It was 9:00 am in the city of Slavyansk in eastern Ukraine, on 12 April 2014. A group of 52 armed men, about 80% of them Ukrainian citizens, stormed the city’s Interior Ministry building. The government policemen in the building opened fire on the armed men, but quickly surrendered to the larger force after they fired automatic weapons into the building. The armed men, led by the shadowy Russian Colonel Igor Strelkov, tore down the building’s Ukrainian blue and yellow flag. They raised the Russian white, blue, and red tricolor.

Strelkov and his men formed the nucleus of a rebellion in Ukraine’s east. Bolstered by locals unhappy with the overthrow the Ukrainian government in February 2014 as well as by foreign volunteers, they fought a series of battles in the predominately Russian-speaking Donbass region that lasted into August before a Russian intervention saved the rebellion.

History is a complex tapestry with many threads, and is constantly rewoven. Sometimes threads decay and disappear. Other times old threads are strengthened. Some threads are ripped out, and replaced with new threads. The shapes made on the tapestry are usually agreed upon, but the story they tell is usually disputed.

To understand the roots of the Donbass Wars and the Russian-Ukrainian conflict, one must first identify the important historical threads. Some such as the recent growth of Protestantism in Ukraine are quite new. Others are very old, and to understand them one must go back deep in the past.

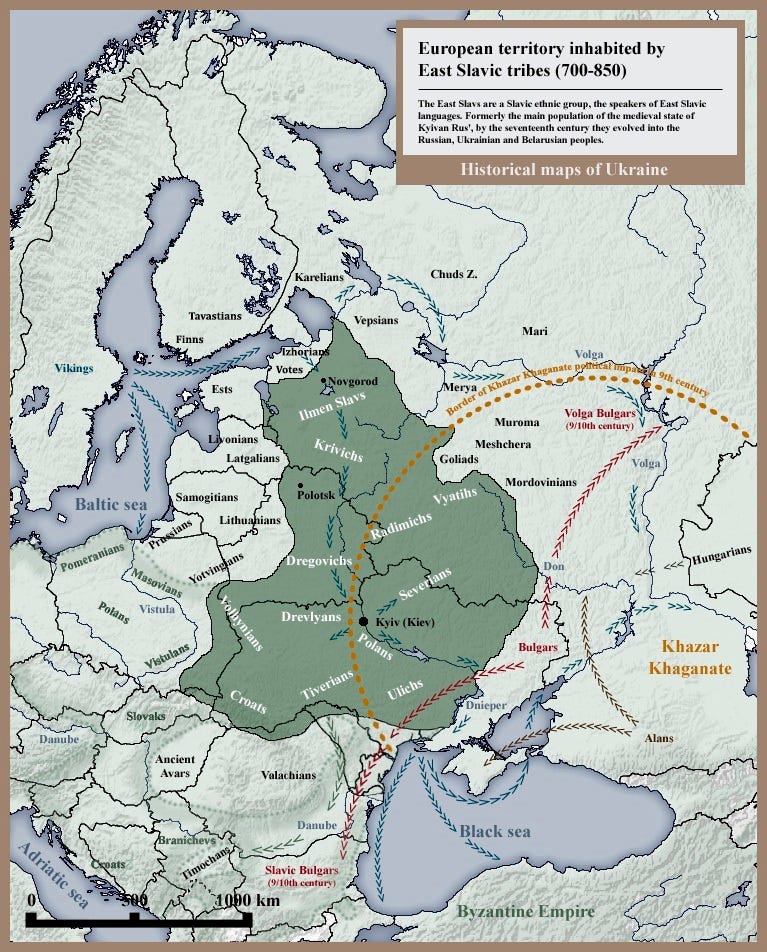

The Russians and Ukrainians are both East Slavic peoples, the largest branch of the Slavs. Kin to Bulgarians, Poles, Czechs, Serbs, Croats, Slovaks, and others - they descend from a small group that lived in Belarus and north-central Ukraine 1500 years ago. The original Slavs were a primitive people, and hid in the forests and swamps from a long succession of Iranian and Germanic nations that ruled the steppe to their south.

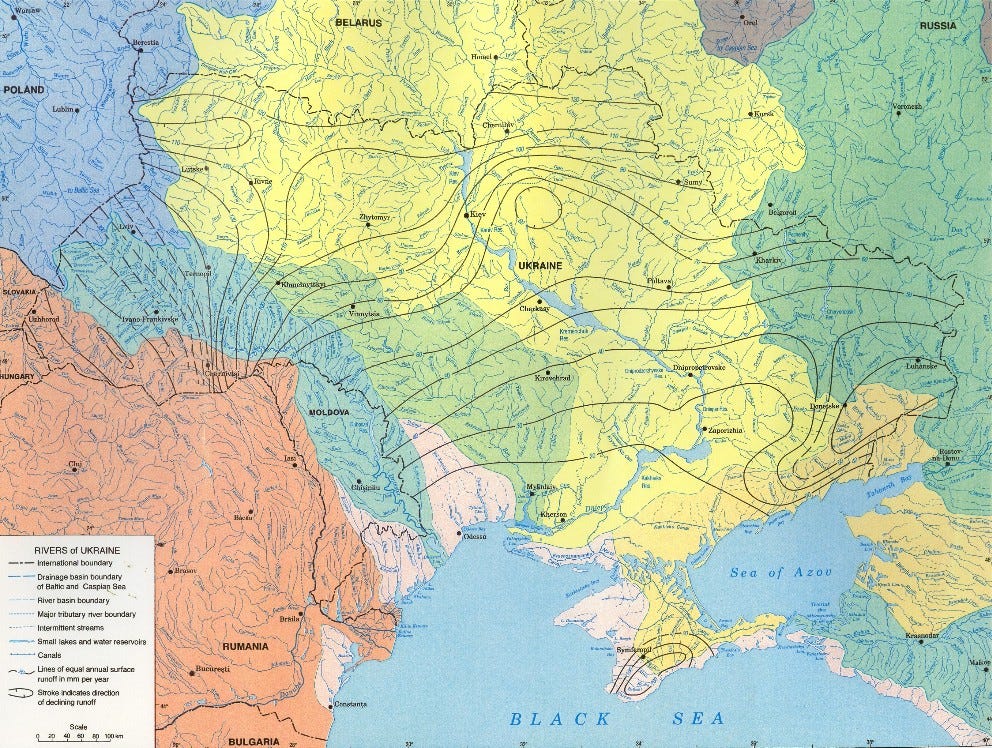

The steppe is a relatively flat and grassy ecoregion that stretches from Hungary in the west to Manchuria in the east with only a handful of barriers. Most of Ukraine is part of the Pontic Steppe, which stretches from the Carpathian Mountains in the west of Ukraine (pictured in the map below) to Kazakhstan. Part of the Pontic Steppe in Ukraine is more properly called a forest-steppe as it is a transition region from the steppe proper to the forests of the north. While also fairly flat, the forest-steppe has patches of trees and a more varied ecology.

The steppe offered no protection for any nation, and the lack of natural defenses made it a risky place for people to develop. Raiding was easy and defense was difficult. So for thousands of years, nomadic horsemen ruled the region. They grew some crops, but focused on herding their cattle, sheep, goats, and horses. Faced with threats, they could run away and live with much of their wealth in animals. By contrast, sedentary farmers who fled their fields would become impoverished and starve. The farmers could not bring much of their wealth with them.

The Slavs, as farmers, were thus restricted to living in the lands north of the steppe in what is now Belarus and northern Ukraine. There, the steppe nomads found it difficult to guide their animals through forest paths, or to defeat Slav warriors in battle.

In the 4th and 5th centuries AD, Europe was convulsed by the arrival of a new nation of steppe nomads: the Huns. Driving the Goths (known to archaeologists as the Chernyahov Culture) out of Ukraine and into the Roman Empire, they left a vacuum in the Pontic Steppe that was quickly exploited by the Slavs. No longer restricted to their miserable forested and swampy home, the Slavs colonized much of the steppe along the Dnieper and Dniester Rivers by the 6th century. Others spread west into Poland and eastern Germany. The Slavs grew rapidly in population during this period, but it was not to last.

The first group of Mongols to invade Europe, the Avars, arrived in the mid-6th century. The Slavs their first victims. While the Slavic state or states were destroyed, the Slavs themselves were not. Many joined the Avars as they rode west, and settled in the depopulated lands of the Balkans. It is at this time, around 600 AD, that the Slavs began to fragment. Separated by distance and no longer united politically, dialectical differences began to emerge. Those would eventually evolve into new languages.

The Slavs of eastern Germany, Poland, Czechia, and Slovakia developed the West Slavic languages. The Slavs of the Balkans - Croats, Serbs, Bulgarians, and Slovenes- developed the South Slavic languages. The Slavs who stayed in the east - the ancestors of the Russians, Ukrainians, and Belarusians - still spoke a common East Slavic language.

The Avars were succeeded on the Pontic Steppe by several more Turkic nations, among them the Bulgars. The Bulgars migrated to the Balkans and the middle Volga in the mid-7th century under the pressure of the Khazars, becoming the Bulgarians and the Volga Bulgars respectively.

The Khazar dominance of the Pontic Steppe shielded the Slavs from the worst of the steppe nomads. A single hegemon may be oppressive, but for Slav farmers it was more predictable than multiple feuding powers. The East Slavs again grew in population under countless forgotten chiefs and petty kings who reigned in the shadow of the Khazars. As they grew in numbers, the Khazars were increasingly unable to control the Slavs, and Slavic wealth attracted foreign merchants.

In the 8th century AD Scandinavian seafarers reopened an old trade route from the Baltic Sea down the Volga River, connecting northeastern Europe with the Caucasus and Iran. This trade route mostly bypassed the East Slavic tribes and passed through the Khazar realm. In the early 9th century, this changed. With a series of migrations causing chaos on the Volga, the Scandinavian seamen shifted their trade route from the Volga River to the Dnieper River, sailing to the Black Sea and Byzantium rather than the Caspian and Iran.

The river trade routes could bring the Scandinavians great wealth, but were also treacherous. Sailing across the Baltic, they entered the Gulf of Finland, then entered the Neva River at its mouth in what is now Saint Petersburg. Sailing up the Neva, they entered Lake Ladoga, then took the Volhov River to Lake Ilmen. At Lake Ilmen, they sailed up the Lovat River, then its tributary the Kunya River. There, they would disembark and carry their boats to the nearby Toropa River. Sailing down the Toropa, they would enter the Western Dvina, and sail upriver to the Kasplya River. After sailing upriver again for a time, they would disembark and carry their boats to the Katynka River. There they would sail the length of the Katynka to the Dnieper until they reached the Dnieper Rapids. The Dnieper Rapids included nine major and up to forty minor rapids, and stretched for 65 kilometers - all of it along the steppe. The seamen would have to carry their boats overland for that part of the journey, and were horribly exposed to attack from the horseriding steppe nomads. If they survived to pass the Dnieper Rapids, the seamen would sail the remaining part of the Dnieper River to the Black Sea, and from there to the Byzantine Empire and the Mediterranean.

The journey was dangerous but rich enough that those Scandinavians, called the Varangians, built forts at strategic locations along the trade route. Many of the locations were picked because they were at portages. A portage is a location where two river systems are close by, and where seamen would traditionally disembark from one river and move their boat by land to another river. Other forts were built at the mouths of rivers, or at river confluences. From there, a chief, pirate, lord, or other military man could capture trade ships or force them to pay a toll. Thus political authority grew out of trade.

In the mid-9th century, a Varangian group called the Rus’ was invited by a collection of East Slavic tribes to rule over them. The Rus’ leader, Ryurik, agreed. Of Finnic paternal ancestry, Ryurik was culturally a Varangian. He, his descendants, and their Varangian retainers would unify most of the East Slavs into a new realm. While the East Slavs kept their tribal names for a time, the Dregovichi, Krivichi, Vyatichi, Drevlyane, and Ilmen Slovenes all came to see themselves as Rus’ in fits and bursts.

Leveraging their wealth and control of trade, the Rus’ warred with the Khazars, the Volga Bulgars, and the Byzantines in the 9th and 10th centuries. Under the reign of Svyatoslav in the mid-10th century, the power of the Khazars and the Balkan Bulgarians was broken, and the Rus’ emerged as the dominant power of eastern Europe. Dying young, Svyatoslav left his realm divided between his sons.

Then rose Vladimir the Great. Claiming to be the bastard son of Svyatoslav and his housekeeper, Vladimir raised a Viking army in Scandinavia and invaded the Rus’ realm. Slaying Svyatoslav’s other sons, he established himself as the ruler of the Rus’ by 980 AD. Likely desiring access to the riches of Byzantium, he agreed to convert his people to Christianity in return for a Byzantine princess as a bride. The Byzantine Emperor, needing allies against rebels, agreed to marry his sister to Vladimir in return for soldiers. The Rus’ were then converted to Christianity in 988, and a Christian Metropolitan was installed in Kiev. The East Slavs thus were united under one state, with one ruler, and one god.

Warring against his neighbors, Vladimir left his many sons to govern the Rus’ realm. They recruited their own retainers and raised soldiers for their father, going on campaigns with him, or garrisoning forts. This, as well as the growing Christian Church, served to integrate the Rus’ realm.

The steppe remained a perpetual thorn in the side of Vladimir. With the Khazars destroyed by his claimed father Svyatoslav, a new nomadic nation, the Pechenegs, migrated to the Pontic Steppe. It would be Vladimir’s son, Yaroslav, who would have to defeat them.

After Vladimir the Great’s death in 1015, the Rus’ realm fragmented. Like many medieval realms, the Rus’ lacked institutions capable of ensuring orderly successions. Vladimir’s many sons warred with each other over who would be his successor, and who would rule the Rus’ capital of Kiev. In the end, Yaroslav the Wise emerged triumphant, and ruled all of the Rus’. In an effort to prevent future intra-dynastic warfare, Yaroslav left a testament to his sons. In the testament, each of his sons was to be given their own part of the Rus’ realm to govern, but his eldest son was to be given Kiev and understood as the leader of the others. Kiev’s control of a narrow point of the Dnieper River as well as its hosting of a Christian Metropolitanate made its importance even greater than political significance.

Yaroslav’s testament failed, and despite periodic attempts at the reunification of the Rus’ the realm remained fragmented. The descendants of Ryurik, the Ryurikovichi, continued to rule their increasingly small principalities, each divided into even smaller principalities upon succession by a ruler’s sons. Councils were held irregularly between the princes to organize a front against foreign threats, most commonly the steppe nomads. Some of the Rus’ principalities built long wood and earth walls on the steppe that stretched for hundreds of kilometers to protect themselves from nomadic raids.

Even as the realm fragmented in the period between the death of Yaroslav and the arrival of the Mongols, it grew wealthier and more advanced. A new strain of rye spread across Eastern Europe, allowing farmers to sow a winter crop that they could harvest in spring in addition to the traditional summer crop that they harvested in the fall. The Rus’ population boomed as a result. In the 11th century there were 89 towns in the realm, in the 12th century there were 223, and in the early 13th century there were about 300. The total population was between 7 and 8 million - vastly larger than the Finno-Ugric peoples to the north and the Turkic steppe nomads to the east. The population boom allowed the Rus’ to demographically drown the Finno-Ugrians of what is now Moscow and the surrounding regions. While the Rus’ in the north mixed more with the Finno-Ugrians than their southern cousins, they remained racially quite similar.

Trade and labor specialization naturally increased with larger populations and the development of towns. Trade was conducted along three main routes. The first two were the old Varangian routes down the Volga and the Dnieper. But the third - at the southwestern corner of the Rus’ realm - was new. The regions of Galicia and Volynia in modern day western Ukraine had access to several rivers. They could sail west on their rivers to the Dnieper and the Black Sea, go south to the Danube and into Central Europe, north to the Vistula River and the Baltic Sea, or southeast to the Dniester and the Black Sea by a route that didn’t pass by potential enemies on the Dnieper.

Transportation by sea even in the present is cheaper than transportation by land. In the past, it was even more economically competitive, and unlike land transportation, required little capital investment. Thus trade and military power grew out of rivers. Religion, language, and much else spread by them too.

Hydrology shaped the history of the East Slavs greatly after the fragmentation of the Rus'. The Rus’ of the north - in Novgorod and Pskov - developed their own dialect as the Middle Ages proceeded, their lives being entwined with the Neva and the Baltic rather than the Dnieper. Similar processes drove the development of dialects in other parts of the Rus’ realm. In the swamps of modern Belarus, the isolated populations slowly developed what would become modern Belarusian. Similarly, in Galicia, the people who traded with the Poles and the Hungarians developed the earliest version of what would become Ukrainian.

These dialects were not the only dialects that were forming at the time. Political fragmentation and poor communications meant that there were undoubtedly many other dialects in use - some as widespread as entire principalities, others only spoken in isolated villages. Belarusian, Ukrainian, Russian, and their internal dialects are the only ones that have survived.

Similar linguistic processes occurred in Germany, where Dutch and Flemish evolved to become separate languages from standard German due to political fragmentation and geographic isolation. In France, other dialects were completely stamped out by centralization measures in the last few centuries. Spain by contrast still deals with separatists speaking a different Romance language whose history was shaped by their engagement with people in the Mediterranean basin rather than the Atlantic basin. Dialectical leveling or differentiation was partly political, but also partly hydrological.

The fragmentation of the Rus’ realm from the 11th to early 13th centuries created two states in what is now western Ukraine: Galicia and Volhynia. Bitterly divided in the 12th century, they were united under the personal rule of Roman the Great in 1199. In his brief reign, Roman curbed the power of the nobility, made an alliance with Poland against the encroaching Hungarians, and conquered Kiev.

Dying early, Roman left Galicia and Volhynia in a state of chaos. Hungarians, Poles, Rus’ from Novgorod, and Lithuanians invaded - all staking their claim for the wealthy region. Briefly, a local noble - the only ruler in Kievan Rus’ not claiming descent from Ryurik - ruled the region. Ultimately, Roman’s son Daniel took the throne and reunified Galicia and Volhynia.

Daniel’s reunification of Galicia and Volhynia was complicated by a new threat: the Mongols. The most dangerous steppe empire in millennia, the Mongols had overrun China, Central Asia, Iran, and the Pontic Steppe. Devastation followed in their path. The Rus’ too, were their victims.

Kolomna, Rostov, Uglich, Moscow, Yaroslavl, Kostroma, Kashin, Ksnyatin, Gorodets, Galich, Ryazan, Pereslavl, Yuriev-Polsky, Dmitrov, Volokolamsk, Kozelsk, Tver, Torzhok, Vladimir, Kiev, and other cities were all destroyed by the Mongols from 1237-1240. At a minimum, hundreds of thousands died. The fragmented statelets of Rus’ were devastated. Galicia-Volhynia was no exception, but still fared better than others.

The Metropolitan of Kiev disappeared in the chaos of the Mongol invasion, likely slain with most of the city population during the Sack of Kiev in 1240. The Mongol invasions thus disrupted the religious as well as political and economic institutions of the Rus’.

Medieval rulers understood the importance of religious institutions. The Orthodox and Catholic churches were not purely religious institutions, but wielded great economic influence due to their extensive landholdings. They dominated education and learning, and could provide a class of administrators for the state. Perhaps even more importantly, they were a parallel power structure, providing an alternative basis of legitimacy compared to purely secular authorities.

Thus for reasons beyond mere prestige Daniel sought to have his candidate chosen as the new Metropolitan of Kiev. While the Orthodox Christian Patriarch in Constantinople agreed to make his candidate the Metropolitan, he demanded that he not reside in Galicia due to Daniel’s dealings with the hated Catholics. Thus Metropolitan Kirill was appointed to the devastated city of Kiev. To Daniel’s dismay, he moved away from the devastated capital of the Rus’ and to faraway Vladimir - 200 kilometers away from Moscow. Bereft of a nearby Metropolitan, Galicia was eventually granted its own Metropolitan in 1303 in its capital city of Halych. While Poland later dissolved the Halych Metropolitanate, it was resurrected in the 1530s.

Religious structures in the Rus’ world became fragmented much as the political structures had, with long lasting consequences. With poor communications, widespread illiteracy and religious syncretism, the practices of Orthodox Christians in different religious hierarchies diverged. Religious identity in the pre-modern period was concerned less with actual beliefs and more with proper execution of religious rituals, so differences in rituals added to the growing distinctiveness of Rus’ people in what would become the western Ukraine and the Golden Ring around Moscow in Russia.

In the mid-14th century there were two metropolitans in Rus’. The first, the Metropolitan of All Rus’, was in the city of Vladimir but moved to Moscow in 1325. The second, the Metropolitan of Little Rus’, was in Halych. The Metropolitanate of Little Rus’ administered six of the fifteen old eparchies (a province in the Orthodox Church, comparable to a Roman Catholic diocese and ruled by a bishop) that had been under the jurisdiction of Kiev - including much of what is now Belarus in addition to Ukraine.

Untrusting of the volatile Rus’ princes, the Mongols developed a working relationship with the Orthodox Church. Church lands and priests were exempted from taxes, and their civil and criminal authority was extended. Remote areas once beyond the reach of Orthodoxy were brought into the Church’s embrace. The status of Orthodoxy rose under the Mongol Yoke, and the Christianization of the East Slavs was completed under it. The political stability that the Mongols created in the 13th and 14th centuries were a welcome respite from the decades of princely struggles for many of the East Slavs. Whereas early medieval divides between the Rus’ had been merely political, the Mongol invasions had begun a divide of religious institutions.

Invasions from the north and west would add to the growing distinctiveness of the East Slavs of Belarus and Ukraine. Following the extinction of the princely house of Galicia-Volhynia in 1323, a Mazovian (sub-ethnicity of Poles, a West Slavic nation) prince took the throne. He was loathed by the local nobility in spite of his conversion to Orthodoxy, and poisoned in 1340. The realm fell into anarchy for the rest of the decade, with Poles, Lithuanians, and Mongols fighting for the control. In the end, the Poles secured Galicia, the Lithuanians Volhynia. Many Poles settled in Galicia, beginning a long presence that would only end in the Second World War.

The Lithuanians are a Baltic, rather than Slavic people. Comprised of feuding pagan tribes at the dawn of the second millennium, they gradually unified in the face of the advancing Germans of the Teutonic Order. Over the course of the 13th and 14th centuries, the Lithuanians took advantage of the power vacuum in the western Rus’ lands. Even as they lost ground to the relentless Teutonic Order in their homeland, they were successful against both the Mongols and the Rus’. Belarus, most of Ukraine, and parts of modern Russia were under Lithuanian rule by the end of the 14th century.

The Lithuanians were a primitive people compared to the Catholic Poles to the west and the Orthodox Rus’ to the east. Their conquest of many Rus’ lands thus drove not a Lithuanization of the East Slavs, but a Slavicization of the Lithuanians. The Lithuanians adopted the written Rus’ language as they lacked their own system of writing. Lithuanians princes married Rus’ noblewomen and gave their children Slavic names. Some accepted Orthodox baptism. The Lithuanian Grand Duke Jogaila, later King of Poland from 1386-1434 had a Rus’ princess for a mother and spoke the Rus’ language even though he identified as a Lithuanian. Other Lithuanian Grand Dukes also spoke the Rus’ language natively into the 15th century.

Had Lithuania remained an independent state, it would have eventually become Orthodox and East Slavic speaking. Lithuanian polytheism was ill-adapted for the increasing sophistication of the late medieval world, and made Lithuania a target for Catholic crusaders. In addition, Lithuanians were a mere 20% of the populations and only half of the nobility. In time they would have been absorbed by their East Slavic subjects, and indeed were being absorbed in the course of a few decades of rule over parts of the Rus’ lands. Lithuania even made an effort in the 1360s to restore the Orthodox Metropolitan to Kiev so as to bring the Orthodox Church in their lands under their control. However, fate would drive the Lithuanians and the Rus’ apart.

In spite of the consolidation of the Lithuanian state into first a kingdom, then a Grand Duchy, its geopolitical position remained unenviable. The fanatical Teutonic Order, reigning out of what is now Kaliningrad, regularly sailed down Lithuania’s rivers from the Baltic to raid its heartland. The Order’s knights, living for nothing but prayer and war, were more than a match for Lithuanian tribesmen. The Order also skillfully used Lithuania’s internal dynastic disputes to improve its position. The Order’s objective was to sever the pagan core of Lithuania away from the Orthodox Rus’ lands - a task made easier by the growing power of Moscow. Moscow’s defeat at the hands of the Mongols in 1382 bought the Lithuanians time, but they understood they needed to rethink their position. The Order was not going to stop attacking Lithuania.

Poland in 1385 had a mere girl, Jadwiga, as its ruler. The Polish nobility, having lost their links to Hungary, were worried about the Luxembourg family’s control of Brandenburg, Hungary, Bohemia, and the Holy Roman Empire. They wanted Jadwiga to marry a powerful ruler to balance out the Luxembourgs. The obvious candidate was Jogaila, the Grand Duke of Lithuania.

The Lithuanians saw that they could benefit from a dynastic union with Poland. The Poles could aid them in converting to Catholicism. Conversion to Catholicism would reduce the military threat of the Teutonic Order by removing the justification for its crusades, balance out the growing strength of Moscow, and would provide Lithuanians a religious distinctiveness that would prevent the masses of their Orthodox Rus’ subjects from assimilating them. Thus Jogaila agreed to the Union of Krewo and to marry Jadwiga. Poland and Lithuania were thus united, though weakly.

Lithuania’s conversion to Catholicism and the union with Poland alienated many of Lithuania’s Orthodox Rus’ subjects. Rus’ political structures such as the Principality of Kiev were abolished, their hereditary nobles replaced by appointed officials. Certain failed dynastic maneuvers in Lithuania were backed by Orthodox nobles, and their failure served to discredit their cause and advance that of the Catholics.

Nonetheless, Poland-Lithuania’s tolerance of Orthodox nobles and institutions was to fluctuate in time and space over the next three centuries. In general Lithuania was more tolerant of Orthodoxy than Poland, its pagan heritage lending it a sympathy to other creeds. Orthodox Rus’ nobles were given full political rights in Lithuania in 1434, while in Polish controlled Galicia many were forced into exile. Some Orthodox Rus’ would emigrate to the lands of Moscow.

Moscow, merely a small town at the beginning of the 14th century, was an unlikely place to evolve into a great power. Nearby Vladimir and Tver were the obvious candidates to rise to preeminence among the northeastern Rus’ states. It was precisely because Moscow was so small and unimportant that it rose to power. Loyally serving the Mongols of the Golden Horde in the 14th century, Moscow was rewarded with wealth and power.

Moscow’s growing strength was aided by internal bloodletting. Republican forms of government were unable to scale much beyond the level of city-states in the Middle Ages, so large states were invariably bound together by complex networks of marriage alliances and feudal contracts. Heterogeneity and particularity rather than homogeneity and universality were the norms in medieval politics, with religious leaders (as well as the Mongols) among the few maintaining universal pretensions. Thus the leading causes of serious dissention and civil strife were dynastic disputes. A ruler would have multiple sons, who upon the death of their father would either divide their state into smaller and weaker pieces, or would fight each other and bleed the realm.

Moscow was blessed by two major dynastic die offs. The first was the Black Plague, which killed most of the nobility and the ruling family. As a result of the Plague, the survivors were bound closer together. Servitors could rise to become powerful noblemen, thus offering opportunities for advancement and banishing the terrible jealousies that poisoned the climates of more exclusive courts. The second die off occurred in the wars for succession in Moscow from 1434 to 1453. Vasily the Blind emerged as the victor. Many of his relatives who could have claimed the throne perished in the fighting or fled abroad, and most lands previously held as appanages fell under the direct control of the Grand Duke. In addition, the principle of primogeniture was upheld, with the eldest son of the ruler guaranteed to be the sole inheritor of the state apparatus. Centralization would remain the dominant political tendency within Russia over the course of the next half-millennium.

By contrast, the union of Poland and Lithuania had far more centrifugal tendencies- tendencies that would eventually lead to the downfall of their nations. The nature of their union meant that the nobility remained powerful, particularly in Lithuania. The Lithuanian nobility remained untrusting of the intentions of both the Polish nobility and monarchy into the 1460s, rightfully fearing that the Polish king intended to strengthen his domestic position with the annexation of part of the Teutonic Order’s lands and that the Polish nobility wanted the Rus’ lands held by Lithuania.

Such fears and lack of trust were only partly obviated during the Russian invasions of Lithuania in the late 15th and early 16th centuries. Ivan III declared to Lithuania in 1493 that he, not the Catholic dynasty of Poland-Lithuania, was the true ruler of all Rus’. The privileges and rights granted to the Orthodox Rus’ nobility under the Lithuanians kept most of them loyal during the ensuing struggles - in particular Grand Duke Alexander of Lithuania’s 1494 edict confirming the privileges of the Orthodox Church granted by Yaroslav the Wise in the 11th century. The Lithuanian nobility’s class interests were in liberty for themselves and oppression for their serfs - not for a unified Russian state with an all-powerful ruler.

The liberty for nobles in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania that kept them true wasn’t the result of the strength of the government, but rather its weakness. After the death of Casimir IV in 1492, the Lithuanian nobility forced Casimir’s successor, Alexander, to agree to a set of privileges in return for their votes in his ducal election. While the agreed privileges included protection against imprisonment without criminal conviction that benefitted all noblemen, the privileges mostly benefitted the great landholders. The Grand Duke of Lithuania (sometimes the same as the King of Poland, but at that time a separate, subordinate ruler in a dynastic union) had to seek the ducal council’s advice and receive approval from the council in order to perform a number of actions. Those actions included the dispatch of ambassadors, appointments and dismissals to and from offices, lease cancellations, and most importantly government expenditures. The Grand Duchy of Lithuania had thus formally evolved into an aristocratic oligarchy. The Grand Duke would retain his ducal lands, but the great landholders would be the dominant force to the end.

The Orthodox Rus’ nobility of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania grew in strength and influence in the 15th century. A mere 3.4% of leading families in Lithuania between 1387 and 1413, they became 19.6% between 1413 and 1447 and 37% by 1492. One notable Orthodox Rus’ nobleman who served Lithuania was Konstantin Ostrozhsky. Ostrozhsky was so trusted that he was appointed as the castellan of Vilnius in 1511 - the capital of Lithuania and deep in its heart. It is because of the extensive Rus’ involvement in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania that some Belarusian nationalists (zmagars) identify it as the predecessor to the modern Belarusian state.

Lithuanian fears about Polish aggrandizement at its expense were well founded. During the second phase of the Livonian War 1547-1583 in the 1560s, Poland used its financial and military contributions to the conflict (existential for Lithuania, whose northern and eastern frontiers were under Russian invasion) as successful leverage for closer integration. The Union of Lublin in 1569 replaced the merely dynastic union (the ruler reigning simultaneously in two separate countries with their own laws and institutions) with a real union (where the ruler reigned in one united realm). While the Orthodox Rus’ of Galicia had long been under Polish ruler, the Union of Lublin transferred the predominantly Orthodox Rus’ lands of Volhynia, Podolia, and Kiev from Lithuania to Poland as well. The branch off of the medieval Rus’ that modern Ukrainians and Belarusians both claim thus split. The ancestors of the Ukrainians were to be under Poland, the ancestors of the Belarusians under a truncated Lithuania.

Conditions for ordinary people worsened over the course of the 15th and 16th centuries in Ukraine. The Polish government, dominated by the nobility, gradually restricted the ability of peasants to leave the lands that they worked. In 1518, the Polish government decided to reject any complaints made by subjects not owned by the crown, opening peasants up for even worse abuse. In 1557, peasants lost any rights they had to land. In 1573, peasants were forbidden from leaving the lands that they worked altogether. Freeholders were rare in 16th century Poland, as were crown or church serfs. The vast majority of the population lived and worked on estates owned by nobles. Thirteen families controlled 57% of all of the land in Volhynia, and one family ruled almost the entire left bank of Kiev. Whereas in Russia the state grew stronger with each territorial acquisition as it could distribute more land to its servicemen and tax it to pay its bureaucrats, in Poland-Lithuania it was the nobility who grew stronger. By 1640, a tenth of landholders in Ukraine ruled over two-thirds of the population.

Poland had always been less tolerant of Orthodoxy than Lithuania, and sought to bring the Orthodox hierarchy under its sway. A nobleman of Rus’ origin from the Ostrozhsky family came up with a plan for a union between the Orthodox bishops under Polish rule and the Roman Catholic Church in the 1590s. While he repudiated his support for the plan, the Jesuits and Polish government saw an opportunity to bring the Orthodox faithful of Ukraine into line, and enacted the Union of Brest in 1596. The new Uniate Church was Orthodox in ritual, but Catholic in loyalty. Today it is known as the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church, and has over five million adherents.

The Uniate hierarchs leveraged their support from the Polish government to seize property from Orthodox clergy who refused to join them. The Orthodox Church itself was outlawed, although it was legalized again in 1607. Orthodoxy and its believers found themselves needing a new protector, as did the masses of Rus’ serfs under increasingly oppressive Polish masters. They all found that protector in the Cossacks.

The steppe in what is now southern Ukraine and southern Russia had been largely depopulated since the Mongol invasions, and even the forest steppe was lightly populated into the late 16th century. Few dared to live in the steppe due to the ever-present threat of horse-riding slavers. Among the few were the Cossacks. Originating as Tatar renegades from the Khanate of Crimea who served as mercenaries for Lithuania or Russia, the Cossacks of Ukraine gradually became largely Slavic due to waves of Rus’ peasants fleeing Polish oppression into the steppe.

The Don Cossacks dwelled to the east of what is now Ukraine, in southern Russia and parts of Lugansk. They took advantage of the wealth in fish that the Don River had to offer them. Their home in the early days was the hotly contested frontier between the Nogay and the Crimean Tatars. Depopulated by decades of raiding, it was a rich land for a fisherman who knew how to fight and hide. Their descendants would play a role in many parts of Russian history, most recently in rising up in rebellion against the Ukrainian government in Lugansk in 2014.

The Cossack lifestyle varied. Some lived in fortified free towns under Lithuanian or Russian influence and served as border guards. Others, the Zaporozhian Cossacks, lived south of the Dnieper River Rapids. While romantically remembered as a democratic society, the reality of Zaporozhian Cossack governance was closer to a military dictatorship kept from becoming too oppressive by angry mobs.

While Zaporozhian Cossack relations with the Orthodox Rus’ nobility were usually friendly, they were quite hostile to the great Polish landowners - the magnates. The Cossacks saw themselves as subjects of the King of Poland and did not believe they should be bounded to the Polish nobility or magnates. The Polish kings had become weaker after 1572 since the extinction of the Jagiellon dynasty had turned Poland into an elective monarchy. The new king had to make concessions to various factions of the nobility in order to secure his election, which made it difficult for him to raise money or soldiers. Thus the king found it useful to reach out to the Cossacks directly to find a source of soldiers. To win their support, he could grant or take away their privileges, much to the annoyance of the Polish nobility and the magnates. The Polish nobility feared that the king could use the Cossacks against them, and the magnates resented the Cossack control of good farmland.

The Cossacks fought for their freedom against the encroachments of Polish magnates on a number of occasions in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. While magnate greed was a major driving factor, the Cossacks were not entirely blameless. Those Cossacks not on the king’s payroll regularly raided the Ottoman Empire by land and sea, drawing Poland into expensive conflicts with its powerful neighbor.

The bitterness of the fighting with Turkish Moslems and Polish Catholics drove a renewed commitment to Orthodoxy among the Cossacks. The Cossacks brought a printing press to Kiev in 1615 and printed a number of cultural, religious, and educational texts. Intellectuals from Galicia in the west were brought to Kiev the same year, and it was they who formed a religious brotherhood and new educational system. The intellectuals identified strongly with their patrons, declaring that the Cossacks were the heirs of the Rus’ and that their purpose was to free the Orthodox from oppression. True to their faith, the Cossacks prevented Uniate churchmen from taking office in Kiev and used their influence with the king to push for recognition of secretly appointed Orthodox bishops.

In 1632, the King of Poland died and a new royal election was held. During the election, the Cossacks attempted to win representation in the Polish government as a noble estate. Needing troops for a campaign against Russia, the new king agreed to a compromise, not on the social status of the Cossacks, but on the status of the Orthodox Church. The Orthodox bishops were to be elected by the clergy and nobility, but confirmed by the king. Both the Uniates and the Orthodox were to have a metropolitan in Kiev.

The trouble for the Orthodox was that their previously appointed Metropolitan of Kiev, Isaiah Kopinsky, was viewed as illegitimate along with the other secretly appointed clergy as they had not been confirmed by the king. A rival of the Orthodox but Catholic influenced Metropolitan Pyotr Mogila, Kopinsky and others looked to Russia with a sympathetic eye.

Russia had been gradually recovering from its 1598-1613 collapse, and was looking to renew its expansion. One of its objectives was the destruction of the Crimean Khanate and the subjugation of the steppe. The vast, uncultivated lands of the steppe were still home to roving pastoral nomads who regularly raided the settled peoples for animals, wealth, and slaves. The Russians naturally wanted to put an end to that menace. The subjugation of the steppe meant not just an end to an existential security threat, but also the opening up of the steppe for agricultural exploitation. Some 70% of the Russian population lived north of the forest line. If the steppe was made safe for farming, then Russians would gain great wealth and be able to feed a larger population. The vast armies of conscripts that enabled Russia to defeat Napoleon and Hitler had yet to be grown.

For centuries, the Rus’ had built fortifications on their steppe frontier hundreds of kilometers long. The fortifications were effective in greatly reducing the number of raids from the steppe peoples, and also aided in projecting Russian power. The frontier town of Voronezh was founded in 1585, and Belgorod was founded in 1599. The Russians began to construct a new line of fortifications in 1635 from Voronezh in the east past Belgorod to Ahtyrka in the west.

The fortified lines attracted immigrants and refugees from the Rus’ and Cossacks under Polish rule - among them the maternal ancestors of future Donbass separatist Pavel Gubarev. Those people brought the Cossack system of military and civil administration with them, but were firmly under the control of Moscow. The Russian government organized the population into Cossack regiments based around cities such as Kharkov and Sumy, but also into tax free agricultural settlements meant to attract immigrants.

Orthodox religious figures had looked to Moscow for aid as far back as the 1590s when the Union of Brest attacked the Orthodox Church, and Moscow had answered their pleas. By 1623 Orthodox monks from Ukraine arrived in border towns every year requesting assistance from the Tsar. Some carried messages from the hierarchs in Kiev and Przemysl requesting that the Tsar conquer their land. In time, he would oblige.

The twenty year period from 1640 to 1660 was an unusually tumultuous one. The British Isles fell into civil strife, there was chaos in the Ottoman Empire, the Ming dynasty in China was overthrown by the Manchu, and a third of Poland would die in what would be called “The Deluge”. The Little Ice Age was very bitter in that twenty year span, bringing famine and misery throughout the world. Ukraine too suffered. Bread prices were high in 1638, the cold summer of 1641 led to a sparse grain harvest, spring frosts in 1642 and 1643 worsened the food situation, then plagues of locust in 1645 and 1646 devoured much of what could be harvested.

Nonetheless, the Zaporozhian Cossacks had hope. The King of Poland planned to pay tens of thousands of them for their service in a military campaign. After the Polish nobility rejected the king’s plans, the situation among the Cossacks became explosive. They had nothing to lose. Cossack nobleman Bohdan Hmelnitsky, terribly aggrieved by mistreatment at the hands of the Poles, led a massive uprising in 1648 with the aid of the Crimean Tatars.

While Hmelnitsky initially meant for the rebellion to be to the benefit of the Cossack estate within Poland-Lithuania, it quickly spiraled out of his control. The peasant masses and unregistered Cossacks rose up to slaughter Poles, Jews, and Catholic Rus’ wherever they could find them. In 1649 Hmelnitsky declared himself the “Autocrat of Rus’ by the Grace of God”, showing his intentions of taking what is now Ukraine and Belarus for the nascent Cossack state.

Nonetheless, Hmelnitsky’s diplomacy was more pragmatic. Working with the Crimean Tatars, he wanted to build a grand coalition with the Moldavia, Lithuania, Brandenburg, and England that could force Poland-Lithuania to accept Ukraine (although under the name Rus’ or Ruthenia) as a third and equal state within the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Despite initial successes, Lithuania, Transylvania, and Wallachia rallied against Hmelnitsky. Appeals to the Ottoman Turkish sultan amounted to little, and even his Crimean Tatar allies cut their support. In 1653, Hmelnitsky concluded that only Russia could save him.

The Russians had been reluctant to intervene in the rebellion due to fears of Polish strength as well as due to domestic instability in 1648. By 1653, Russia was in a better position. The new Russian Orthodox patriarch, Nikon, had been in close contact with Rus’ clergymen from Ukraine, and worked with Hmelnitsky’s envoys to pressure the Tsar into becoming the protector of the Cossacks.

In January of 1654 Russian ambassadors met with Cossacks at the town of Pereyaslav. After several days of negotiations, they came to an agreement. The Zaporozhians swore their loyalty to the tsar, the freedoms of the Cossacks were to be preserved forever, the hetman (leader of the Cossacks) was to remained an elected position, the Cossacks were to be protected, and sixty-thousand Cossacks were to be paid a wage by the tsar. The tsar’s title was adjusted after the negotiations were completed. No longer merely the Tsar of All Rus, he was the Tsar of All Great and Little Rus’.

Thus was the beginning of the end of the second tradition of Ukrainian statehood, which had only a few years of fluorescence. Always dominated by either Poland or Russia, the Zaporozhian Cossacks were never truly independent in the way that the earlier Kingdom of Galicia-Volhynia had been. Nonetheless, some of the Cossacks had a concept of national identity independent of both Poland and Russia, as well as a government that claimed to act in an exclusive national interest. That contrasts with Galicia-Volhynia, which considered itself part of a broader Rus’ nation that was not exclusive of the northeastern states such as Vladimir and Novgorod that later became a core part of Russia. However, it should not be forgotten that there was a strong pro-Russian element within the Cossack communities.

Others Cossack leaders such as Ivan Vygovsky and Pyotr Doroshenko carried on the vision of an independent Cossack state, or at least a Cossack state equal to Lithuania and Poland within the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, into the 1670s. While supported by some of the Cossack elites on the Left Bank, class divides led the more egalitarian and Russophilic Zaporozhians remaining in alignment with Moscow rather that the Cossack elites.

Russia and Poland-Lithuania agreed to a truce after thirteen years of war in 1667. The right (west) bank of the Dnieper was left in the hands of Poland, while the left (east) bank was left in the hands of Russia. Kiev, despite being on the right bank of Dnieper, was assigned to Russia. The Orthodox nobility as well as Cossack elites kept and even increased their status in the autonomous Hetmanate under Russian rule. Polish nobles on the left bank had been killed or had fled west, where the ideology of Sarmatianism excluded dual loyalties to Orthodoxy and Rus’ heritage. Whereas Ukrainians had autonomy to various degrees under Russia, they would never regain it under Poland.

The Ukrainians of the late 17th century were thus divided across six administrations: Free (Sloboda) Ukraine, the Hetmanate, Zaporozhye, the Polish palatines, Transylvania, and the Crimean Khanate. The last two were irrelevant - neither the Rus’ sheepherders of Transcarpathia nor the slaves under the Crimean Khanate had much of a historical memory or any political power.

The Polish palatines west of the Dnieper River were ruled by appointees of the king and exploited by a small minority of Polish nobles who administered their lands with the help of a rapidly growing Jewish population. Ukrainians had no representation in Poland after the mid-17th century. They were a largely oppressed nation of serfs, yeoman farmers at best in the depopulated lands closer to the Dnieper. Over the course of the second half of the 17th and first half of the 18th century Orthodoxy declined in Polish-controlled Ukraine. By 1721, all the Orthodox eparchies under Polish rule had become Uniate - tugging the souls of the Ukrainians living under Polish rule towards the West.

In spite of decades of immigration from further west, Free Ukraine was still sparsely populated at the end of the 17th century, with merely 120,000 people in the regimental centers and tax free settlements. Among the regimental centers were Kharkov, Sumy, and Izyum. The Little Ice Age and chaos in The Ruin in the mid-17th century had killed a large part of the Ukrainian population. Nonetheless, the autonomy given to Free Ukraine, the growing prosperity of the tax-free settlements, and the protection from the steppe raiders allowed for the population to grow over the course of the 18th century. In 1773, Free Ukraine’s population had grown to 660,000. In 1765, Russian control over Free Ukraine was solidified and its traditional rights were abolished. As the regimental centers were never united but administered separately by Moscow, there were few protests.

The Hetmanate was the autonomous but Russian-aligned successor to Hmelnitsky’s Cossack state from the 1640s and 1650s. United under one ruler, the Hetman, it maintained its separate identity until its gradual abolition in the 1760s and 1770s under Catherine the Great. The Cossack elites who had struggled to gain recognition as nobles in Poland-Lithuania became a de facto nobility (the Noted War Comrades). While the elites began as a service nobility whose wealth depended on the fulfillment of duty to the state, they quickly became a landed nobility - that is their families could inherit their offices and properties after their deaths. In spite of this, the peasantry was relatively free and retained their freedom of movement for the entire existence of the Hetmanate. The old Polish nobility had been extinguished in Hmenlnitsky’s uprising, so all nobles in the Hetmanate of either Orthodox Rus’ noble or Cossack origin until the 1710s when the Russian government began appointing others such as German immigrants. The Hetmanate was an Orthodox state, and came under the jurisdiction of the Russian Orthodox Church and the Patriarch in Moscow.

While more populous than Free Ukraine, the Hetmanate was sparsely populated by the standards of Russia and Poland. By the time of its dissolution in the 1760s, its population was still barely over a million. Industry and trade had collapsed, and the little of it that was left was run by Greeks who took over the economic niche which had been left by the Jews. In spite of its poverty, the religious and intellectual influence of the Hetmanate on Russia was tremendous. Schools and associations founded by Orthodox Rus’ nobles earlier in the 17th century were far superior to those in contemporary Russia, so their graduates became greatly overrepresented in the highest echelons of Russian culture and religion. As much as 70% of the upper Russian Orthodox hierarchy from 1700-1762 was born in Ukraine or Belarus. While Russia was gradually Russifying Ukraine politically, Ukraine was Ukrainizing Russia culturally.

Zaporozhye was the least populous of the four relevant areas of Ukraine. With a population of merely 184,000 in 1762 (of whom only 34,000 were Cossacks), the region was mostly wild - a frontier between the Moslem Crimean Tatars and Orthodox East Slavs where few dared ride for fear of slave raiders. Xenophobia was the norm rather than the exception in Zaporozhye. They responded with violence when the Hetmanate tried to extend its authority up the Oryol River and Samara River in the 1690s. Even liberation was dangerous when done by Zaporozhians. In one instance in 1675, Zaporozhian Cossacks under Ivan Sirko who had freed 7,000 Christian Rus’ captives from Crimea found that 3,000 preferred to go back to Crimea. He ordered their execution. There was little love between the Zaporozhians and the Crimean Tatars.

With Poland-Lithuania in decline and the Crimean Tatars less of a threat, Russia turned north to face mighty Sweden. Despite a population that was only a little over a million, Sweden had been the dominant power in northeastern Europe for over a century. Sweden ruled the outlets of a number of rivers, thus giving them dominance of the Baltic and enabling them to ship troops and supplies far more cheaply than their enemies. The Swedish government also controlled an unusually large fraction of the economy, enabling it to mobilize power equal to that of far larger states. As with most pre-modern states, the general population’s lack of birth control led to the nation being able to recover from even horrendous battlefield losses - as long as the political structure, transportation network, and agricultural system remained intact. State collapse was worse than even the most costly wars.

The first eight years of the war were fought in the Baltic, Denmark, and Poland. The Cossack Hetman, Ivan Mazepa, while far from the fighting, was required by Russia to send troops and laborers north for the war effort. An old man who had been loyal to the Russian Tsar Peter the Great since 1689, Mazepa faithfully fulfilled his duties. Ukrainians were deeply unhappy with his extensive conscription. With 40,000 Cossacks sent into battle out of a population of a few hundred thousand, most had immediate relatives fighting in a far-away war that didn’t seem to involve them at all. In addition, Russia’s weakness against tiny Sweden made it appear that their servitude to Moscow was unwise.

Across the steppe in the Don River Basin, the Don Cossacks were displeased by Russian oversight of their land. Russian bounty-hunters pursuing fleeing serfs outraged the Don Cossacks, some of whom followed Kondraty Bulavin in a rebellion. Not all of the Don Cossacks rallied behind Bulavin however. The Don Cossacks of Lugansk Village remained loyal to the Tsar, and joined his forces in crushing Bulavin and his rebels.

When Sweden decided to march on Moscow in 1708, one part of their coalition, led by their Swedish puppet Stanislaw Leszczynski, threatened the Hetmanate. Mazepa requested aid from Russia, but Russia refused to send any as they lacked troops to spare. Mazepa considered Russia’s refusal to aid him a breach of the Pereyaslav agreement, thus making the Hetmanate an independent political actor again. When the King of Sweden and his army of Swedes and Germans invaded Ukraine rather than Belarus in 1708, Mazepa had a choice. He could stay true to Russia, or throw his lot with the Swedes.

Mazepa chose to rally behind the Swedes, bringing 4,000 Cossacks with him. While shocked, Peter moved quickly to ensure that Mazepa was unable to rally many behind him. One of his armies razed the Hetmanate’s capital of Baturin and massacred the population. Possible Mazepa sympathizers were arrested, tortured, and executed. Peter then appointed a new Hetman and established a new capital for the Hetmanate. While Mazepa’s Cossacks were bolstered in number with Zaporozhians who were also unhappy with Russian rule, most Cossacks supported their fellow Orthodox Russians over the Protestant Swedes. There was more organic sympathy to Russia among the Cossacks than there was for an independent Hetmanate.

On 8 July 1709 the decisive battle of the Great Northern War was fought at Poltava, in what is now eastern Ukraine. The Swedes, Germans, and rebel Cossacks were utterly defeated by Russia. Cossack officers who had supported Mazepa were charged with treason and executed. The Hetmanate’s autonomy was scaled back, and government officials would watch Hetman closely in the future. Mazepa himself died in exile in the Ottoman Empire two months later. His supporters elected Filipp Orlik as their new leader, signed an alliance with the Crimean Tatars, and won Ottoman support for his claims over Zaporozhye and Right Bank Ukraine. Orlik gained little support in his small campaigns against Russia in Ukraine, in large part due to accompanying Crimean Tatar slavers.

There would be few Ukrainian moves towards independence or national consciousness over the course of the next century in a half. The steppe served as a hiding place for horsemen deep into the 18th century, but the riders had few aspirations beyond banditry. Polish landholders and their Jewish employees were loathed by the enserfed Ukrainian peasantry, and were the main targets of the bandits. The bandits, called Haydamakas, were suppressed by both Poland and Russia.

With the Russian victory in the Great Northern War, the steppe frontier was gradually closed. Russia’s growing strength and successful destruction of the Crimean Tatar capital in 1736 brought an end to the slave trade, crippling the Crimean economy. In 1770 Crimea fell under Russian influence, and it was annexed outright in 1783. Crimean Tatar nobility were incorporated into the Russian nobility, and Islamic clergy were granted more extensive privileges than their Orthodox counterparts. Nonetheless, almost 100,000 Crimean Tatars emigrated to the Ottoman Empire after the Russian annexation of the Crimea. That was just the first wave of Tatar emigrants. The peninsula would be Russified in fits and bursts over the next 162 years. Repeated episodes of disloyalty from the Crimean Tatars led to repeated episodes of brutal reprisals and deportations.

With the southern steppe frontier secured, Russia had no more need for the Cossacks in Ukraine (Cossacks were kept elsewhere). While Serbs, Bulgarians, Romanians, and Greeks had been settling the steppe as early as 1751 under Russian auspices, Zaporozhye would not be fully under Russian control until 1775 when government troops dissolved the political structure. Some Zaporozhians were pressed into military service, others were left as free farmers. A new province, New Russia, was created that included much of southern Ukraine and included Zaporozhye. Protestant Germans and Russians joined the existing settlers and formed a new culture that while part-Ukrainian, was part-alien too.

The Cossack elites were integrated into the Russia on good terms. Military units that had once been frontier auxiliaries were turned into professional formations. Post offices eased communication and schools spread advances in culture and technology. Most important however was the expansion of serfdom. In 1783 Catherine the Great forbade about 300,000 peasants from leaving their residences and obligated them to provide free labor for the nobles who owned the land they were on. For most Ukrainians, the advance of Russian rule was synonymous with the spread of serfdom.

The failure of the Polish-Lithuanian government to solidify its authority over the nobility in the 16th century had been a mere problem when it was stronger than all of its Christian neighbors, but by the 18th century it was an existential issue. Foreign governments openly intervened in Polish elections and the nobility, favoring a weak government over a strong one, refused to allow reforms. Poland-Lithuania was divided in 1772, 1793, and 1795 between Prussia, Russia, and Austria.

At the end of the partitions of Poland, Russia had almost completed its dream of reunifying the lands of medieval Rus’. About 85% of Ukrainians fell under Russian rule, while the remainder fell under Austria. The partitions of Poland also aided Russia’s absorption of its Ukrainian territories by securing the entire length of the Dnieper River. Navigable from Smolensk to the rapids well to the south of Kiev, the Dnieper served as a highway for the Russian Empire, enabling faster communication and cheaper shipping, thus further integrating the Empire.

While both Russia and Austria supported the local Polish nobility over Ukrainians in Right Bank Ukraine and in Galicia out of aristocratic solidarity, history was moving towards mass movements. Poles had rallied behind Napoleon against both Austria and Russia before his defeat, but even then the old order still valued the connections of the cosmopolitan aristocracy over national mobilization. It was only after the Polish revolt of 1830-1831 that Russia decided that the Polish aristocracy under its rule was unreliable. By contrast, the Austrians faced a number of minor rebellions by starving Ukrainian peasants in Galicia in the 1820s and 1830s that delayed a government push against the Polish aristocracy until 1848.

Elite cooption in Russia and outright lack of elites in Austria as well as widespread illiteracy and absence of explicit national political structures prevented the development of Ukrainian national consciousness in spite of a dialect continuum that cross the Austrian-Russian border. In 1842 only 15% of children in Galicia attended school, and as late as 1865 only 4.5% recruits from Galicia could read. The situation across the border was likely worse. The Russian government saw an opportunity in that lack of education to acculturate Ukrainians from their folksy culture into a more sophisticated Russian culture through the foundation of a number of universities in Ukraine. Under of the guidance of Sergey Uvarov, the universities studied Ukrainian history to determine a path forward in the assimilation of Ukrainians.

The result was the concept of a Little Russian identity. It emphasized the shared heritage of the Great Russians with the Little Russians that went back to the medieval Rus’ realm, as well as their shared Orthodox faith and their shared struggles against the Poles, Turks, and Tatars. The Little Russian identity was to be a regional identity inclusive of a broader Russian identity.

In contrast, an exclusive and anti-Russian Ukrainian identity was forming among small but independent circles - most famously including the poet Taras Shevchenko. Deeply opposed to Russians, Germans, Jews, and Poles, Shevchenko saw (not unreasonably) Catherine the Great as the destroyer of Ukraine. He believed in the abolition of serfdom, glorified the Cossacks, and opposed the monarchy.

While the competing Ukrainian and Little Russian identities grew with the economy and population in Russian-held Ukraine, the Ukrainian national awakening proceeded along different lines in Austrian-held Galicia. About half the population of Galicia was Polish and the other half was Ukrainian in 1849. Both were Catholic, although the Ukrainians practiced the Uniate or Greek rite of Catholicism while the Poles practiced Roman Catholicism. Although Ukrainians in Galicia called themselves Rusyny or Ruskyi (close to the Russian endonym of Russkiye), the Austrian government determined that they were their own ethnicity - the Ruthenians.

There was a wave of liberal and nationalist unrest in Europe in 1848. Galicia too was affected by it. When the Polish nobility in Lvov heard of the revolution in the Austrian capital of Vienna, they demanded autonomy for Galicia, some hoping that was the first step to a revived Polish state. However, Polish nobles in eastern Galicia were worried that the actions of urban Polish democrats would start a murderous social revolution. They ruled over a mass of impoverished and starving Ukrainians who had revolted as recently as 1846. The Austrian governor, Franz Stadion, decided to emancipate the serfs of Galicia with compensation for landlords. Thus winning the support of the majority of the population in Galicia, Stadion had a free hand to crush Polish rebels.

While Ukrainians had little political representation in Galicia in 1848, they did have religious leadership who could advocate for their interests. Lvov’s Bishop Yahimovich proposed in 1848 that Galicia be split between a western Polish Galicia and an eastern Ukrainian Galicia. With the backing of Governor Stadion, Bishop Yahimovich founded the Supreme Ruthenian Council and the first Ukrainian language newspaper. The Supreme Ruthenian Council declared that Ruthenians (Ukrainians) were part of a great people fifteen million strong, of whom only two and a half million lived in Galicia. That is, they claimed the entire Ukrainian people as their own, even outside of the Austrian Empire. The Polish nobility were extremely displeased by rising Ukrainian national consciousness. They denied that Ukrainians were a people, but merely Poles who practiced the Greek rite of Catholicism. The Poles created a Ruthenian Council to rival the Supreme Ruthenian Council, and argued in the council newspaper that it was the true representative of Ukrainians, as well as that Poles and Ukrainians should work together as friends. Governor Stadion was blamed for inventing Ukrainians by more than just contemporary Poles. Russian irredentists and separatists today also claim that the Ukrainian identity was an Austrian plot to undermine the Russian Empire.

Nations can be made and unmade. Had things gone otherwise the Ukrainian population in Galicia could have been turned into Poles and the population in the rest of Ukraine turned into Russians. The linguistic differences were not great, the blood of their neighbors not too different, and more importantly there was no literate elite whose status relied upon representing the enserfed masses. Conversely there were nations that could have been born but were not. The Kuban Cossacks in southwestern Russia had their own political system, identity, and dialect. They fought twice for independence, the first time with the White Movement 1917-1920 and the second time with the Axis powers 1942-1945. They lost both times and were culturally extinguished.

Ukrainians in Galicia, while somewhat sidelined by the Polish nobility even after 1848, remained participants in civic life. As a peasant people excluded from the nobility, they saw their national and social struggles as one and the same. As the 19th century went on, they advanced in culture. A Ukrainian language department was opened at Lvov University. Two volunteer military units were formed, loyal to the Austrian Emperor. And three distinct national movements split from each other: the Russophiles, the Ukrainophiles, and the Polonophilic Old Ruthenians.

While the 1840s and 1850s had featured interest in Saint Petersburg into the Ukrainian language, it came to be seen as dangerous in the 1860s - after the defeat in the Crimean War and the emancipation of the serfs. In 1862 the Russian government issued the Valuev Decree which censored Ukrainian-language publications. In 1875 the Ems Decree went further and banned importation of Ukrainian language books, performance of Ukrainian plays, and use of Ukrainian in musical lyrics. The official position of the Russian Empire was that the Ukrainian language and nationality did not exist. Such was not an unusual attitude at the time, with the French in particular suppressing all regional languages within their own highly centralized country.

Ukraine’s industrialization shaped the national attitudes around the country. The steppe lands of the south and east were settled by many Ukrainian farmers who grew rapidly in number, but Russians and others such as German Mennonites settled the steppe too. Due to differences in landholding practices Russians were much more likely to settle in cities than Ukrainians. In addition, many Ukrainians who moved to cities adopted the Russian language, culture, and identity as they had a weak sense (if any) of their own identity. In 1897, Ukrainians outnumbered Russians six to one in Ukraine, but their numbers in the cities were about even. Kiev and Kharkov were majority Russian, and Russians were almost a majority of the population of the highly cosmopolitan port of Odessa.

By the early 20th century, Ukrainians were breaking into mass politics. In Galicia, intensely anti-Russian Ukrainian National Democratic Party dominated the Ukrainian vote. They aimed to divide Galicia into Polish and Ukrainian halves before becoming independent. Both the Polish nationalists and Polish socialists were deeply hostile to the Ukrainians in Galicia. Electoral law benefitted the Polish nobility, which kept its hold on the regional legislature even after the 1907 election. Several people died in clashes, and ethnic relations worsened after a Ukrainian assassinated a Polish official in 1908. The Polish-Ukrainian conflict, by that point 567 years old, was set to explode and would in time.

The Russophiles within Galicia comprised perhaps only a tenth of the Ukrainian population there. While funded by the Russian government and deeply involved in the Orthodox Church, Russophilia was more popular in the neighboring region of Transcarpathia - under Hungarian rather than Austrian rule. The descendants of those Russophiles would later play a role in the Donbass region.

It was the 1905 revolution that opened up the politics of Russian-held Ukraine - as well as a wave of terror. Censorship was relaxed, and the first Ukrainian language newspapers appeared. Their circulation was limited - only 20,000 combined in 1908. Two fifths of elected deputies from Ukraine were socialists, although renewed oppression forced them underground again in 1908. Russian nationalism did very well in Ukraine - the nationalist Union of Russian People had its largest branch in Volhynia in western Ukraine. Animosity against socialists, Jews, and Poles played a major part of their success.

The First World War laid the groundwork for the Second and much more. Vast armies clashed, men and materiel were massed in unprecedented concentrations, nations were born, and millions of people died. Ukraine too, was a battleground. The Austrians arrested Russophiles in Galicia immediately after the beginning of the war. 20,000 of them were taken to the concentration camp of Theresienstadt. Those who escaped Austrian persecution, or who hid successfully until the Russian army arrived, were appointed to administer Galicia in the name of the Tsar. When the Austrians and Germans retook Galicia in summer of 1915, the remaining Russophiles fled eastwards. They were resettled into the Don River Basin. Some of their descendants remain there even today under the Donetsk People’s Republic.

The democratic government that succeeded Tsar Nikolay II after the February Revolution of 1917 did its best to maintain the front against the Germans and Austrians. However, the total collapse of the government in the Bolshevik Revolution later that year led to the collapse of the front as well. Ukraine disintegrated as well, and was feuded over by a number of factions until 1921. The Bolsheviks, Don Cossacks, and the Poles are the most relevant. The Bolsheviks were organized into three groups, one based in Kiev, one in Kharkov, and the last and smallest in Odessa.

The Bolsheviks in Kharkov proclaimed the Donetsk-Krivoy Rog Soviet Republic, and took an explicitly anti-national understanding of territory. Instead of language or ethnicity determining the borders of the state, they were instead to be based off of economically self-sufficient regional units. In their case, that economically self-sufficient regional unit was to be the heavily industrialized Donets River Basin and some adjacent economically integrated territory which included Kherson, Rostov, Taganrog, Novocherkassk, and Yekaterinoslav (modern Dnipropetrovsk). Industrialists had proposed the unity of what became the DKR as early as the 19th century - uniting the former Tsarist governorates of Yekaterinoslav and Kharkov with the western parts of the Don Cossack lands.

Ultimately, the DKR was dissolved under Lenin’s orders. He wanted a large Soviet Ukraine rather than a small one so as to better organize and coordinate military resources. Additionally, Soviet leadership was concerned about Great Russian chauvinism, and believed that fracturing the former Russian Empire into a number of smaller Soviet republics would insure that it was no longer a problem. DKR leadership such as Fyodor Sergeyev as well as a number of central Soviet politicians like Georgy Pyatakov and Nikolay Buharin objected, arguing that a separate Soviet Ukraine would have counterrevolutionary or separatist tendencies. As Marxists, they believed self-determination was only an aspiration of the working classes rather than a fictitious national will.

Sergeyev and the DKR influenced a number of contemporary Russian irredentists. Russian right-nationalist writer and foreign volunteer Alexander Zhuchkovsky quoted him approvingly in his opposition to Ukrainian separatism. Donetsk People’s Governor and left-nationalist Pavel Gubarev is in a sense his spiritual heir as he too sees the industrial Donets River Basin and New Russia as a natural industrial center that should not be chained to Ukraine.

Opposed to the Bolsheviks in the Donbass were the Don Cossacks. Whereas Russian-speaking urban populations (including those in the heavily industrialized Donbass) had many Bolshevik sympathizers, there were few among the rural Cossacks. Widespread landownership and fear of restive Russian tenant farmers who had been migrating to the Don River Basin for the previous thirty years inoculated many of the Don Cossacks against communism. One Don Cossack, Vasily Chernetsov led anti-communist forces (including Cossacks) as well as military cadets (a quarter of them Jews) against the Bolsheviks in the Donbass. While initially successful, they were heavily outnumbered and eventually absorbed into the Volunteer Army.

In the aftermath of the Russian Revolution and Civil War, the Bolsheviks enacted a De-Cossackization policy. Many Don Cossacks were killed, all suffered, their political structure was abolished, and their home was divided between Soviet Ukraine and Soviet Russia within the Soviet Union. Nonetheless, their memory survived in some minds. When Lugansk Village rose in rebellion in 2014 against Ukraine alongside the rest of the Donbass, it flew the flag of the Don Cossack Host rather than that of the Lugansk People’s Republic or Russia.

Soviet Ukraine was independent in theory between 1920 and 1922, only bound to Soviet Russia by a treaty of alliance. However, in practice Ukraine was administered by the same Bolsheviks who ruled Russia. Formal political union took place in 1922 when the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics was formed. Russia, Belarus, Ukraine, and the Transcaucasus were the original union republics underneath the USSR. While nominally a federal system, the 1924 constitution placed all political and economic authority in the hands of the central government. Nonetheless, there would be movements both towards greater integration as well as greater autonomy throughout the Soviet period.

In 1920 there were three communist parties in Ukraine: the largely urban Russian Bolsheviks, the largely peasant Ukrainian Borotbists, and the Ukapists. The Bolsheviks (literally “Majoritarians”) and Borotbists (literally “Strugglers”) were about equal in number (15,000) in 1920. Lenin had the Ukapists and Borotbists dissolved in March 1920 after turning down their applications for entry into the Communist International. Many Ukapists and Borotbists joined the Bolsheviks.

In spite of the absorption of the Borotbists and Ukapists, the Ukrainian Bolsheviks were still a largely foreign party in 1922, with 77% of members being non-Ukrainian. Recognizing their weak roots in the Ukrainian countryside, the Bolsheviks launched a Ukrainianization drive in 1923. The school system was shifted to Ukrainian, Ukrainian use was expanded in the universities, bureaucrats were required to take Ukrainian lessons, Ukrainian newspapers were founded, Ukrainian language signs were made, and Ukrainians were promoted in the party apparatus. Not only was the aim to strengthen communism within Ukraine, but also to attract the support of millions of Ukrainians living under Polish rule in Galicia. World Revolution after all could not be stopped by mere borders.

While Ukrainization was advocated by the Soviet government, there was widespread passive opposition to Ukrainization policies in the Russian majority cities of the east. The Russian language continued to dominate within urban industry, and Ukrainian speakers rapidly adopted the Russian language upon moving to the eastern cities. Fewer than 10% of workers in the Donbass in the 1930s knew Ukrainian, and it was a minority language among workers in Kiev and Kharkov. Ukrainians and Russians largely saw each other as part of the same ethnic majority and mixed with little problem. Some 6.5 million Ukrainians lived in Soviet Russia in 1925, and their descendants today are fully assimilated Russians.

Ukrainianization funding was cut in 1928, allowing for institutions to ignore Ukrainianization measures. Odessa, Nikolayev, and Kharkov all moved to reverse parts of Ukrainization measures. However it was the failure of collectivization and the resulting famine in 1932 that turned the Soviets decisively against Ukrainization. Polish spies and Ukrainian nationalists were blamed. The theory was that former members of the Ukrainian People’s Republic (an anti-Bolshevik state based out of Kiev that had been defeated in 1921) as well as Polish agents had successfully infiltrated the communist apparatus through the Ukrainianization process, then sabotaged Soviet agriculture. 16,000 were arrested in this prelude to the Great Terror.

Ukrainianization policies and supporters were further undermined by public Nazi support for an independent Ukraine in 1933. By 1934, Stalin decided that both Great Russian chauvinism and local nationalisms (such as that of Ukraine) should be dealt with on a case-by-case basis, thus removing the last basis for Soviet support for Ukrainianization. Russification was revived outside of primary schools. While a greater share of Ukrainian students studied Ukrainian in primary school in the late 1930s and after than they did during the 1920s at the height of the Ukrainianization movement, Russian supplanted it elsewhere.

Poland had seized the whole of Galicia and half of Volhynia in the chaos following WWI. Naturally favoring its own people over the Ukrainians, Poland gave its army veterans land in the east while also encouraging Ukrainian emigration. The Ukrainian language was excluded from public use, the ethnic label of Ukrainian was never used (Rusyn was used instead), and tribal distinctions were encouraged. Lemkos, Boykos, and Hutsuls as well as Old Ruthenians were encouraged to identify themselves as separate from Ukrainians.

Ukrainian resistance against Polish rule was less common but better known than Ukrainian resistance against Soviet rule. This is partly due to the mercilessness of Soviet reprisals, but also the charisma of Stepan Bandera. Leader of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN), Bandera organized assassinations of Polish and Soviet officials in the 1930s in revenge for the injustices committed against Ukrainians. Sentenced to seven life terms in Polish prison, Bandera escaped in September 1939 during the collapse of the Polish state.

Soviet troops occupied the eastern parts of Poland in 1939 per an agreement with Germany. Galicia fell under Russian rule for the first time in history. The Soviets sought to win local Ukrainian support by Ukrainianizing the school system and abolishing Polish cultural institutions. Additionally, they shifted the ethnic balance of the region in the favor of Ukrainians by deporting over 400,000 Poles.

The Second World War devastated Ukraine. Much of Ukraine’s infrastructure and housing was destroyed in the fighting, 4.1 million civilians died, and 1.4 million soldiers were killed. Much as in 1709, the vast majority of Ukrainians fought alongside Russians rather than the Westerners. Of those who did not fight alongside the Russians, about 250,000 fought for Germany and another 100,000 fought under the banner of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army. The latter, sometimes backed by Germany, sometimes not, killed between 60,000 and 90,000 Poles in Galicia and Volhynia, causing the surviving Poles to flee west.

Thus the Polish-Ukrainian conflict which had begun in 1340 had finally been resolved in WWII. While the centuries of violence have not been forgotten, they have been forgiven. The lack of an active dispute between Ukraine and Poland has led them to peace and mutual affection. The Ukrainian nationalists, no longer occupied with the Polish problem, thus turned their full attention to the Soviet and later Russian problem.

In Crimea, the local Tatars collaborated with the invading Germans at a rate unmatched elsewhere in the USSR. As many Crimean Tatars volunteered to fight for Germany as fought for the USSR. Widespread collaboration caused the Slavs (both Russian and Ukrainian) to loathe the Crimean Tatars as collaborators. The entire Tatar population was deported after the peninsula was liberated by Soviet forces, turning it into an almost purely Slavic land. Even though Crimea was 71% Russian, it was turned over from Russia to Ukraine in 1954 as a gift.