Along the Chari River in southern Chad, there are two villages named Gori and Damtar. They are 10 kilometers from each other, and are on opposite sides of the river. To an ignorant outsider, the people of these two villages appear to be the same as their neighbors.

The Laal people who live in those villages speak their own language, which has no relation to any other language in the world. The languages of their neighbors are parts of considerably more widespread language families. As Laal people move away from their small towns into larger settlements, they are adopting these languages and being absorbed into the urban populations.

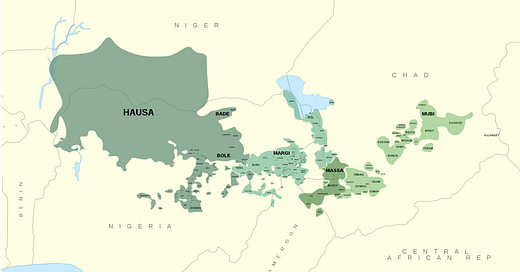

The language of the Laal was just a hint at their unique origin story, a story that goes back to the Neolithic Balkans and involves the far more numerous Hausa people of Chad, Niger, and northern Nigeria. The Hausa language is part of the Chadic language family, shown below.

The Chadic languages, other than Hausa, are mostly spoken in a mountainous band to the south of the Sahel. The Sahel is a semi-arid region to the south of the Sahara Desert that is largely comprised of savannas and grasslands. It’s flat topography has enabled pastoral nomads such as the Fulani to conquer their less militaristic rivals, pushing them to the margins. In that way, the Sahel is an African equivalent to the Eurasian steppe - the land where the horseman, not the infantryman, reigned supreme for millennia. The mountains to the south of the Sahel, both in Chad and in Sudan, hold the remnants of peoples who once ruled the Sahel. Like the peoples of the Caucasus to the south of the Eurasian steppe, they can give us an insight into the past.

All men carry a Y chromosome. Unlike autosomal DNA, which is recombined each generation, the DNA on the Y chromosome is usually passed down from father to son without alteration. However, on occasion the DNA in the Y chromosome is not copied properly, resulting in the son’s Y chromosome differing slightly from that of his father. That is, the Y chromosome carries a new mutation. Scientists, after sequencing the DNA of the Y chromosome, can look at the mutations it carries to classify it in relation to the Y chromosomes of other men. Y chromosomes which share a set of mutations, thus demonstrating a shared line of descent are classified as a haplogroup.

Many men among both the Laal, the Hausa, and other Chadic speaking peoples carry the Y chromosomal haplogroup R1b-V88. It puzzled scientists for a number of years as R1b lineages are most common in Europe, and there was no obvious connection between Europe and sub-Saharan Africa. The puzzlement increased with the discovery of bodies with specifically R1b-V88 lineages in 8th millennium BC Ukraine and 9th or 10th millennium BC Serbia. In the last 10,000 years, the R1b-V88 lineage has largely died out in Europe outside of Sardinia, being replaced by other lineages such as I, R1a, and R1b lineages without the V88 mutation. The R1b-V88 lineage most common within Africa shows a “star shaped phylogeny” that dates to the early 4th millennium BC - that is, the men carrying it at the time were the direct forefathers of many, likely as the result of violent conquests and polygyny. While entire story of Hausa and Laal origins will likely never be known, we do know enough about prehistory to see at least the outlines of the journey of their forefathers.

The world was very different in 7000 BC, not just in technology and human population, but also in geography and ecology. Britain was connected to Europe by a land bridge across the North Sea. The Sahara Desert was mostly a savanna, inhabited by fishermen, foragers, and hunters. The Nile had a third tributary river that flowed from west in what is now eastern Chad to the east in the Dongola Bend.

In Europe, farmers from Anatolia (what is now the Asian part of Turkey) were just beginning to settle Greece and the Balkans. Various hunter-gatherer tribes, some quite distinctive, reigned across the rest of the Europe. In Africa, the northwest was inhabited by a population with affinities to both contemporary Levantines and certain unsampled and non-extant populations in the Sahara - the Iberomaurusians. The Khoe, famous for the clicks in their languages, had not arrived in South Africa. The highlands of Ethiopia were the hunting grounds of a race of short men (though still tall enough to not be dwarves). What we think of as the black race, if it existed at the time, had yet to cross the Mambilla Escarpment in what is now Cameroon and Nigeria east and south.

Beyond the Mambilla Escarpment there were a multitude of races, differing from each to varying degrees, with some quite distinctive. Humanity’s cousin species such as the Denisovans and Neanderthals were long extinct in Eurasia and Melanesia, but it is possible that some had endured past the end of the Ice Age in parts of Africa. Even today, in the highlands of Cameroon, some men still bear lineages that diverged from that of all other men over 200,000 years ago - perhaps a legacy of one of those cousins.

Man’s differentiation in the long ages of the hunter-gatherers was driven in large part by ecology. A tribe who knew how to fish well in a particular environment could find it difficult to hunt game. Tribes who lived in the jungle struggled to survive on the wildlife they came across on the savanna. Savanna tribes faltered in the jungle, not knowing which plants they could consume and exploit. Lacking metal, men found it difficult to change their ecologies, though some did so with fire. Thus men grew further apart, in their lifestyle and in their biology. Evolution was taking us on separate paths, as it had a number of times in the history of our species. It was only on rare occasion one group of men gained some advantage by evolution or technology that enabled him to conquer new ecologies and regions, leveling differences that had once stood with the swing of a club or the stab of a spear.

The advent of farming was one such leveling. The farmers from Anatolia, known as the “Early European Farmers” or EEFs, gradually settled most of Europe in the 6th millennium BC. Able to grow more food from land than their predecessors could gather or hunt, their population grew rapidly. The EEFs, starting at the Danube in 6200 BC, reached Portugal by 5500 BC.

The farmers did not carry Y haplogroup R1b-V88, or R1b at all, at least initially. That was instead carried by the surviving hunter-gathers who skulked in the forests and on the coasts in the lands where the EEFs dared not tread. After all, not all land is suitable for farming.

There was nonetheless some mixing between the farmers and the hunter-gatherers. In the Balkans, some hunter-gatherers were integrated into farmer villages. In Iberia, there was violent conflict between the two races during the colonization of the peninsula. The first known EEF man with the R1b-V88 Y haplogroup was found at an Iberian massacre site from around 5300 BC. His line had likely been founded by a hunter-gatherer in the Balkans who had joined with the farmers early on in their westwards expansion. Another EEF man in late 6th millennium BC northeastern Iberia carried that lineage as well.

In the mid-5th millennium BC, around 4400 BC, there was a great upheaval in Europe - the “Hunter-Gatherer Resurgence”. What caused it is a matter of dispute, but the EEFs were conquered almost everywhere by their surviving hunter-gatherer neighbors. Iberia was no exception. While the hunter-gatherers were absorbed into the larger EEF settled population (increasing the hunter-gatherer ancestry in Iberian farmers to about a quarter of their ancestry), about 80% of the male lineages of the succeeding Middle Neolithic and Copper Age Iberians were from the hunter-gatherers, not the EEFs.

Centuries before that upheaval, some farmers in Iberia had already crossed the narrow straits of Gibraltar into Morocco. They brought their distinctive cardial style of pottery with them, as well as their agricultural lifestyle. Wheat and fava beans were found with cardial pottery in the early neolithic caves of El-Khil (on the Moroccan coast directly across the Straits of Gibraltar), and were dated to the late 6th millennium BC.

Nonetheless, at least some of the influence was at least purely cultural adoption and did not involve population mixing or replacement. Finds in the Cave of Ifri n’Amr o’Moussa date to the end of the 6th millennium BC and include the cardial pottery typically made by the Iberian EEFs of the time. However, the DNA of the human remains shows that they are almost the pure descendants of the Iberomaurusians who had so long reigned in northwestern Africa. The extent of racial heterogeneity within neolithic northwest Africa remains unknown (with it being quite likely that it remained a deeply heterogenous region deep into recorded history). Regardless, it is certain that there was a substantial migration from Iberia prior to rather than after the Hunter-Gatherer Resurgence in Europe in 4400 BC.

The Iberian hunter-gatherers, rather than carrying Y-chromosomal haplogroup R1b as some of the Balkans hunter-gatherers did, mostly carried Y-chromosomal haplogroup I instead. Their assimilation into the masses of their new EEF subjects led the succeeding generations of EEFs in Iberia to carry not just haplogroup I (rather than R1b-V88), but also several extra percentage points of hunter-gatherer ancestry on top of the hunter-gatherer ancestry that the EEFs already had.

The cave of Kehf el Baroud, about 50 km east of Casablanca, contains a woman who died between the 38th and 37th centuries BC. Her ancestry is approximately half EEF, half Iberomaurusian, with her ancestry in the female line being EEF. Her EEF ancestry, when modeled, is specifically from early neolithic Iberia - the EEF settlers of Iberia before the Hunter-Gatherer Resurgence of 4400 BC. Her ancestry as well as considerable amount of EEF ancestry in classical and contemporary northwest African populations thus proves that there was substantial EEF settlement in northwest Africa before 4400 BC.

The full story of the EEF settlement of northwest Africa remains foggy. Much more archaeological and genetic work is needed in order for us to grasp its timing and full extent. However, it clearly had a great impact on the region in spite of the persistence of hunter-gatherer groups likely descended from the Iberomaurusians into the 4th millennium BC. DNA samples from people buried in Carthaginian settlements in Tunisia and Sardinia typically carried a great deal of EEF ancestry, most of it closely related to the woman at Kefh el Baroud rather than to other Mediterranean populations. Contemporary northwest African peoples average around 40% EEF ancestry, demonstrating substantial population continuity for at least the last 5,800 years. Indeed, EEF patrilines ( such as Y haplogroup T-M70, found in Central European EEF populations) survive in modern Tunisia, most notably in Oueslatia. The originally Balkan hunter-gatherer lineage R1b-V88, the signal most relevant to us, is also found in modern Tunisians at a low frequency.

The passage of peoples carrying EEF ancestry, including the R1b-V88 patriline, is even foggier in the Sahara than it is in northwest Africa. The racial diversity displayed in the DNA samples from Carthaginian sites was presumably less than that of the Sahara, as divergent groups exploited the often unique ecological niches in the Sahara with little out-marriage. However, the diversification of populations in the Sahara was likely not as extreme as it was to the south in the rainforests of the Congo River basin, the deserts of southern Africa, and the highlands of Ethiopia. The Younger Dryas (10,700-9,500 BC) and the 8.2-kiloyear event (6,500-6,200 BC) both led to colder and dryer conditions in the Sahara, killing off populations that failed to secure the limited number of reliable water sources and thus encouraging racial homogenization (possibly including through synthesis).

Between those drying events, and afterwards from 6,200 BC to 2,200 BC, surviving populations within the Green Sahara as well as groups on the periphery recolonized newly exploitable lands. At least one of these groups included the male-line ancestors of the Hausa and the Laal.

The Hausa language is part of the Chadic language family, whose dispersal is shown below. While today it is spoke to the south and west of the large and flat Sahel region, there is a fair amount of evidence that those languages were originally spoke far to the east, in the part of the Sahel in what is now Sudan. The Omotic and Cushitic languages of Ethiopia and Sudan share cognates for a number of animals with Chadic languages - most notably in cattle-related vocabulary.

Cows were domesticated as early as 5000 BC in northern Africa. One of the cultures that adopted use of domesticated cattle was the Tenerean Culture. The Tenereans inhabited a range in what is now northern Niger and southern Libya, prior to that region’s desertification. Tenereans seem to have practiced agriculture in at least some parts of their lands, for they made sickles and other tools likely used for agriculture. They also took advantage of sorghum and signalgrass that grew wild on the savanna, as well as fishing in then extant Saharan lakes. It is at one of those dry lakes, Gobero Paleolake, that we have remains of the Tenereans.

While no DNA has been successfully analyzed from the remains, Tenerean skeletal morphology has been studied. They were shorter than their Kiffian predecessors, and their skulls bear no resemblance to that of no known contemporary or previous northwestern African groups. There is some rock art which suggests the presence of a light skinned people in the Sahara in the time of the Tenereans. Artistic representation is of course a weak kind of evidence, but if the Tenereans were partly EEF in origin, some would have inherited the fair skin of their ancestors much as the woman at Kehf al Boroud did.

The Tenereans lacked horses, which at the time were only domesticated in parts of the Eurasian steppe. They herded cattle on foot - a considerably more dangerous and difficult lifestyle than that of later cowboys. Nonetheless, it was a robust way of life. In defeat they could move their livelihoods with them, and in drought they could find new pastures. A farmer by contrast, would usually find death in either defeat and drought. He could not move his fields or his produce. He and his society were tied to his land, sharing its fate. The society of the farmer was thus fragile, the society of the herdsman robust. The farmers could rise higher in times of plenty, but they fell further in times of hardship. Those times, the hard times, were the great opportunity for the herdsman.

It is possible, though unlikely that the Tenereans maintained a distant or indirect contact with Europe. While the EEFs had begun megalithic construction earlier, a new wave of megalith building began after the Hunter-Gatherer Resurgence of 4400 BC. The Tenereans or a nearby population (perhaps exploiting a different ecological niche that enabled it to remain a separate people) simultaneously began construction of megaliths from 4400 to 4100 BC. That, in conjunction with a growing body of genetic evidence of migration from north Africa to Mediterranean Europe during or before the Bronze Age, may indicate contacts between the Sahara and the Mediterranean.

The nomadic Toubou people of the modern Sahara inhabit much of the former range of the Tenereans. Interestingly, the Toubou are about 20-30% Eurasian rather than African in ancestry. A DNA study confirmed that the EEFs (Sardinians are used as a proxy for EEFs in the paper) contributed most of the Eurasian ancestry in the Toubou. While the population history of the Toubou is more complicated and involves subsequent mixing with Eurasian and African populations as well as the adoption of a Nilo-Saharan language, they may be the closest living relatives of the Tenereans.

While there is archaeological evidence suggesting that the Tenereans migrated south out of the drying Sahara into the Sahel around 2200 BC, linguistic evidence suggests that the Chadics originated from the east of the Sahel, rather than the north. The Cushitic languages of the Horn of Africa share a number of cognates with the Chadic languages relating to domesticated animals - in particular goats, cattle, and sheep.

Dating the contact between Chadic and Cushitic is tricky. We have some pieces of evidence that can help us narrow it down:

The Pastoral Neolithic people were in northern Sudan, near the Yellow Nile, by 2000 BC, and were closely related to contemporaries in Kenya

The different words for donkeys, which were domesticated over the course of the 3rd millennium BC, show that contact between Chadic and Cushitic had largely ended by 2000 BC.

the Ethiopian Highlands were not inhabited by either the Cushites or Chadics in 2500 BC

The Leiterband culture of the Yellow Nile (now the dry Wadi Howar in northwest Sudan) and the Ennedi Highlands of eastern Chad fits as the likely location of the contact between the Chadics and Cushites. Leiterband refers to a style of pottery that appeared in conjunction with cattle pastoralism in the Yellow Nile around 4000 BC, and was made until the global climatic crisis of 2200 BC dried up what was left of the Green Sahara.

While there has been no DNA extracted from either Tenereans or Leiterbanders, similarities in their pastoral lifestyles and cattle burials suggest that they bore some relation. The Leiterbanders, like the Tenereans, burned (likely sacrificed) cattle, then buried them. Long distance migration of cattle herding nomads is not unknown even today, although it was also not uncommon in history for foragers and farmers to adopt pastoralism.

Differences in pottery between Leiterbanders and Tenereans suggests that they were alien to each other. Pots are often the best material record of a prehistoric people as they, even shattered, preserve for millennia while organic matter rots away and luxuries are plundered. The nature of their manufacture, the style of their decoration, and the limited ethnic nature of their use can be remarkably conservative across centuries. That enables archaeologists to, with some errors, see the spread of a people across time and space.

While Tenerean pottery shared zigzag motifs with some types of Leiterband pottery, Leiterband pottery has more in common with that of preceding cultures. Were we bereft of genetic evidence, that would suggest that Tenerean influence may have been nonexistent, and any cultural similarities between the Tenereans and Leiterbanders were merely coincidence or cultural convergence.

While it is possible that cattle herding was spread directly up the Nile from Egypt to Sudan by a group not carrying the R1b-V88 lineage, it is unlikely. The R1b-V88 lineage is present today in the Middle East in low frequencies, but almost certainly arrived there via Africa rather than from Europe. The Levant (modern Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria) shows no European-associated (hunter-gatherer or steppe) ancestry until the end of the Bronze Age - more than two thousand years after cattle spread to the Yellow Nile. By contrast, Eurasian (in this case Iberian farmer) autosomal ancestry is detectable even in the modern Laal.

What I believe happened in the early 4th millennium BC was groups of Tenerean men, speaking a language deeply ancestral to the Chadic languages, violently imposed themselves as rulers over some of the peoples of the Nile - including the ancestors of the Egyptians (several percentage points of modern Egyptians carry the R1b-V88 lineage) - in a manner comparable to that of the Mongols establishing themselves as rulers of Iran or the Germans over Rome. The branch of Tenereans that invaded the Yellow Nile region in modern Sudan spread its lifestyle of cattle herding along the river, forming a synthesis with their predecessors that produced the Leiterband culture. The early Leiterbanders practiced widespread polygyny, ensuring that even though their blood was diluted, their Y chromosomes spread to become the dominant line in the Yellow Nile population. Remaining in close contact with the proto-Cushites directly to the east and north of them during the 4th millennium BC, the Chadic speaking Leiterbanders were split from the Cushites during the catastrophe of the 23rd century BC.

With the end of the last parts of the Green Sahara in 2200 BC, the Leiterbanders themselves fragmented, scattering westwards across the Sahel and adopting new material cultures even as they kept their pastoral lifestyle. Their language unity fragmented, becoming as internally diverse as Indo-European. Some groups of Chadics raided into the jungles of Central Africa, eventually intermarrying with and becoming absorbed into the peoples from there, forming the Laal (modern Laal are 1.25-4% Eurasian in ancestry). They arrived in Lake Chad no later than 1000 BC, bringing cattle and the R1b-V88 lineage with them.

The last 3000 years proved unkind to the Chadics. Waves of new pastoral peoples rode across the Sahel, driving the Chadics out of their pasturelands and into mountain redoubts. Only the Hausa, whose adoption of agriculture enabled their population to grow far beyond that of pastoralists (farming can generate 10-20x as many calories per acre as pastoralism) were able to remain a major force.

Thus is the story of a Balkans man and his descendants. Balkans hunter-gatherers who were adopted by or who took over a tribe of Anatolian farmers. Settlers from Iberia who adapted to the Sahara. Saharan cow herders who raided the lands of a now dead river in Sudan. Desperate refugees fleeing the desertification of their old home to the mysterious lands of the south. A proud nomad people ruling the savanna, reduced to farmers, hiding in mountains, or fishermen marrying the peoples of the jungle and adopting a language unlike any other.

I'm sharing this one with readers today over at my Substack.

Really enjoyed, will be paying subscriber if you can put out content at least monthly!