnub quantities of inscriptions nevertheless record work there by the lords of the Harenome, thus indicate that gathering power of the noble houses who disregard the king and date events in years of their own rule. One of these dynasts even records with pride his repulse of the king’s power, saying “I rescued my city in the day of violence from the terrors of the royal house”. A generation after the fall of the Sixth Dynasty a family of Heracelopolitan nomarchs wrested the crown from the weak Memphites of the Eighth Dynasty, who may have lingered on, claiming royal honors for nearly another century.

Some degree of order was finally restored by the triumph of the nomarchs of Heracelopolis. This city, just south of the Fayum, had been the seat of a temple and cult of Horus from the earliest dynastic times, and the princes of the town now succeeded in placing one of their number on the throne. Akhthoes, who according to Manetho, was the founder of the new dynasty, must have taken grim vengeance on his enemies, for all that Manetho knows of him is that he was the most violent of all the kings of the time, and that, having been seized with madness, he was slain by a crocodile.

James Breasted on the First Intermediate Period - the chaotic period of Egyptian history from 2181 to 2055 BC that coincides with the Crisis of the 23rd Century. The First Intermediate Period may have trigged a domino effect of migrations in the lower Nile, with tribes migrating south up the Nile and pushing the ancestors of the Somalis and Iraqw out of Sudan and into the southern part of the Horn.

The Indus Valley Civilization in what is now Pakistan and northwestern India appears to have endured the Crisis of the 23rd Century the best of the contemporary major civilizations. Already used to unpredictable weather from the fickle monsoons, the people of the Indus Valley were able to partly adapt to the drying of rivers and decrease of rainfall by changing the crops that they farmed.

Nonetheless, it is clear that the crisis terribly afflicted them as well. The well developed water infrastructure bought the IVC time, but the centuries long shift in climate nonetheless doomed them. Smaller, less advanced settlements proliferated across the Indus River Valley. The previously unified material culture diverged into a mess of regional material cultures, strongly suggesting political and economic fragmentation. Two centuries after the beginning of the crisis, the cities had declined in population and people began to migrate east. Baluchistan was overrun by invaders from Central Asia who put their new conquests to the torch.

While civilization was diminished but not destroyed in the Indus Valley, the story was different to the south in the Deccan. Archaeological sites in the region show a period of abandonment and widespread burning from 2300-2200 BC, as well as the introduction of cattle from the north. While more research is needed, it appears that northern invaders, perhaps Dravidian-speakers fleeing the decay of the Indus Valley Civilization, swept into the Deccan during the crisis to secure desperately needed food and land.

Central Asia and the Urals experienced the Crisis of the 23rd Century even more bitterly than other regions. Close to the Siberian High, both regions experienced colder winters and heavier snowfall. The Indo-Iranians (linguistic predecessors of the Iranians, Kurds, northern Indians, Pashtuns, Tajiks, etc) of the Sintashta Culture formed in the southern Urals in response, embracing an extremely militaristic way of life that came to emphasize circular fortified settlements along with war chariots. That way of life prepared them for their conquests in the early 2nd millennium BC which included the western half of Mongolia as well as most of Central Asia. To the south in the Marghab River Valley in what is now Afghanistan, farmers migrated from the droughts of the west to Margiana, whose water supply was perhaps enriched by an increase in snowmelt. They formed the Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex. While they would be overthrown by the Indo-Iranians in the coming centuries, they had their two or three centuries of glory amidst a world in flames.

The worsening of Siberian winters drove migrations within that beautiful but dangerous land. Stone age tribes, never more than a week away from starvation, were forced to fight or die for the huge expanses of land which could barely sustain them. The most successful were the Ymyyakhtakh, a polyethnic group of tribes perhaps centered around a Yukaghir-speaking core originating in the upper Lena River Basin in southern Yakutia.

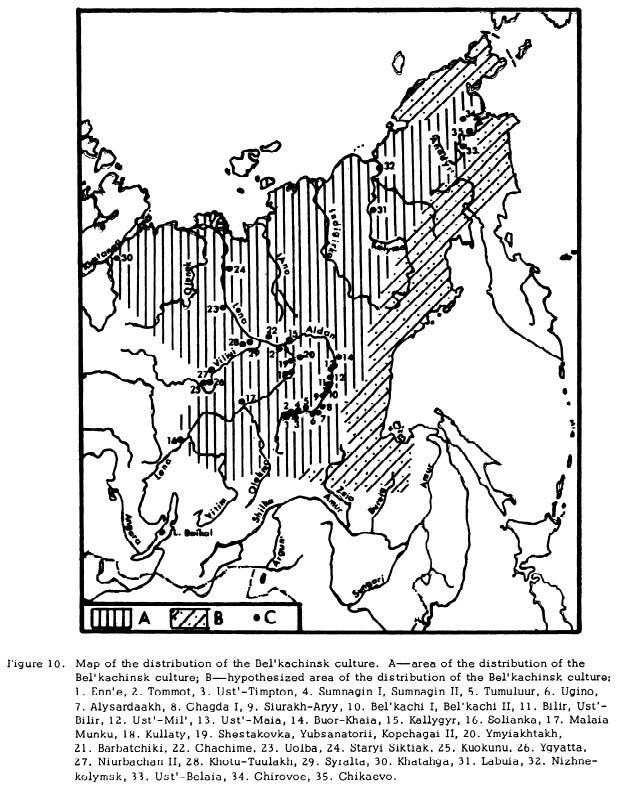

Prior the Crisis of the 23rd Century, a great arc of land stretching from the Altai Mountains north into central Siberia into Yakutia and Chukotka (but excluding Buryatia) was inhabited by races with affinities to Amerindians. One of those peoples, bearing the Bel’kachi culture, had been successful in spreading across much of northeastern Eurasia in the previous fifteen hundred years. The Bel’kachi people presumably mostly spoke Dene-Yeniseian languages - a language family whose last remnants are now spoken in the American Arctic, the American Southwest, and central Siberia along the Yenisei River. Some of their relatives had crossed the Bering Strait about eight centuries prior to the crisis, introducing the Dene-Yeniseian languages to the Americas. However, some Bel’kachi people appear to have spoken Uralic languages.

Whether the Bel’kachi were weakened by the colder climate to the point that the Ymyyakhtakh were able to overrun them, or the Ymyyakhtakh were simply militarily superior to the Bel’kachi, the effect was the same. In the centuries following the crisis the Ymyyakhtakh mostly overran the Bel’kachi/Dene-Yeniseians. In Yakutia this involved the replacement of about half of the population by the southern invaders. To the west, the ancestors of the Yeniseians such as the Kets fell into the Indo-Iranian sphere of influence and avoided conquest by the Ymyyakhtakh by hiding in mosquito-infested areas. The Samoyedic peoples in central Siberia experienced the Ymyyakhtakh invasions from the east differently. The ancestors of the Selkup, many of them Yeniseians, also survived under the Indo-Iranian aegis. The find of kra001 on the banks of the Kan River in Siberia suggests that the ancestors of the Yeniseians endured to the north of the river, further down the Yenisei, but south of the ancestors of the Nganasans. The ancestors of the Nganasans were mostly Ymyyakhtakhs. To the east, the Dene-Yeniseians appear to have had holdouts in Chukotka4 that may have lasted into the Common Era prior to their final defeat, near-extermination, and absorption at the hands of Chukotko-Kamchatkans. The Ymyyakhtakh Expansion in the centuries following the Crisis of the 23rd Century split the old Dene-Yeniseian continuum that had stretched from the Yenisei River deep into Alaska in two - the Yeniseians in central Siberia, the Na Dene in Alaska.

The Ymyyakhtakh invaders of Chukotka, following the migratory paths of walruses to Wrangel Island, found the last woolly mammoths in the aftermath of the crisis. They hunted them into extinction before abandoning the island.

The ancestors of the Saami east of the Urals were influenced by the expanding Ymyyakhtakh and pushed west over the mountains. They journeyed west past the Pechora and Mezen Rivers until they found safety in northern Scandinavia. They appear to have been ill-fed and lived miserable lives in the harsh lands of the far north. Nonetheless, they survived and their descendants reign in the far north of Scandinavia to the present.

The last remnants of the Eastern Hunter-Gatherer race had fled to the far north of what is now European Russia following the Indo-European conquests early in the 3rd millennium. The colder winters and heavier snowfalls that afflicted the peoples of Central Asia, the Urals, and Siberia afflicted them too. The invading Saami absorbed them in northern Scandinavia and the Mezen River Basin, although they appear to have survived in the Pechora River Basin prior to the invasion of the Permics (ancestors of the Udmurts and Komi) during the Bronze Age Collapse a thousand years later.

Much as elsewhere, there were winners in East Asia as well as losers. The farmers from the Yellow River Valley who had introduced millet and the Tibetan languages to the Tibetan foothills were overrun by the neighboring hunter-gatherers in the centuries following the crisis. The resulting mix of the conquering hunter-gatherers and their ex-farmer subjects formed what we know today as the Tibetans. The farming lifestyle had proved ill-adapted and the hunter-gather lifestyle more robust for the cooler climate.

The Yellow and Yangtze River Valleys had grown tremendously in population and complexity over the course of the 3rd millennium BC. Cities, fortresses, and towns dotted the river valleys. The Crisis of the 23rd Century ended many of them. The monsoons weakened and moved south, resulting in droughts in western China. The droughts led to the increased concentration of silt in the Yellow and Yangtze Rivers, resulting in devastating floods.

The floods were accompanied by widespread warfare. In the Yellow River Basin, the Taosi archaeological site in Shanxi suffered both floods and a city sack. It appears to have been the capital of a kingdom, and possessed an observatory. In the eastern and lower Yangtze River Basin, the Liangzhu civilization (possibly related to the ancestors of Hmong) collapsed from flooding and was overrun by northern invaders. Some remnants of the Liangzhu however do appear to have endured for a few centuries, diminished in both population and sophistication. The Shijiahe civilization in the middle Yangtze also collapsed in the aftermath of the Crisis of the 23rd Century. All of its large earth enclosures were abandoned, its settlements shrank in size, and archaeological evidence points to an invasion of northerners from the Yellow River Valley.

In spite of the terrible misery and widespread destruction, a new order emerged from the chaos in China. Influenced (but not descended from, contra Beckwith) by the peoples of the Eurasian Steppe and Siberia, it combined the elements of agricultural civilization with pastoralism and bronzeworking into a new cultural synthesis. The new agropastoral societies of northern China - whether in the Liao River Basin like the Lower Xiajiadian tribes, the Ordos Loop like the Zhukaigou shepherds, or in the upper Yellow River like the Qijia horsemen - were able to thrive and progress in the drier climactic conditions.

The Crisis of the 23rd Century showed the fragility of the civilizations of the Bronze Age. Large and politically sophisticated populations reliant on reliable flows of water and fertile soil were deeply vulnerable to changing conditions. It was instead those societies which exploited a wide range of ecologies through hunting, pastoralism, and farming which endured the best. They could not mobilize the resources of the agricultural societies in the best of times, but they were able to avoid the worst times. That pattern would be seen again during the Bronze Age Collapse, the Fall of Rome, and in areas which saw the disintegration of state authority in the early modern period.

contemporary racial labels are not really appropriate for populations of the 3rd millennium. “White” for instance a poor physical description of central Europeans at the time. Their skin color was generally swarthy rather than fair because genetic selection for fair features appear to have been largely centuries in the future.

Thucydides was aware of this invasion, likely from the Elymian embassy that visited Athens

the Dene-Yeniseians in Chukotka may have been wiped out entirely, only for their partly-Amerindian cousins in Alaska to resettle parts of Chukotka later on before being wiped out by the Chukotko-Kamchatkans again

Thanks for this whopper of a post, I genuinely wasn't sure you'd manage to sweep over the entire planet for this time period, but you managed it very well, just as advertised. Both wide in scope as well as synthetic.

Heroic effort. Thank you!