The bus pulled into Kazan Passenger Station – the main bus and rail station in Kazan, capital of Tatarstan. Sitting in the front seat, I was the first to walk out onto the sidewalk and into the cold day. The sky was overcast, the temperature just below freezing. Masses of people milled around. All were clad in the cheap synthetic jackets so popular in that part of the world. The men favored darker colors – black, dark gray, and dark blue, while women favored lighter – pink, light gray, and light blue.

The station had an unusual style. It was a two story building that had been built over 120 years ago under the old empire. Like many buildings in those days, it was made of red bricks. Flowery white crosses decorated the outer walls, and false arrow slits sat beneath pseudo-crenellations in an almost late medieval style. It sat at odds with all of its neighbors, which had been constructed in other styles with straight walls, large windows, and metal girders. A relic from a different age, but a useful one, as the masses crowded inside to escape the cold and buy their train tickets.

As a tourist, I knew little of the customs of this land. I drew out my phone to get a taxi from an app, only to see the charge rapidly plunge. Iphones were not made for the cold. And this land, Tatarstan, was cold.

It had once been much colder. In the last Ice Age, glaciers covered Scandinavia, the Baltic, and much of northern Russia. Tatarstan, in the east of European Russia, was then part of the great tundra-steppe. The tundra steppe reached from Spain in the west across Europe, through Tatarstan, into Siberia, all the way to China. Giant beasts grazed on the grasses, shrubbery, and herbs of the tundra-steppe; among them the woolly mammoth, the woolly rhinoceros, the musk ox, bison, reindeer, steppe lions, giant elk, and the wild horse.

Neanderthals roamed Ice Age Tatarstan too, hunting the great beasts, and in turn hunted by some of them. During the third great expansion of man, they were extinguished - pushed into marginal lands that could not sustain them or exterminated by their more numerous rivals. Races of men followed them, and each was swept away by their successor. Tatarstan was not a forgiving land.

As the world warmed, man moved. A collection of peoples called the Ancestral Northern Eurasians by population geneticists reigned from the Yana River in Siberia deep into Central Asia. A group descended in large part from them, the Eastern Hunter-Gatherers, colonized Tatarstan in the 10th millennium BC. They spread, likely following the paths of rivers, across European Russia.

Organized in small, mobile bands, the Eastern Hunter-Gatherers, or EHGs, quickly fragmented. This is well reflected in their material culture, which was already quite diverse in the mid-9th millennium BC despite genetic homogeneity. The climate of European Russia, including Tatarstan, could not support dense populations capable of transmitting their culture across even moderate distances.

Tall, and with dark features, the EHGs reigned across European Russia for millennia. They were not a stagnant people. Undoubtedly mighty chiefs and tribes rose and fell many times over the millennia, their memories now obliterated by a long list of successors. One great shift in their culture is known. In the 5th millennium BC, the culture of most of the EHGs suddenly became materially identical for the first time in over four thousand years. Technological changes and ecological adaptations had enabled the EHGs of the Comb Ceramic Culture to grow beyond what their primitive ancestors had been able to. Trees were cultivated for their nuts, fish were caught in river weirs, and harpoons were used to slay sea mammals. With all of the extra food from these new technologies, the Comb Ceramic EHG population grew exponentially for a time, and its wealth and population enabled its culture to spread through the EHG lands and beyond. Due to this new wealth, trade expanded. Amber from the Baltic traveled through the EHG lands of European Russia to the people of Caspian. The peoples across the Ural Mountains also traded with the EHGs – their artifacts are found in the Ob River Basin of Siberia.

The range of the Comb Ceramic peoples

Like all peoples past and present, the EHGs would not reign forever. It would be their cousins to the south who would destroy them. Thousands of years before the rise of the Comb Ceramic people, EHGs further south on the Volga River came in contact with a group of people from the Caucasus who had migrated north after the melting of the glaciers. The EHGs overcame these Caucasians, slew the men, and took the women. From them descend the famous Indo-Europeans.

Originally marginal people, the Indo-Europeans stayed close to the Volga and Don rivers for water and food. There, they became among first groups of men to learn how to ride horses. Poor and impoverished, a group of them rode west for the wealth of the Old European civilizations around 4000 BC. There, they devastated much of the eastern Balkans. Towns were sacked, their inhabitants slaughtered, their wealth plundered and brought to their new camps in the Danube River basin. This was to be a preview of the much greater invasions that would come a thousand years later.

Around 3300 BC, the Indo-Europeans still on the steppe changed their lifestyle into what is now known as the Yamnaya (or Pit-Grave) Culture. They began to milk horses, goats, and cows. Unable to drink the milk, they turned it into yogurt or fermented it for consumption. Now the grasses of the steppe could be turned into a useful source of food and drink, and the Indo-Europeans could expand far beyond their camps on the river. Their realm and population both grew.

As their population grew, so did their contacts and explorations. Around 3000 BC they found a massive source of copper in the southern Ural Mountains. Using techniques they learned from their Caucasian neighbors to the south, the Indo-Europeans intensively mined that copper deposit. This greatly enriched the Indo-Europeans, and gave their smiths the materials they needed to outfit entire armies of conquest.

Between 3000 and 2800 BC, the Indo-Europeans overran the Old European civilizations from Ukraine to the Netherlands. Cities were destroyed, forests burned for pastureland, and entire regions depopulated. Some of the survivors joined bands of Indo-Europeans who went back home to the steppe. It is one such group of returning Indo-Europeans who settled in Tatarstan and the surrounding regions. They are named the Fatyanovo-Balanovo Culture by archaeologists.

Arriving in horse-drawn wagons, the Fatyanovo-Balanovo Indo-Europeans were utterly merciless to the native EHGs. The Fatyanovo-Balanovo people show no signs of an infusion of EHG blood, and the EHG cultures retreated with their advance, some fleeing to the Arctic. The new conquerors of Tatarstan brought cattle, pigs, horses, and sheep with them – introducing the lifestyle of their steppe ancestors to the middle Volga River and the Kama River. While they knew of farming, Tatarstan was too cold for the crops they had. Foraging remained a major part of life in the region for the 3rd millennium BC.

Different groups of Indo-Europeans would rule Tatarstan for most of the next 3000 years, rotating through a cycle of mostly Iranian-speaking tribes. Some are known even to history, as the Scythians and Sarmatians noted by Greek and Roman authors. Despite their defeats to later invaders as well as the assimilation of exotic groups from the north and east, the Indo-Europeans who settled in Tatarstan and the surrounding regions still comprise over three quarters of the ancestry of modern day Volga Tatars.

Volga Tatars comprised about half of the milling crowd around Kazan Passenger Station. Their features varied greatly. Some could have been confused for Swedes. Others, for Mongols. But most were in between, the modal Tatar looking like a vaguely exotic eastern European, though with noticeably higher cheekbones.

I walked across the snowy square to a line of taxis and found a Tatar taxi driver. A friendly old man, he told me that it was 500 rubles to go anywhere in the city. I gave him my hotel information, and we drove away. He was quite friendly, and had politics typical of his generation. He told me of the prosperity of the Soviet Union, the fascist coup in Ukraine, and how he shook his head in sorrowful understanding at the extreme wealth inequality in my home city of Los Angeles. LA’s homeless camps had apparently made Tatar news.

I paid little attention to our surroundings during the short taxi ride, but one building was unmistakable. “HOTEL BULGAR” shined out from the building’s central tower in neon-blue lights in English, while the identical Russian name was smaller and lower on the wall over the entrance. The hotel’s name “Bulgar” was a reference to a people that once ruled Tatarstan.

The Bulgars were originally a Turkic people, related by language and identity to Anatolian Turks, Kazahs, Turkmen, Azeris, Uzbeks, Uyghurs, Chuvash, and Yakuts. 2,000 years ago, they were related by blood as well. The original Turkic tribes lived on the eastern steppe under the rule of the mighty Xiongnu steppe confederation.

The origins of the Xiongnu are mysterious, but artifacts, records, and DNA studies have confirmed that they ruled many different peoples. Some are still around today – the Mongols and the Tungusic peoples of the east, as well as the Ossetians of the norther Caucasus. Others are not.

The Xiongnu engaged in a struggle with the Chinese states and empires for centuries, driving both to greatness. Their struggle drove both steppe and settled peoples to improve their societies, lest they become weak and fall to their hated foes. It was centuries after the Xiongnu had splintered into several successor states that the first of the Turkic peoples rode to the west.

Nomads with mutilated skulls riding on shaggy ponies, clad in lamellar armor, and armed with composite recurve bows, the first Turkic people to ride into Europe terrified the mighty Roman Empire in the 4th century AD. They were the Huns, and they would be followed by others over the succeeding centuries. The Bulgars are first noted in Roman histories as arriving in Europe in 480 AD, a century after the Huns. Allying with the Eastern Roman Emperor Zeno, they waged war against the Germanic Goths.

Suffering defeats at the hands of the Germanic peoples and Avars, the Bulgars fade from history for a part of the 6th century. In the middle of the century, they are noted to have been active in the marten fur trade and being divided into a number of tribes of uncertain relationship. In the middle of the 7th century, with the waning of Avar power and the collapse of the Western Turk Khaganate, the Bulgars rose again. They founded Old Great Bulgaria in what is now modern Ukraine under the great Khan Kubrat. It was not to last.

Despite its vast lands that included much of Hungary and the north Caucasus, Old Great Bulgaria was defeated by another Turkic tribe, the Khazars, around 650 AD. Kubrat’s sons scattered west, north, and south with their followers. Asparuh invaded the Balkans with a largely Slavic following and founded Bulgaria. Kotrag fled up the Volga River into Tatarstan. Other Bulgars fled to the north Caucasus with other Slavs in an unrecorded migration which is known only through the name of the Balkars and unique Y chromosomal lineages passed down from father to son.

Kotrag’s followers created the realm of Volga Bulgaria in Tatarstan. Inhabited by a number of different Uralic-speaking tribes related to modern Udmurts and Mari, the Bulgars established themselves as a new ruling class. It was hard for them to extract wealth from the region. Their Uralic tribal subjects retreated to forests where their pigs could feed themselves, and where they could escape the collectors of tribute. The Bulgars remained on the steppe with their herds of cattle, ever vulnerable to the still present Khazars. The Volga Bulgars lacked true sovereignty, and remained vassals of the Khazars until the 9th century.

To the west of Volga Bulgaria, a new power was rising. Vikings had united a number of Slavic tribes and formed the Rus’ – the ancestors of the Russians, Ukrainians, and Belarusians. They were capable sailors and soldiers, and warred with their neighbors. During a period of unrest in the Khazar realm on the steppe in the 830s, the Rus’ began to dispute Khazar claims. The Khazar-Rus’ struggle would continue for about 130 years, and ended in the complete destruction of the Khazars.

The Volga Bulgars were freed by the collapse of the Khazars, but soon faced the Rus’ themselves. Rus’ leader Vladimir the Great launched a campaign against the the Bulgars in 985, building forts along his path to secure his conquered territory. Rather than reduce the Bulgars to a tributary, Vladimir instead signed a peace treaty with them, allowing the Rus’ to sail down the Volga River unmolested. While there would be periods of intermittent conflict, the peace largely held for the next century.

The Bulgars built their capital along the Volga River just 30 km south of its confluence with the Kama River. From there, they could collect river transit tolls to fund their government. They were successful, and leveraged their wealth as a center of trade to consolidate the surrounding Uralic tribes into the realm of Volga Bulgaria.

The furs, waxes, and hides that the Bulgars collected as taxes or tributes from their Uralic subjects were sent down the Volga River into the Caspian Sea. From there, they were taken to Iran or Samarkand and connected to the great Eurasian trade networks. In return, the Bulgars received received silver and cloth. With the silver also came Islam. A sizeable number of Muslims were already living in Volga Bulgaria at the time of Ibn Fadlan’s embassy in 922 AD. Fadlan was disgusted by the Bulgars’ poor practice of Islam. Nonetheless, the Bulgars had converted – officially in 922, and Tatarstan has been a predominantly Muslim region ever since.

In the 11th century, the realms of the Rus’ and Volga Bulgars consolidated and grew closer to each other. This caused strife between once peaceful neighbors. Rus’ pirates on the upper Volga and the Oka Rivers preyed on the shipping of the Bulgars and their trade partners. The Bulgars complained to the Rus’ princes that were supposed to enforce keep the peace of that region. When the Rus’ failed to take action, the Bulgars invaded the Rus’ to deal with the pirates themselves in 1088. Angered by the Bulgar invasion, the Rus’ fought back. Decades of raiding and warring between Volga Bulgaria and the Rus’ ensued.

The conflict was not a total struggle, but the Rus’ were able to make steady gains in land over the Bulgars. Blessed with a warmer climate, more productive soils, and a larger population, the Rus’ steadily drove east. By 1205, the Rus’ realm of Vladimir-Suzdal controlled the Volga River to the confluence with the Oka River. The Rus’ founded the city of Nizhniy Novgorod there in 1221, cementing their control of the confluence, and denying the Bulgars passage further upriver. Further north, the foundation of Ustyug hurt the ability of the Bulgars and their subjects to collect the furs and hides they needed for export. Both the Bulgars and the Rus’ were ignorant of a rising power to the east that would lay both low.

Unified by Chingis Khan in 1206, the Mongols were one of the last but greatest of the steppe conquerors. Many stood against them, but few remained unbowed. Central Asia and Iran fell to the Mongols by 1221, as had parts of northern China. Unsatisfied with their new subjects, the Mongols launched three invasions of Volga Bulgaria, the first 1223, the second in 1229, and the third in 1236. The Bulgar cities were destroyed, their capital twice. Most of the population died, some from the merciless treatment the Mongols inflicted upon them, others from the chaos that accompanied the collapse of the state.

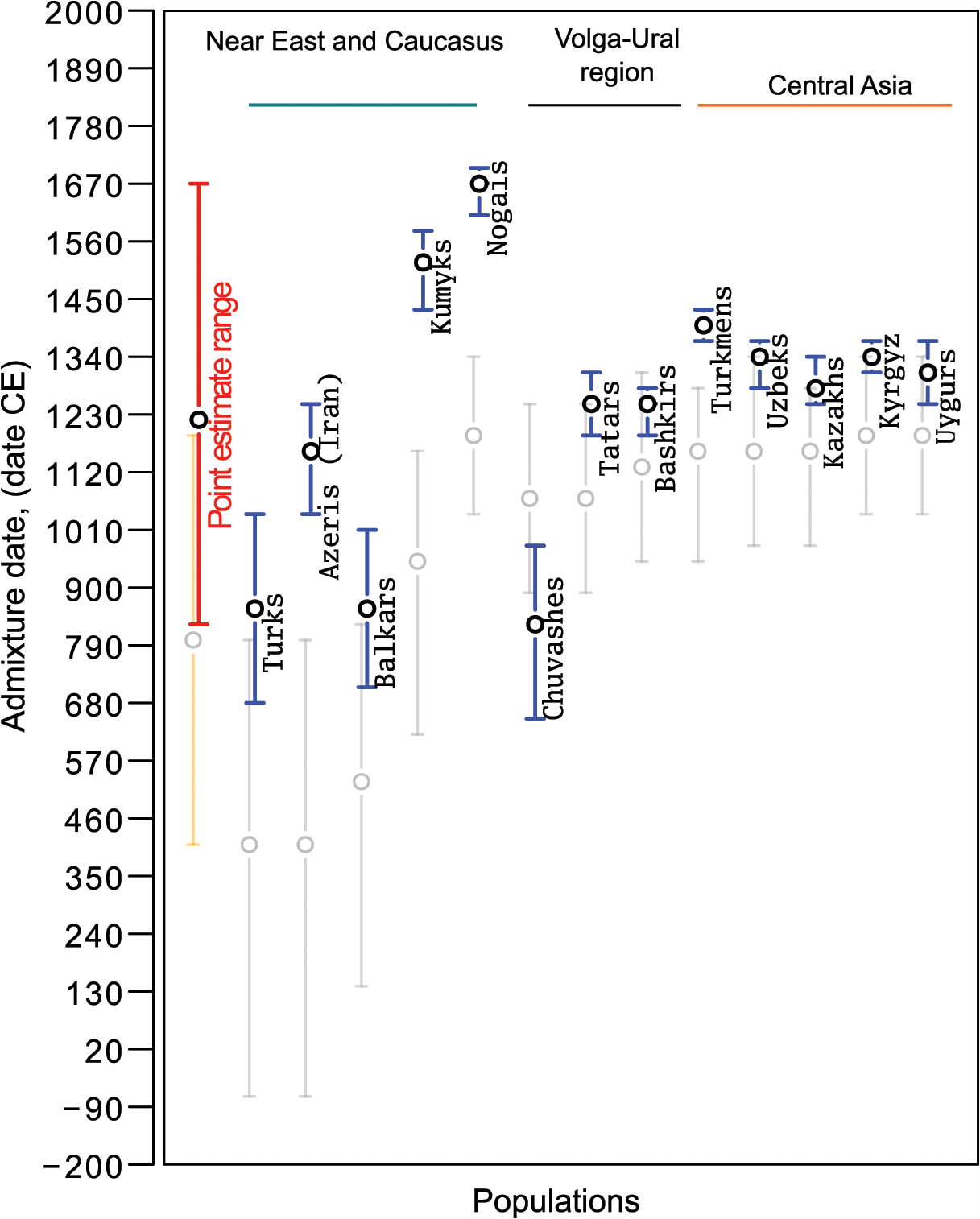

Recent DNA studies of the Tatars have shown that their Siberian and Asiatic ancestors mixed with their Indo-European and Uralic ancestors in the 13th century – the same time as the Mongol invasion, and six centuries after the initial migration of the Bulgars to the middle Volga. The Bulgars made several attempts to restore their lost realm, but they failed. Little of their blood runs in the veins of the Tatars, though the Chuvash to the west of Tatarstan can honestly claim the Bulgars as being among their ancestors.

My hotel had a lavish interior, and the guests fit in well with their surroundings. They were well dressed and looked healthy. The obesity and ill health that have unfortunately become the norm for residents of the United States were rare in Kazan, as in the rest of urban Russia. Half of the guests looked Russian – the round Slavic face, thin hair, and fair features betraying their ancestry. The other half of the guests were also speaking Russian, but had a great range of features characteristic of peoples across the northern half of Eurasia mixed and matched in combinations unusual to a Westerner. The latter half of the guests were a living reminder not just of the population movements that occurred under the steppe conquerors, but also of more recent assimilations of peoples who shared similar ancestry (though in different fractions). If the Tatars are a relic destined to be absorbed into the mass of Russians, they were a new relic that could have entered modernity on their own terms had things gone slightly differently. The ability to assimilate others demonstrates a cultural dynamism capable of growing into something greater.

I checked in with the Russian receptionists, went to my hotel room, and dropped off my belongings. I proceeded back outside to explore the city on the foot. The road I walked along was named Schmidt Street. Hundreds of thousands of German colonists had settled in Russia in the 18th and 19th centuries, many settling along the Volga. While their main settlements were further south, there had been Germans in Kazan too. Later in the day I came across a German Lutheran church.

Intent on seeing the castle, I continued west through the light snow, passing through a park. Locals walked by, all in their synthetic jackets. Far from a grim and run down city, the buildings were well maintained and built in an aesthetically pleasing style. The next street was Butler Street - named after an English sapper who had helped the Russians conquer the city in 1552. Following Butler Street, I arrived in the center of the city. Multistoried white painted shops sold any good imaginable from the inside of their art noveau influenced walls. A massive glass building that wouldn’t have been out of place in Los Angeles hosted a bank. A neoclassical building decorated with Greek-style pillars stood out as well.

I crossed the street and walked passed the university. There were only a few students I noticed, most were presumably in their apartments or classrooms, shielded from the cold. The buildings, never shabby to begin with, became positively exquisite. This was the wealthy part of Kazan. The effect of the sprinkling of snow, the ordered lines of lights, and the exquisite architecture on Castle Street was delightful. The buildings hosted a post office, museums, delicatessens, bookstores, and other government buildings. At the end of the street, I could make out the white walls of Kazan Castle.

As the Mongol successor states declined in the 14th and 15th centuries, news realms rose to fill the power vacuum. On the Oka River, a tributary of the Volga River, Moscow used her privileges as a Mongol tax collector to gain territory and wealth. In the ruins of Volga Bulgaria, Turkic tribes called the Tatars seized power and made themselves the masters of the middle Volga. They reigned over Udmurts, Maris, Bashkirs, Mordvins, and Komi. It is from the mixed descendants of these subject peoples and the Tatars that modern Volga Tatars were formed.

In a series of wars that lasted until 1552, the Tatars of Kazan and the Russians of Moscow fought each other for dominion over the middle Volga. They competed for the allegiance of the Uralic and Turkic peoples. Many fought on both sides, as did foreign mercenaries. Ivan the Terrible finally ended the conflict when he conquered Kazan. The many Russian slaves held by the Tatars were freed, and many Tatars were slain. The Tatar castle on the site of the modern castle was devastated.

On the site of the castle, the Russians first built a church to host the new Christian rulers of the city. It took decades to restore the walls of the castle, but by the early 17th century the castle was considerably larger and better fortified than it had been before. After completion, an English visitor Giles Fletcher reported that the castle was viewed as impregnable.

I could certainly see why as I walked through the castle gatehouse. The walls were perhaps a dozen meters thick, enough to have been a fortification (albeit a weak one) even in the modern age. Similar walls elsewhere in Russia had seen fierce fighting in the civil war of 1917-1923. Inside were the beautiful results of decades long archaeological and restorative work. There was a mosque, several museums, a church, and an Islamic tower.

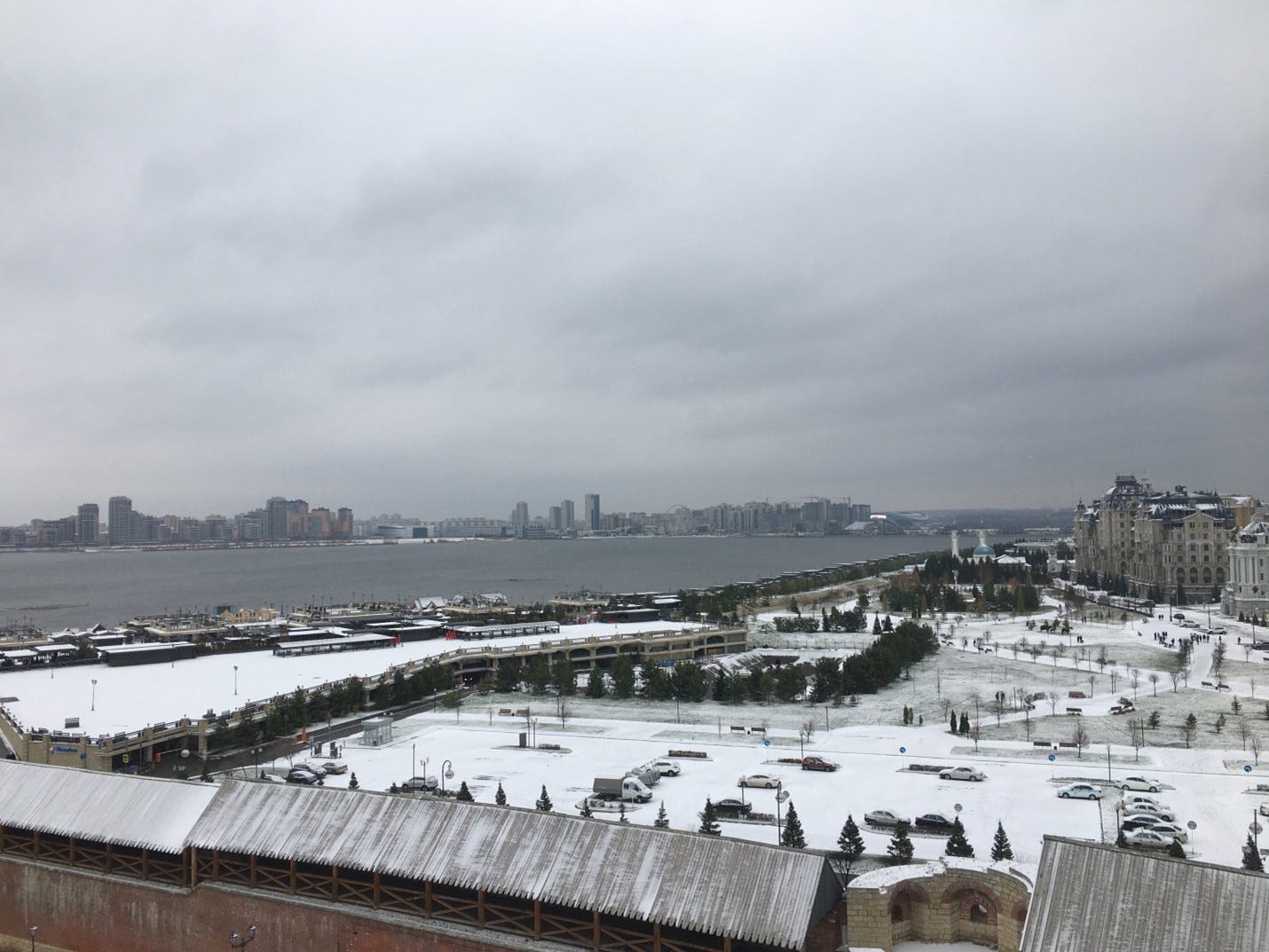

From the walls, I could see the Kazanka River flow into the mighty Volga to the north. The Kama River is just 60 km to the south. To the east, the beautiful Ministry of Agriculture building stands overshadowing a park – covered in snow when I saw it. Fresh air blew in with more snow flurries. I could understand why men loved this land. It was a cold land, and hard, but beautiful.

Inspiring. The Farmers Palace which is so spectacular dates only from 2010, according to Yandex.

I love the style of writing in this text! Switching between your visit and the general history of the region makes this a unique reading experience. I do not know how much of an expert you are on Northern Eurasian history, but one subject I would like you to write more about is the Tatars. Not just Volga Tatars, but a narrative following the identity of "Tatar-ness" and the word Tatar from Siberia to Azerbaijan would be a fun read. Props for this post again.