The Indo-European languages are spoken across most of Europe, Iran, and the northern two-thirds of the Indian subcontinent. Because of the huge number of speakers of Indo-European languages, there has been a great deal of interest in the origin of the language family. One early Indo-European theorist, the 18th century British judge William Jones, believed that it had originated in Iran. 19th century German archaeologist Gustav Kossinna believed that the original speakers of the Indo-European languages had originated in northern Germany and Denmark. Others of varying degrees of competence and knowledge followed them, arguing for the original home of the Indo-Europeans – the urheimat – to be in India, the Ural Mountains, the Baltic, or Anatolia.

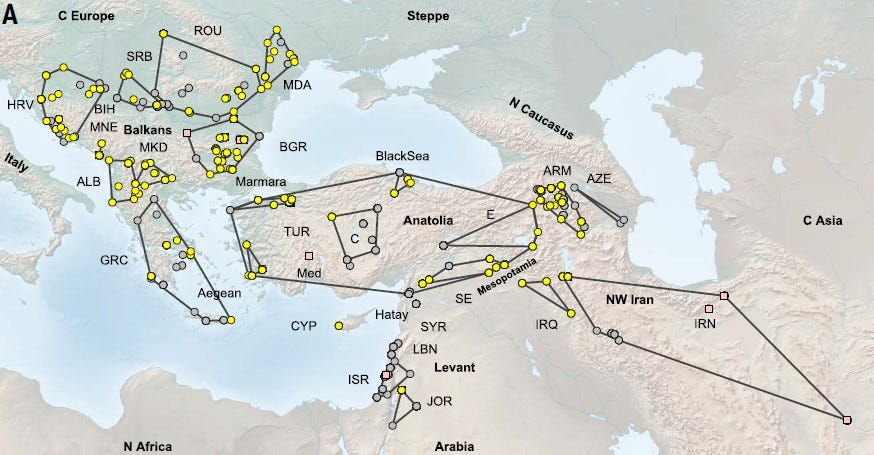

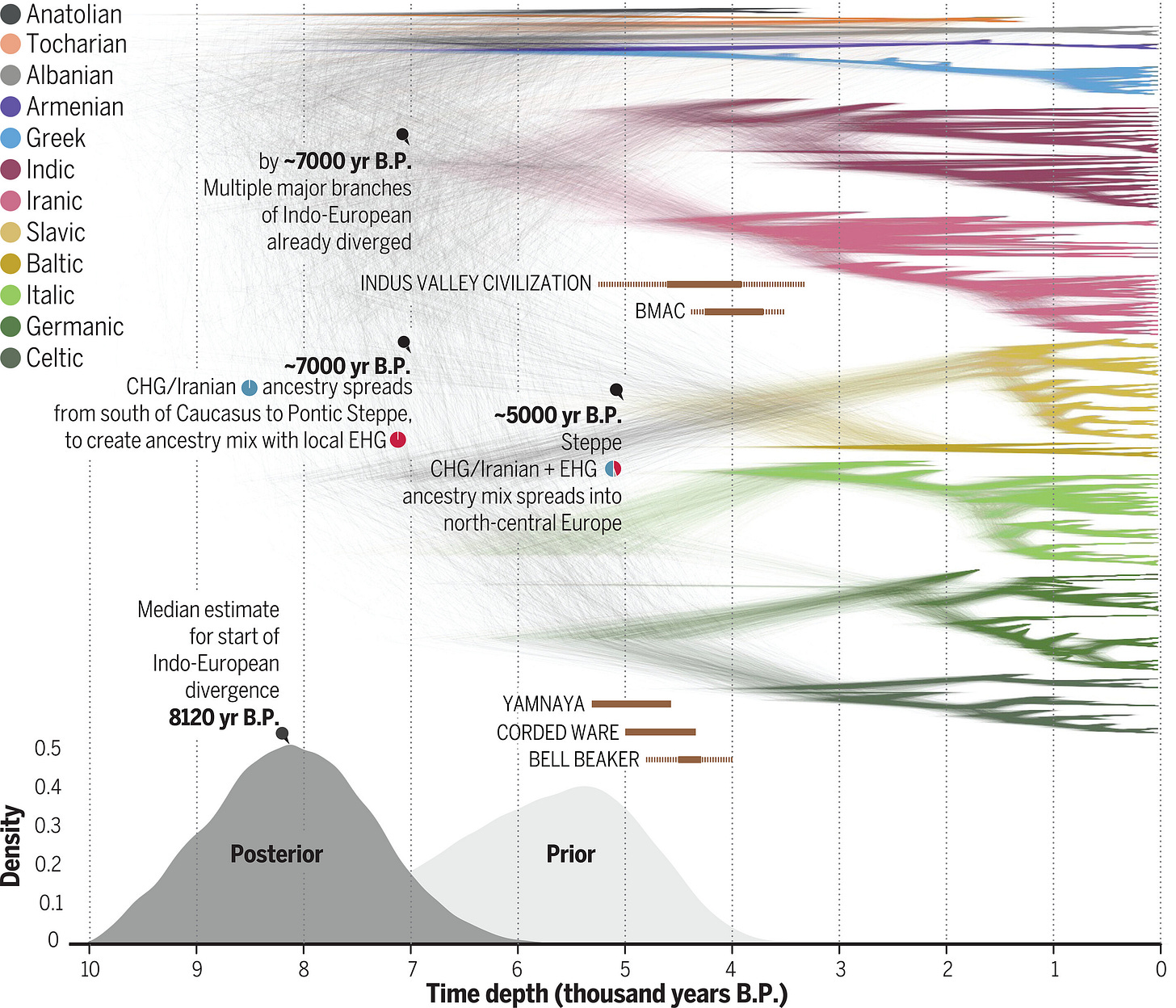

Advances in genetics, linguistics, and archaeology have eliminated all but two theories of the Indo-European urheimat from consideration. The first theory is Steppe Theory – that the speakers of proto-Indo-European – the last stage of the language prior to its fragmentation into multiple branches – lived on the Pontic Steppe in what is now eastern Ukraine and southern Russia some 5,000 to 6,000 years ago. The second theory is Southern Arc Theory – that proto-Indo-European was spoken within the same time frame, but at an unspecified point between the southeastern Balkans and Azerbaijan.

I haven’t made up my mind on which theory I believe, so I will do my best to lay out their cases and problems. It is notable that they differ little in their understanding of the Bronze Age (roughly 3300 BC and after). Their understandings differ instead in the even more temporally distant Copper Age (roughly 4500 to 3300 BC). It is very much possible that too much time has passed for the Indo-European urheimat question to ever be fully resolved.

Most of the Indo-European languages are believed to have fragmented into branches such as Indo-Iranian, Balto-Slavic, Italo-Celtic, Graeco-Armenian, or Germanic during the third millennium BC. However, there were two exceptions. The first is the Tocharian branch, attested in the Tarim Basin of what is now Xinjiang, China in the 1st millennium AD. The second is the Anatolian branch - Hittite, Luwian, and Palaic. The Anatolian languages are attested in the second millennium BC in Anatolia – what is now Asiatic Turkey. Both the Anatolian and Tocharian branches appear to have split from the other Indo-European languages prior to 3000 BC – Anatolian possibly even before 4000 BC.

The Anatolian languages have a number of odd features that set them apart from the other early Indo-European languages. They only have a present and a past tense, while other Indo-European languages have as many as six. They lacked a dual, and they had only an animate and neuter case unlike the other Indo-European languages. Additionally, the Hittite (an Anatolian language) word for wheel is not an Indo-European cognate. Wheels were invented and spread in the second half of the fourth millennium BC. As such, the linguistic and archaeological evidence implies that the Anatolian languages diverged from the main Indo-European languages prior to 3500 BC - centuries before the others.

Theories of Indo-European origins must account for the existence of the Anatolian languages and their early split from the rest of the language family. The Steppe theory and the Southern Arc theory address it in different ways.

The Steppe theory argues that the Anatolian languages are the product of a very early migration out of the steppe. Riding horses from the Indo-European urheimat in what is now eastern Ukraine, the earliest Anatolian speakers were rich in steppe ancestry, split from their cousins, and invaded the eastern Balkans and Hungary in the late 5th millennium BC. There, they created the Suvorovo and related cultures, spreading the ancestors of the Anatolian languages. The Anatolian-speaking Suvorovo people migrated south centuries later, eventually becoming part of the Ezero Culture in late 4th millennium BC Bulgaria and Thrace. Then, during the chaotic period of the 34th century BC (which, characterized by the invention of the sail, also saw the unification of Egypt and the massive Minoan invasion of Greece), they migrated into northwestern Anatolia. There, the Anatolian languages fragmented. The Luwians remained in western Anatolia, while another group of speakers conquered central Anatolia in the early 2nd millennium and formed the Hittite realm. At each step of the path, the original Steppe ancestry was diluted to the point where it was barely detectable in Anatolia.

The Southern Arc theory looks at the Anatolian languages differently. The lack of steppe ancestry in over a hundred ancient DNA samples from the Neolithic to Classical Ages shows that steppe penetrations into Anatolia were too minor and too late to have introduced the Anatolian languages to the region. For instance, Classical Age DNA finds in the city of Gordion are only about 4% Steppe in ancestry - even though the city had been ruled by four separate Indo-European groups. Additionally, the steppe ancestry in the Balkans present in the 3rd millennium BC is entirely from the migrations that occurred earlier that millennium. There is no evidence for any pre-3300 BC steppe-ancestry-rich Indo-European groups in the Balkans surviving to a point where they could have potentially migrated to Anatolia.

The Southern Arc offers another explanation for the Anatolian languages. Instead of originating on the steppe, it argues that the Anatolian languages are the remnants of the Indo-European languages that remained in their urheimat in the Southern Arc - a region from the southern Balkans to Azerbaijan - prior to the language ancestral to all of the other branches of Indo-European spreading north across the Caucasus or Black Sea to the steppe. Increases in Caucasian Hunter-Gatherer and Anatolian and Levantine Farmer ancestry in the steppe population at various points between 4500 and 3300 BC could have been the vector that spread the Indo-European languages from the Caucasus to the steppe peoples. After spreading to the steppe, the non-Anatolian Indo-European languages would have been spread across Europe, Central Asia, Iran, and India.

The Southern Arc theory is a great deal less specific than the Steppe theory, and will need to be fleshed out more. It is possible that the Chaff Faced Ware peoples of the southern Caucasus diffused across the Caucasus in the mid-5th millennium, bringing the Indo-European languages with them. It is also possible that the mighty Maykop people, known to have had cultural contacts with the steppe peoples, could have spread the Indo-European languages to their trading partners as a trade language.

In my opinion, the most likely candidates for introducing the Indo-European languages to the steppe peoples (assuming that the Southern Arc Theory is true) are the mysterious pre-Maykop peoples of the North Caucasus. The pre-Maykop peoples of the North Caucasus interacted with the peoples of the Danube Valley across the Black Sea as well as with the peoples of the steppe in the late 5th millennium BC. Copper from the Carpathians made it to the North Caucasus while boar’s tusk pendants and mace heads from the Caucasus made it to the Danube. However, little is known about them, and it is unlikely that much ever will be known about them. They were apparently destroyed by the Maykop people, and likely have no descendants.

There is a third theory, almost invariably promoted by linguists, which argues for a specifically Anatolian origin of the Indo-European languages. While on the surface it resembles the Southern Arc theory, it’s timing is very different. Rather than a proto-Indo-European language that splits between Anatolian and standard Indo-European in the late 5th millennium BC, it instead places the divergence of the Indo-European languages in the mid-7th millennium BC. It associates the spread of the Indo-European languages with the spread of farming from Anatolia, with the Anatolian Farmers and their European cousins, the Early European Farmers,

The theory has a number of issues. The first is that proto-Indo-European vocabulary (excluding Anatolian) includes vocabulary for wheels and carts that could not have possibly existed prior to 3500 BC at the absolute earliest. It is implausible to suggest that widely diverged groups spread across thousands of miles all independently chose to use the same root words to name wheel-related technology when it arrived it their respective areas.

Additionally, it rejects the close relationship of Balto-Slavic with Indo-Iranian which has been otherwise well attested in archaeology, genetics, and comparative mythology. The theory also times the split of Tocharian from the other Indo-European languages to the 6th millennium BC. While pastoral groups with roots in Iran had made it as far east as Kyrgyzstan in the 6th millennium, the Tarim Basin itself (the place where the Tocharian languages were historically attested) wasn’t influenced by them. I find it implausible that the Tocharian languages were spread west by those herders - particularly given how little Anatolian Farmer ancestry they possessed.

In conclusion, the Indo-European languages likely originated in either the Pontic Steppe (eastern Ukraine and southwestern Russia) or the south Caucasus (Armenia, eastern Turkey, Georgia, and Azerbaijan) at some point in the mid-to-late 5th millennium BC - the Copper Age. The exact location remains to be determined, with ancient DNA results from the Ezero Culture and late 4th millennium BC northwestern Anatolia being particularly relevant to this question. If the Ezero people and northwestern Anatolians from the late 4th millennium BC do not have steppe ancestry, then the Southern Arc theory is likely true as there would be no paths for steppe languages to have spread south of the Black Sea prior to the split of the Anatolian languages from the other Indo-European languages. If they do have a noticeable amount of steppe ancestry, then Steppe theory is likely true as the results would show that a steppe-derived group that had split from its cousins prior to 3500 BC had been able to cross the Bosporus.

Kindly consider a paid subscription to support my writing.

This was utterly fascinating, thank you. Can’t imagine the amount of time and research that must go into writing your pieces.

I hadn’t heard of the Southern Arc theory before, only the Steppe Theory. If I’m not wrong, Razib Khan seems to advocate only for the latter? Though I haven’t read all of his pieces so perhaps I’m misreading him.

Genetic archaeology is such a fascinating new frontier, can’t wait to see what we learn next.

Since *PIE is a linguistic construct the homeland problem should really revolve around its reconstructions. Thus it's always baffled me that any linguist would back the Anatolian theory.

But I think you're wrong (or not completely right) that linguists are its main proponents; in my experience it's archaeologists who like the Anatolian theory best. The reasons are manifold: non-violent expansion (allegedly but implausibly; oh how they love a 'non-violent expansion'), their ignorance of the geography and technology implied by *PIE, similarity to Austronesian expansion (i.e. spread of farming), even the scope it permitted for fitting prehistory into Gould's 'punctuated equilibrium' model. In criticising archaeologists I'm by no means trying to mount a defence of linguists, who are quite as bad in their own ways.

Incidentally, Renfrew largely repudiated the Anatolian theory some years ago, which I thought was very magnanimous of him.

Of the remaining two theories, I'm not sure which is more likely. It's worth bearing in mind that the homeland problem is one thing; the location from where the historically important expansions occurred is quite another. For example, I think there can be little doubt that the Corded Ware/Battle Axe people expanded from the Forest-Steppe zone and not the Caucasus--and we know well how consequential *they* were for European and world history. But then there is the problem of the Armenians, Greeks etc. (see Robert Drews, who favours a much later expansion than the Steppe hypothesis suggests, with--I think--the Caucasus as the urheimat).

There is linguistic evidence of deep structural similarities between Indo-European and Kartvelian languages, but it's also there for Indo-European and Uralic (mainly in the form of tell-tale loanwords, as I understand it). Anyway I will stop now because I'm a dilettante and might get shot down if I continue.

Gud article!