“Canadians have relatively few binding national myths, but one of the most pervasive and enduring is the conviction that the country is doomed” – Andrew Potter

Looking from the year 2025, Canada appears to be a fluke of history. Her prime minister declared her to be a post-national state. Most of her provinces trade more with the United States than they do with the rest of Canada. The vast majority of her population lives within one hundred miles of the USA border, stretched out horizontally across cold regions united only by rail and road. The most natural geographical and hydrological center for Canada, the Saint Lawrence River Basin, is divided politically and linguistically into English Ontario and French Quebec. The utility of the Saint Lawrence River itself in allowing for shipping from the Great Lakes to the World Ocean was superseded two hundred years ago by the Erie Canal. Unnatural in geography, divided by language, opposing a concept of national pride, and bereft of a purpose; the conviction of doom is understandable. Canada exists purely from historical inertia, and could be swept away with ease should her mighty southern neighbor decide on a whim that she has outlived her usefulness.

In 1770, King George III reigned over twenty-four territories in the Americas. The Bahamas, the Windward Islands, the Leeward Islands, Jamaica, Nova Scotia, Newfoundland, Prince Edward Island (then called Saint John’s Island), West Florida, East Florida, Quebec, and Rupert’s Land were counted among his possessions with the famous thirteen colonies. At the time, there were few reasons to foresee the twenty-four colonies divided into two blocs. The divisions between the thirteen soon-to-be rebellious and the eleven loyal colonies were less significant than the internal divisions within the two blocs.

The four Caribbean colonies were based, like those of the Southern colonies, upon chattel slaves harvesting cash crops for export across the Atlantic. Rupert’s Land, occupying most of what are today’s prairie provinces of Alberta, Manitoba, and Saskatchewan; was based upon fur collection and run by company. Nova Scotia was largely populated by New Englanders who had settled on lands seized from the French Acadians in the 1760s, and shared the religion and lifestyle of her sister colonies. Quebec’s minority English-speaking population was similarly derived from New England and as a result profoundly alienated from the French-speaking Catholic majority.

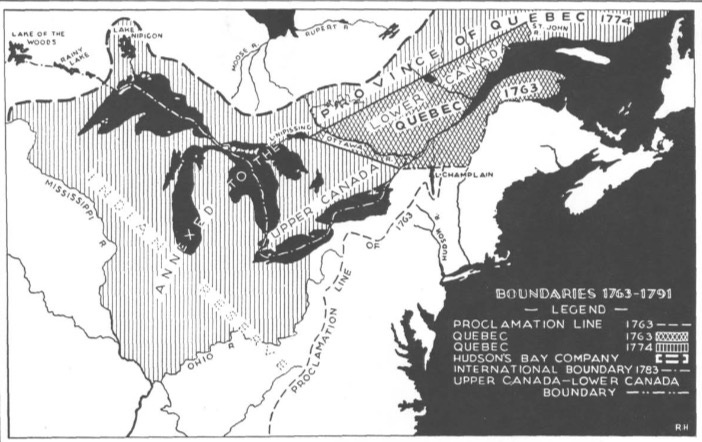

There was little reason at the time to imagine that Quebec, Nova Scotia, Rupert’s Land and Prince Edward Island would ever form a separate, predominately English-speaking nation. Indeed, the fear of British administrators then and Canadian officials even now is that the French-speaking population of their four northernmost colonies, then a majority, would seek to determine their own destiny. In 1774, even more eager to forestall that possibility than the Liberal Party in 1995, the British Parliament passed the Quebec Act. By expanding the territory of Quebec and removing certain legal disabilities for Catholics, it was the first of many political concessions that British and the subsequent Canadian administrations would grant in order to conciliate the French-speaking population. It is perhaps these serious political concessions, granted across three centuries at considerable distaste to the core population, that first gave Canadians their generation-spanning conviction that their country is doomed.

The Quebec Act was included in the five Intolerable Acts which outraged Patriot opinion in 1774, and led to the formation of the First Continental Congress. Its successor, the Second Continental Congress, became the civil government of the nascent American revolutionary state. While it did not include members from the four colonies of the north, it did embrace the ambition of its name and sought to conquer Quebec in 1775. It sent two armies, one under Benedict Arnold, the other under Richard Montgomery, north to fulfill its vision.

The French Catholic elites of the province, while hardly enthusiastic about the Loyalist cause, had little sympathy for the republican ideals of the Patriot invaders. The Quebec Act satiated many of their grievances as well as preserving the social structure based around church and manor. Efforts by the Patriots to create a provincial assembly in Montreal and to send local delegates to the Continental Congress fell on deaf ears. Those who had been sympathetic to the creation of an assembly as early as 1767 had already joined the Continental Army, fled, or were in British prisons. Patriot support was limited to the small, New England-derived English-speaking minority as well as tenant farmers eager to gain the political influence that those of their class could attain to the south. All in all, about 4% of men in Quebec fought in the American Revolution. A quarter of them fought for the Patriots, and three-quarters for the Loyalists.

The divide between Patriot and Loyalist causes in North America was primarily ideological and sectarian rather than national or sectional. Those sympathetic to republicanism rallied to the Patriots regardless of their region or background, while those who felt affinity to imperial institutions or whom believed in the “mixed constitution” rallied to the Loyalists. Two Patriot generals, Moses Hazen and James Livingston, came from Quebec’s English-speaking population, as did perhaps half of the four hundred and fifty men in their two units – the First and Second Canadian Regiments. The remainder, heavily drawn from French veterans who had settled in Quebec following the French and Indian War, were described as a dissolute lot, unattached to their native Catholic Church. American republicanism didn’t just appeal to those whom were parts of democratic assemblies, but also those unattached to any institution but whom still aspired to play an active role in shaping the fates of their at best partially-formed communities. At the end of the war, the survivors settled in New York’s Hudson Valley. Had the invasions succeeded, they would have likely been the rulers of the American state of Quebec.

The failed invasions of Quebec were followed in 1776 by a Patriot invasion of Nova Scotia. Local Patriot sympathizers invited a Massachusetts militia force to conquer the colony. It was defeated. Nova Scotia’s Patriot sympathizers fled to Maine and established a settlement there.

The settlement of the Patriot volunteers from Quebec and Nova Scotia in the United States during and following the American Revolution was only part of a larger population exchange – an exchange which added a sectional and eventually national angle into the existing ideological and sectarian divides. About fifty thousand Americans and ten thousand Europeans who fought for or sympathized with the Loyalist cause settled in Quebec and Nova Scotia following the conclusion of the war, septupling the English-speaking population of Canada. Previously only divided by loyalty, the English-speakers of North America were now divided by an international border.

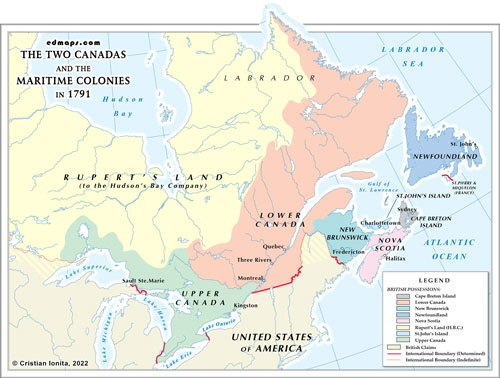

The five northern British territories – Quebec, Rupert’s Land, Saint John’s Island, Newfoundland, and Nova Scotia – were joined by a sixth territory formed from the western parts of Nova Scotia: New Brunswick. About a quarter of the Loyalist refugees, some fourteen thousand people, settled there. Far from Nova Scotia’s capital of Halifax, they were granted their own colony. Another sixteen thousand settled in Nova Scotia proper, and the remaining thirty thousand settled in Quebec. Of the thirty thousand settlers in Quebec, ten thousand settled within the borders of the modern province, while twenty thousand settled southwest, in what was soon to become Upper Canada and would eventually become the province of Ontario.

Those refugees profoundly reshaped Canadian demography. Prior to the Loyalist refugee wave, the five northern territories had a combined population of about one hundred and fourteen thousand. Quebec, with ninety-one thousand people, was by far the most populous of the northern colonies. All but perhaps five thousand of Quebec’s inhabitants spoke French. Newfoundland had an unstable population of six thousand English-speakers, most of whom worked in the fisheries before moving elsewhere. Nova Scotia had a population of fifteen thousand, of whom twelve thousand were English-speakers largely derived from recent, republican-sympathizing New England migration and the remaining three thousand of whom were French-speaking Acadians. Quebec’s demographic dominance gave the entire north a French-flavor, with just short of eighty percent of Canada’s population speaking French natively.

The Loyalist influx to Canada ended the French supermajority. At some point in the late 1780s or the 1790s, additional waves of English-speaking immigrants from the British Isles and the United States (the “Late Loyalists”) would end even the bare majority that the French-speakers held. English-speakers became a majority of the Canadian population – a position that they would hold for the rest of history.

Rather than consolidating Britain’s hold on Canada, the waves of immigration would weaken it. The American Loyalists who cleared out the lands of southwestern Quebec in the 1780s, to become the properly English-speaking Province of Upper Canada in 1791, inadvertently cleared the way for republican-minded Americans. Americans were a fertile, rapidly growing people in the 18th and 19th centuries. By 1815 they were almost two-thirds of Upper Canada’s population. American Loyalists, the original settlers, were outnumbered by that time by recent British immigrants.

In addition to their demographic submersion, the American Loyalists were effectively disenfranchised by the political structure of Upper Canada. As a result of the British reaction against republican and liberal ideals following the American and particularly French revolutions, the British excluded the bulk of the population from governance. In Upper Canada, the government was organized as an oligarchy.

That oligarchy was quite weak. Its authority derived from the colonial bureaucracy in London as well as the status of its members. Trade was regulated abroad, as was the post. The established church, adhered to by only a few, was headed in Quebec and controlled a seventh of the province’s lands. Military and executive authority were held by a military officer sent from the British Isles, rather than a Canadian native. The native officeholders typically followed the instructions of the governor rather than exerting authority on any claimed rights of their own. Even the most democratic political body, the Legislative Assembly, answered only to the wealthiest, and in practice most powerful, part of the population.

Such a political structure may have been viable in a small, densely populated territory. But in a land such as Canada – even on the thin strip of habitable land just north of the United States – the sheer vastness defied attempts to impose authority. In the United States, the solution created by Thomas Jefferson and others was to devolve authority. Localities were allowed to self-organize and send representatives to power centers. Those localities would then accept the decisions made in power centers in return for a role in them. This system enabled the United States to control a vast area with a weak state apparatus, as well as enabling it to mobilize a fraction of the population for war comparable to that of European states with far more sophisticated bureaucracies.

The highly personalistic rather than bureaucratic nature of the oligarchies outside of New Brunswick, the limited size of the political class, and the lack of formal political parties prevented the integration of the masses with the political structure. Whereas European states relied heavily on established churches to organize society in support of the government, only a small fraction of the Canadian population was Anglican. Presbyterianism and Methodism predominated in Upper Canada, while Catholicism predominated in Lower Canada. The result was that most of the Canadian provinces were politically unstable and struggled to mobilize their populations outside of a handful of cities. However, the pro-London governments were able to remain in power despite the draw of the United States precisely because those sympathetic to the United States typically dwelled in towns or rural areas, thus making it difficult for them to shape the politics of the provinces.

New Brunswick was an exception to the general rule of oligarchy in Britain’s Canadian provinces. The American Loyalists who settled New Brunswick in the undeveloped western lands of what had previously been Nova Scotia were disproportionately drawn from the upper and middle classes of society. As a result, when the British attempted to establish a system of landlords and tenants, the American exiles immediately organized themselves to maintain their old social status. They petitioned the governor to instead grant them each a large plot of land which they could individually develop. The result was a province similar socially to the New England and mid-Atlantic colonies which the settlers originated from. Yeoman farmers and individual proprietors (particularly lumberjacks) rose or fell on the successes of their business ventures – not on success in law, war, or religion as in the rest of Canada.

New Brunswick’s society profoundly influenced the local political system. While constitutionally it didn’t begin too different from the other provinces, in practice the Legislative Assembly wielded far greater influence upon the governor.

Had the United States maintained an army of the size that it had in the 1790s then it could have taken advantage of the political instability of the two Canadas with the aid of largely sympathetic populations. The American majority in Upper Canada was broadly but shallowly supportive of the United States even if they were denied a voice in the affairs of state. To their northeast, the Quebecois were embittered by the Anglican bishop’s criticism of the established position of the Catholic Church in Lower Canada. They became infuriated by the government’s arrest of its critics, and may have rebelled if the British hadn’t replaced. However, Jefferson and Madison’s ideological sympathies for a military based around state militias left the United States ill-prepared for any campaigns of conquest.

Jefferson’s belief that the conquest of Canada would prove “a mere matter of marching” was disproven by the repeated American debacles in the War of 1812. American militias invaded from Michigan, New York, and Vermont. The force from Michigan retreated and was captured at Detroit. The force from New York was repelled at Queenston Heights. The force from Vermont simply gave up, seeing their duties as purely defensive rather than offensive – the usual plague of ill-disciplined forces.

The British and the descendants of the American Loyalists had succeeded in repelling those invasions with both cunning and their Indian allies – but notably without a broad mobilization of the population. A bit less than 4% of men in Upper Canada, Lower Canada, Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Newfoundland served in British forces – similar to the share who had fought in the American Revolution – although less when taking into account that the Canadian forces who had fought in the Revolution only fought in one campaign, compared to the three campaigns that Canadian forces participated in during the War of 1812. Notably, the most democratic of the Canadian provinces, New Brunswick, was able to mobilize a far greater share of its manpower for war than the oligarchies of Nova Scotia, Upper Canada, and Lower Canada.

American fortunes in the north improved the following year. More American militiamen under William Henry Harrison recaptured Detroit and proceeded to invade Upper Canada from the west. They were driven back at Frenchtown, but the US Navy won a great naval victory on Lake Erie. The invasion from the east was more successful. American troops under Generals Dearborn and Scott succeeded in crossing the Niagara, sacked what is now Toronto (then York), and then advanced northeast towards Montreal under the treacherous General Wilkinson. Wilkinson was defeated and chased back to New York. Canada was saved. While fighting on the northern front would drag on into 1814, neither side would again penetrate deeply into the other’s territory. The great remaining movements that remained were all far to the south.

Additional waves of immigrants from the British Isles poured into Canada following the War of 1812. Those immigrants, predominantly Scottish and Scotch-Irish non-conforming Protestants rather than English Anglicans, would play an essential role in shoring up Canada’s demography. America was growing rapidly, and the descendants of Americans in Canada were an unreliable demographic. By 1830, Ohio alone had more people than all of the Canadian provinces combined.

Fears of American subversion were quite justified. In addition to the sheer size of the American population, Americans were quickly becoming influential in Upper Canada’s politics and economy. Former Massachusetts congressman Barnabas Bidwell tried and his son succeeded in becoming a member of the Legislative Assembly. American religious dynamism also subverted British authority. Methodist missionaries were feared for their institutional ties to America, especially as members of the established Anglican Church were a small minority of the Canadian population.

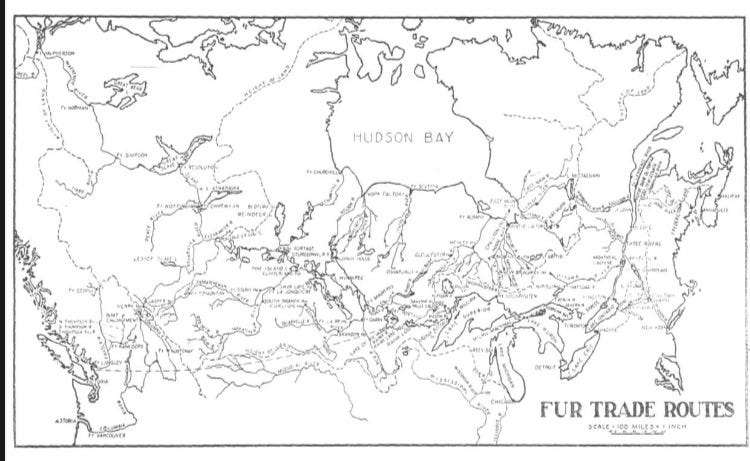

There was also a hydrological and economic angle to their fears. Early European settlement in the Americas was achieved through water rather than by land. As a result, it followed two patterns. The first was the line of settlements along the Atlantic seaboard from Nova Scotia in the north to Saint Augustine in the south, dominated by the British and after 1776 the Americans. The second was along the internal waterways of North America. The second pattern stretched from the outlet of the Mississippi near New Orleans, up the river and its tributaries, across portages to the Great Lakes, through rapids and falls, and finally to the Saint Lawrence River and its outlet near Quebec City.

By the 1820s, the towns along the upper Saint Lawrence River and the northern banks of Lake Ontario were noted by British administrators to have a decidedly American character. Americans were also deeply involved in the push by the fur traders west as far as the Great Slave Lake in what is now central Alberta. In the pre-railroad era, shipping by water was several times cheaper than transportation by land, so the American seizure of most of North America’s waterways was choking Canada’s potential. Nonetheless, prior to 1825 the Saint Lawrence was still the main waterway used to transport goods from the Great Lakes.

That changed with the completion of the Erie Canal. Bypassing Niagara Falls and opening a direct connection between Lake Erie and the Hudson River, it shifted trade away from the Saint Lawrence. Goods which had once been exported to the world’s markets from Montreal were soon being exported from New York City instead, and in far greater volumes. Upper and Lower Canada, formerly great exporters, became mere re-exporters of American goods. Their own native exports became increasingly limited to lumber, and their merchants came increasingly in line with those of the United States.

British patriotism at the time was maintained through social inertia among the upper classes, the reliance of the oligarchies upon London for their local authority, a secret police, state sponsored media, and the poorly enforced tariff system which drove economic dependence on the metropole and prevented closer ties with the United States. The latter was hardly effective, as internal tariffs between the provinces and disputes over customs revenue caused unnecessary strife that would last until Upper and Lower Canada were united in the Province of Canada in 1840. Even a weak tariff system instills a sense of patriotism in the capitalist class. They befriend their counterparts within their bloc rather than outside of it, and give loyalty commensurate with the financial protection that their customs officials provide.

One of the weaknesses of oligarchy over electoral democracy and monarchy is in its inflexibility. An electoral democracy typically votes parties and individuals who fail out of office, and give a chance to new or different party. A true monarchy can replace its administrators on the whim of the monarch to appease the masses for the failings of leadership. An oligarchy, essentially a permanent party government with little to no legitimacy independent of social inertia, takes the full blame for a crisis. It can only be replaced internally through a revolution or reforms introduced to forestall a revolution.

Such is what befell Upper and Lower Canada in 1837-8. The erosion of Canadian economic competitiveness had left Upper and Lower Canada dangerously reliant upon lumber exports. The combination of a bank panic in the United States in 1833 and a decline in lumber prices in 1834 left the Canadian provinces in growing turmoil that culminated in an economic crisis in 1837. Businessmen were ruined, workers were unemployed, and debts were called in.

The existing reform movements radicalized against the provincial oligarchies. Those oligarchies, led by the Tories, radicalized against the reform movements in turn. In Lower Canada, the Patriot Party, dominated by the Quebecois, organized rallies in protest of the government after it rejected their democratization proposals. Inspired by the American Patriots of the 1770s, they embraced anti-clericalism, an Assembly of the Six Counties, and, boycotts of British goods. They formed a paramilitary group, the Sons of Liberty, to fight for their cause. In Upper Canada, a militant reform movement existed but had less popular support and passion. Causes of the intellect go further when attached to a cause of blood, so the French-speaking Quebecois proved more daring and violent than their English-speaking counterparts up the Saint Lawrence River.

The two rebellions both failed. The highly active Methodist Church in Upper Canada preached peace, in line with the teachings of Jesus of Nazareth to “render unto Caesar what is Caesar’s”, while the Catholic Church back the establishment in Lower Canada. Christianity was the most important social glue of the time, and thus clerical support for the colonial governments kept most of the population in line. Similarly, much as in the American Revolution, the urban populations remained loyal to the government. The militant support for reform or revolution was in rural areas, particularly among the tenant farmers of Lower Canada.

The concentration of Tory support in urban areas allowed for the government to assemble forces faster than the rebels. As a result, the Quebecois were crushed bloodily following two defeats on the battlefield, and the English-speaking rebels in Upper Canada were scattered after a skirmish. Their remnants were able to concentrate in a new force reinforced by American volunteers on an island between New York and Upper Canada. From there, they raided into Upper Canada in the name of their newly proclaimed “Republic of Canada”, even more heavily influenced by American republicanism than the initial rebellions. British troops were able to drive the rebels from their holdouts into the United States by the end of 1838, bringing the rebellions to an end.

Victorious in war, the Tories in Upper and Lower Canada were defeated in peace. London sent a Whig rather than a Tory to inspect the two provinces following the rebellion, and he came to the conclusion that the local oligarchies answerable to colonial bureaucrats needed to be replaced with responsible governments – that is governments answerable to their own assemblies. The Tories had killed some of their enemies, and their enemies had won, as understood by the future Prime Minister Justin Trudeau.

The unification of Upper and Lower Canada following the 1837-8 rebellions and the institution of responsible government thus hollowed out the actual forces maintaining British authority. With the old oligarchies superseded, the French nobles sidelined, and the non-established churches ascending in influence; only the draw of tradition and trade kept Canada loyal to Britain. Even then, the latter was soon to dissipate.

Agricultural protectionism was natural in the politically fragmented world of the Middle Ages, and necessary in the early modern period with the improvements in the organization of violence. Men must eat to live, and the disruption of their food supply threatens both the health of men as well as the stability of the state. Thus England used tariffs and exports controls to protect its own farmers. Higher prices in peace ensured that farmers were not impoverished, and guaranteed that the size of their class remained large enough to feed the nation at war.

The long peace that lasted from the conclusion of the Napoleonic Wars to the beginning of the First World War, along with industrialization and improvements in shipping, made agricultural protectionism less necessary. Farmers could earn a higher wage in manufacturing than they could in the fields, and merchants could purchase food abroad in markets that sold it more cheaply than at home. Recognizing that, and desiring to defuse social tensions caused by a poor harvest, the British government gradually reduced agricultural tariffs in the late 1840s.

In Canada, the Tories, still loyal even after their favored political system was slated for replacement, lost faith in the empire with the breakdown of the imperial economic system. The new responsible governments wielded political autonomy, the Quebecois possessed political authority as great as theirs, and the provincial economies were now no longer preferred trading partners in British markets. What then, all wondered, was the point of even being in the empire?

The final blow for many prominent English-speaking Canadians were the electoral victories of the Whigs in Britain’s 1847 election and the passage of the Rebellion Losses bill in 1849. The Rebellion Losses bill awarded a substantial amount of money to those who had property damaged or destroyed during the previous decade’s rebellion. Since most of the destruction was done by the hands of the Tories and suffered by the rebels themselves, the Tories were outraged. The Tories had lost in triumph more thoroughly than they could have ever imagined.

In their outrage, the Tories burned the provincial parliament building in Montreal while rioting in what is now Ottawa. The middle and upper classes, as disgusted by the government’s betrayal as the lower class rioters, wrote sympathetically about developing closer ties with the United States. In Montreal, three hundred and twenty-five leading men signed a manifesto calling for Canada to join the United States. John Abbott, a future Canadian prime minister, was among them.

Had it not been for the increasingly bitter sectional struggles in the United States relating to slavery, Canada may very well have joined the Union between 1849 and 1867. Economic ties with the United States grew rapidly in the 1850s, aided by the Reciprocity Treaty of 1854. The United States surpassed Britain as Canada’s main trading partner by 1860, in line with the predictions and goals of the annexationists. Britain struggled in first the Crimean War and then the Indian War of Independence, so would have been hard pressed to contest a struggle in North America at the same time with a nation which would soon muster millions of men for war. The Reform faction in Canada was institutionally weak even if it had some popular support, and in any case only part of it was truly loyal to Britain. The memories of oligarchies were still fresh in the minds of reformers, and republicanism had appeal. The Tories were divided between annexationists who wanted to create a unified North America with their English-speaking Protestant cousins to the south and those who wanted to unify the British provinces of the north instead.

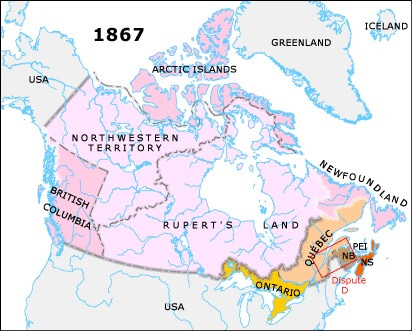

Instead, the United States’ internal disputes led it to miss an opportunity for territorial expansion. The American Civil War left hundreds of thousands dead, destroyed a large part of the country, and horrified Canada. Support for annexation, so widespread in the late 1840s and early 1850s, faded, particularly after the United States’ unilateral abrogation of the Reciprocity Treaty regarding trade in 1866. The Republicans, angry at Canada’s sympathy for the Confederacy and in the grips of a tariff fever, embraced economic protectionism, thus breaking the ties of trade which had created so much sympathy for annexation. The Fenian Raids, launched by Irish nationalists based in Massachusetts against three Canadian provinces in the late 1860s, ended whatever annexationist sentiment was left. Indeed, those raids strengthened the position of the Tories who desired for the provinces to be confederated. In 1867, they succeeded.

The draw of the United States continued to fade as the new Canadian Confederation began to assert itself at home. John MacDonald’s Conservatives enacted their National Policy in the late 1870s. The high tariffs and economic integration with the British Empire revived the old Loyalist identity which had been so prominent earlier in the century. Once again merchants and industrialists were tied to the metropole by their wealth, and those who sought other markets found themselves weaker and poorer – and thus less influential in the heavily patronage based political system.

Similarly, the Confederation was able to consolidate its authority in the Great Plains and in British Columbia. Americans had been involved in the settlement of the Canadian part of the Great Plains since the beginning in the 18th century with Peter Pond, a Connecticut native. Following the conclusion of the American Civil War, American settlers in Montana, many of them Union Army veterans, pressed across the Canadian border in order to sell liquor manufactured goods to the Amerindians. Disorderly and destructive, the Americans became a serious threat to the territorial integrity of Canada as they established a fortified post and imposed their own authority in certain areas. The agency preceding the Royal Canadian Mounted Police was formed in 1873 to establish order, and did so successfully. American border-crossers in the future would do so in a regulated fashion, thanks in part to the efforts of a former Confederate officer who had found a second call to duty in Canada.

The British population of what is now British Columbia was outnumbered nine to one in the 1840s when the United States and Britain agreed on a border in the Pacific Northwest. The ratio shifted even more in favor of the Americans during the gold rushes of the 1850s and 1860s, when the White population of British Columbia became super-majority American at least twice. With its main economic and social connections being to San Francisco rather than any British territory, there was serious discussion in both London and Washington over whether British Columbia should join the United States in the 1860s.

Following the United States’ purchase of Alaska, the British admiralty saw the region as indefensible due to its distance, and the colonial secretary saw it as a burden. Senator Ramsey of Minnesota, seeking to expand the United States, offered to purchase all British territories in North America west of the ninety degree longitude line, essentially everything west of what is now Ontario province. About one percent of the White population, desiring to join the United States, signed a petition requesting that US President Grant annex British Columbia. Ultimately, petitions and offers of purchase were disregarded. While a democratic government in the colony may very well have voted to join the United States, the local government was an oligarchy controlled by a faction that desired to join the Canadian Confederation. So it did in 1871, even though its economy remained dominated by the United States into the 1910s.

American sympathies in the confederation’s population were subtracted by the emigration of substantial numbers of Canadians to the United States. From the 1860s until the first decade of the 20th century more people emigrated from than immigrated to Canada. A full 18% of Canadians emigrated to the United States by 1900, largely following that paths that hydrology and economy set for them. The New York side of the Saint Lawrence River was heavily settled by Canadians in settlement patterns dictated by hydrology and shipping costs. Eastern Michigan, the natural extension of the Ontario Peninsula, was also heavily settled by Canadians. By 1880, a quarter of Detroit’s population was Canadian. Americans and Canadians both settled the Great Plains. By the 1910s, Americans were a fifth of Alberta and a seventh of Saskatchewan’s populations. The Americans in the prairies, along with frontier life, produced a long-lasting political culture close to that of the Great Plains rather than to eastern Canada. Manitoba, formed out of the need for an agreement with the mixed Cree and French population, was only a mere thirtieth American. As a result it, unlike Alberta and Saskatchewan, lacks a regional autonomist party.

American dreams of annexation faded with the immigration of Americanophilic Canadians, but never fully died. Secretary of State Blaine implicitly rejected Canadian sovereignty and worked with a quietly annexationist faction among the then-Americanophilic Liberal Party. Later, Theodore Roosevelt floated the idea for annexation in event of a war with Britain, reasoning that the United States’ dominance on land in North America would more than make up for its deficiencies at sea. President Taft hoped that an expansion of trade with Canada would shift its important businesses to Chicago and New York while turning the country into a virtual American colony. Beauchamp Clark, the Democratic Speaker of the American House, was far more blunt. “I look forward to the time when the American flag will fly over every square foot of British North America up to the North Pole” he declared to broad applause in Congress in 1911. His remarks led to the defeat of the Liberal Party in Canada later that year, as their rivals the Conservatives were seen as reliably anti-American.

While the confederation was more democratic than the provincial oligarchies of the early 19th century, it still wasn’t as democratic as the United States. Financial requirements limited suffrage to less than a tenth of the population in 1867. It wasn’t until the 1885 Franchise Act that suffrage became federally defined. By 1900, most of the male population had the right to vote. The expansion of suffrage forced Canadian political parties to compete with each other for votes, driving the politicization of the population as well as its integration into political structures. Thus Canada was able to mobilize an eighth of its population during the First World War.

The nature of the confederation’s formation proved to hinder its development. The United States was born in the fire of revolution, and was able to write a constitution that was reaffirmed and strengthened in the American Civil War. The US Constitution’s Commerce Clause is taken for granted by Americans, who assume that the federal government will regulate all interstate commerce, and that the states have little to no ability to protect their industries from other states. Canada, formed voluntarily from a mixture of oligarchies and elected assemblies, has considerably stronger provincial governments. Geographical, linguistic, and political barriers as well as naked provincial protectionism have plagued Canada from its foundation. Those barriers impose such a burden upon businesses that most Canadian provinces trade more with the United States than they do the rest of Canada. Indeed, this is the pattern across Canadian history.

The Prairie Provinces of Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Alberta trade more with the Great Plains states than anyone else. British Columbia’s economy is tied closely to that of the American Pacific Northwest, and has been since the 1840s. The Ontario Peninsula began to become extensively integrated into the economies of Michigan and New York in the 1920s, and became even more integrated as a result of trade agreements following the Second World War. The Maritime Provinces were extensions of New England biologically and politically as well as economically at the time of the American Revolution, and maintain their close ties to the present.

It was only after WWI that the English-speakers of Canada gained a noticeable sense of national identity for the first time in its history. Like their counterparts in Australia, the sacrifices of Canadians in war instilled a sense of shared destiny that was able to overcome the views of the previous generations. Bitterness over conscription, as well as the desire of the Quebecois to enjoy their own small part of the world without European interference, inflamed the old divide between Quebec and the rest of Canada. That divide, long covered up by the insularity of Quebecois politics, would surface again with secularization and globalization in the decades to come.

The sense of Canadian national identity was not to last. The United States once again began to economically integrate Canada following the First World War. American businessmen purchased or established factories, particularly in the Ontario Peninsula. By the end of the 1920s, a quarter of manufacturing wages were earned from American companies. The American share of imports and exports exceeded what it had been during the Reciprocity Treaty of 1864-1866. 1.16 million people emigrated from Canada to the United States during the decade, eager to partake in the opportunities offered – almost a tenth of the Canadian population. The result was that in 1940, a tenth of immigrants in the United States had been born in Canada, and the overall population of the United States was 1% Canadian. The share of the US population with Canadian roots amounted to perhaps a third of Canada’s 1940 population. As in the 19th century, English-speaking Canadian emigrants were disproportionately drawn from the educated and the productive classes.

The Second World War and the Cold War expanded upon the growing economic integration with military subjugation. In 1940, Canada and the United States formed the Permanent Joint Board on Defense, coordinating their military and industrial strategies against Germany, and effectively turning Canada’s military into branches of the United States military. The subordinate relationship was expanded in the 1950s with the creation of NORAD’s predecessor. In NORAD, Canadian forces were placed under the control of Americans, and American troops were deployed on Canadian soil.

Economic integration and military subjugation were paralleled by the death of the nascent English-Canadian nationalism. Canada had never had a strong identity. A mere quarter of the English-speaking population held views that could be fairly described as ethnonationalist during the height of those views in the Second World War. About half of the population during the war held views consistent with a civic sense of national belonging. That is, mere possession of Canadian citizenship along with the willful and public adoption of shared culture would make one a Canadian. That willful and public adoption of shared culture in Canada’s case meant an obligation to acculturate to a truncated set of British behavioral norms which had been partly shaped by the nature of emigration to North America. The combination of Britain’s realignment with Europe, the economic and cultural draws of the United States, and the increasing assertiveness of the Quebecois all worked to extinguish any sense of shared culture or identity.

Progressive Conservative Prime Minister John Diefenbaker, 1957 to 1963, saw that Canada’s national identity was fading and worked to strengthen it. From Saskatchewan, a prairie province, rather than the more populous Laurentian provinces of Quebec and Ontario, his ideology was typical of post-war conservatives in the English-speaking world. He combined Prairie Populism, Tory Loyalism, and market liberalism into a synthesis that was effective electorally but ineffective at governance. The old populist ideology was incapable of influencing much less dominating the large-scale bureaucracies and institutions that characterize industrial society. Market liberalism and its emphasis on free trade naturally undermined traditional forms of authority that those like the Tories drew upon for legitimacy and guidance. That was particularly true in Canada’s case due to the vastly larger size of the American market over the British, as well as the desire of the Americans to integrate the Canadian economy but the desire of the British to integrate with the continental European economy.

Diefenbaker’s most important failure, and Canadian nationalism’s failure more generally, were their inabilities to understand that the Quebecois were a truly separate nation. The Quebecois separatists of the 1960s and 1970s were correct in insisting that Canada was not a nation, but a country inhabited by two nations – the English-Canadians and the Quebecois. Rather than realizing this, and seeking either de facto recognition for the English-Canadians through a sectional Canadian bloc excluding Quebec or a de jure recognition of English-Canadians as a constituent nation in Canada, the demoralized English-Canadians decided that they were not a nation at all.

The English-Canadian responses to Quebecois aggrandizement and state bilingualism in the 1960s and 1970s varied. As they lacked confidence in themselves after the fall of the British Empire and were bereft of any non-electoral political structure which could represent them against the rising bilingual elites, the English-Canadians drifted towards policies without much thought.

Some drifted towards multiculturalism, as it offered them rhetorical and moral equality without requiring them to work hard for political representation. If the Quebecois were one of many nations in Canada rather than one of two, then the English-Canadians could cynically use other communities as a shield for their interests. Appeals to universal rights, even if they reach towards the lowest-common cultural denominator, are naturally easier to argue for than a policy which would benefit the majority in a particular fashion. The inevitable accusations of fascism and racism can be sidestepped, and the costs of rhetoric and policies are deferred to future generations.

Others, particularly in the prairie provinces who had been bereft of a regionally oriented party since the decay of the Social Credit Party in the 1960s, drifted towards a form of conservatism heavily influenced by that of the United States’ Republican Party. Forming the Reform Party in 1987 to bypass the chokehold on the political right previously held by the Progressive Conservative Party, they eventually merged with Progressive Conservatives in 2003 and took over the resulting Conservative Party of Canada. Reform publicly advocated for a united Canada, with no special position for Quebec. Its leadership quietly supported Quebec independence, seeing it as a social and economic burden that Canada was better off without. Had the 1995 Quebec sovereignty referendum passed, Reform’s leader Manning planned on toppling the Liberal government in a new election and recognizing Quebec independence.

The consequences of state multiculturalism and bilingualism were difficult for the people in the 1960s and 1970s to imagine. Rhetoric leads to commitment, and commitment in time means the enactment of policies. Policies require bureaucracies, and those bureaucracies, in time, find reasons to expand their reach far beyond the initial intentions of activists and politicians.

Canada’s Charter of Rights and Freedoms serves as the Canadian equivalent of both the American Bill of Rights and the Civil Rights Act. It enshrines both liberties as well as entitlements. The entitlements, much as in the United States, were later found by judges to supersede certain liberties. Indeed, some of the entitlements required a reorganization of society and culture. The Charter, along with the Multiculturalism Act of 1988, obligated companies and civic organizations to actively advance the interests of “racialized” populations. Unlike in the United States, where civil rights law applies to everyone, Canadian law grants special representation and privileges to select groups which are not presently perceived to be part of the deracialized English-Canadian heritage population. The concepts of representation and privilege in the Canadian context are understood similarly as they are in the United States.

Canada’s multiculturalism policies created disciplinary and alignment organs similar in function to party cadres of the Soviet Union while similar in practice to the less suffocating human resources departments in the United States. Western states, Canada included, avoid imposing unpopular indoctrination programs upon the public by devolving that responsibility to most private institutions. Typically that comes in the form of human resources departments, which indoctrinate and discipline their workers to ensure that the institution can’t be punished by state bureaucracies or the courts. The general population is thus aligned with state ideology in a manner devised by the institutions with which they voluntarily interact.

Notably, this decreased state capacity. The older, more democratic organs of the Canadian government worked with voluntary organizations such as the Orange Order or Catholic Church to mobilize hundreds of thousands of people to meet crises such as the world wars as well as smaller matters. The newer organs are far better at indoctrination, but inferior at mass mobilization than the old. Paid community activists and NGOs cannot replicate the old organic organizations upon which mass democracy was based, but they are certainly more loyal. Few will bite the hand that feeds them.

Multiculturalism and bilingualism thus ended the democratic period of Canadian history which lasted from 1885 to 1982. Power was taken by the federal government from the provinces, then devolved to the legal class and bureaucracy. The legal class was set apart from the general population by their credentials and thus class, while an increasing share of bureaucratic positions were required to be held by English-French bilinguals. As bilinguals were less than a fifth of the population, the reservation of 40% or more of positions for them gave power to a narrow stratum of Canadians unrepresentative of both the English-Canadians and Quebecois. Critically, that narrow stratum was largely immune to competition from immigrants, the vast majority of whom choose to learn either English or French alone rather than in combination. While adult citizens can vote for new elected officials in nominal elections, their ability to enact meaningful change is restricted by two factors. The first is that officials bent on change are effectively powerless if they tried to oppose the entrenched bilingual bureaucracy, the legal class and supervisory institutions like the Royal Canadian Mounted Police and the Human Rights Council. The second is that state bilingualism, institutional suffocation of organic public sentiment through multiculturalism, and the need to appeal to the notoriously self-interested Quebecois filter out most politicians who would even wish to oppose the established powers in Canada.

In a way, state bilingualism and multiculturalism have replicated the old colonial oligarchies. Power is derived from a state apparatus rather than the people, while legitimacy is obtained through management of communities, whose actual representatives are chosen by the state. Institutions with moral authority, then the Anglican Church and now human rights agencies, have formal power, as do the security forces due to a lack of political oversight and enmeshment with the media. The elected legislature has power in theory, but in practice can only confirm the decisions made by the real powers.

The limited size of the politically active classes, the disciplinary organs of state multiculturalism, and the nature of parliamentary governance made it easier for oligarchs to capture state institutions. Families like the Westons, the Irvings, the Desmaraises, and the Sutherlands and the companies that they own cultivate close relationships with rising politicians; easily coopting them and preserving their monopolies or protections. For instance, notable Conservative figure Jenni Byrne, a top advisor for former Prime Minister Stephen Harper and current Conservative leader Pierre Poilievre, works closely with the Weston family. The old colonial oligarchies with their powerless legislatures and dominated by the establishment, were resurrected in a modern form.

The multicultural policy adopted by Pierre Trudeau were successful in the short term. Mostly rhetorical in his first period in office, it successfully undercut the separatist movement in Quebec to the point that the first sovereignty referendum in 1980 lost by almost twenty points. The population outside of Quebec was still quite homogenous, so immigration from the Third World added flavor rather than chaos to Canadian society. The reglobalization of the world inspired most, Trudeau himself included. By 1995, it had the added benefit of keeping Quebec in the federation, as the disproportionately English-speaking immigrant neighborhoods voted to remain in Canada.

Trudeau’s protectionist policies, such as the Foreign Investment Review Agency and the National Energy Program, aimed at preserving Canadian sovereignty. That political integration would follow the already extant economic and military integration was a very real fear, so self-sufficiency in energy and state approval of foreign investment were prudent measures. However, they resurrected issues with the prairie provinces that have yet to be fully resolved, and in any case were swept away by the next prime minister.

The Prairie Provinces – Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Alberta – were largely depopulated at the time of confederation in 1867. While Manitoba was an original member of the Confederation, Saskatchewan and Alberta only became provinces in 1905. As a result of their infant political systems, the federal government controlled their resources, inspiring resentment as the provinces grew. It was not until the Natural Resources Transfer Act of 1930 that the three prairie provinces gained control of their resources. The taxation of those resources beginning in 1974 and the National Energy Program in 1980 reignited those resentments. The people of the prairie provinces correctly saw the programs initiated in Ontario with support of the eastern provinces as redistributing their fairly earned wealth. Some prairie politicians like Roy Romanow were embittered to the point that they desired to secede from Canada altogether, forming a Western Federation of Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta, and British Columbia. Had the 1995 Quebec Referendum ended in Quebecois independence, he would have also declared independence.

The 1980s saw a revival of market liberalism across the West. Canada was no exception, and moved to lower her protectionist barriers and seek greater trade with the rest of the world – particularly the United States. The alienation of the prairie provinces was alleviated through the abolishment of the National Energy Policy and privatization of Petro-Canada. A trade agreement with the United States was reached in 1988, and would be superseded by NAFTA in 1993.

The trade agreements with the United States dramatically shifted the economic and social orientations of Canada. Internal trade barriers stifled the development of the Canadian market, driving the most enterprising Canadian businessmen towards the US market. International trade with the United States grew considerably faster than Canada’s interprovincial trade. While interprovincial and international trade had been roughly equal prior to the free trade agreements, by 2000 over 80% of trade was international rather than interprovincial.

Although the Quebecois had voted overwhelmingly to remain in the federation in 1980, they opposed the 1982 constitution and patriation from the United Kingdom. The provincial government outright rejected the constitution when asked to sign it. The matter was taken to the Supreme Court, which ruled that the constitution was nonetheless in effect in Quebec. The constitutional matter festered for years, eventually leading to the Meech Lake Accords in 1987. In the negotiations at Meech Lake, the Quebecois sought recognition as a distinctive society within Canada as well as a greater devolution of powers to the provinces.

The accords fell apart, and thus revitalized the Quebecois separatist movement, which had never accepted the new constitution. Denied formal recognition of their status within Canada, Quebecois leadership decided to seek their destiny outside of her. The Bloc Quebecois was formed as the federal counterpart of the provincial Parti Quebecois in 1991. It won 54 out of Quebec’s 75 seats in the 1993 election, and supported the 1995 Quebec sovereignty referendum. Ultimately, the referendum failed and Quebec remained in the confederation. Quebec’s loyalty was bought with generous subsidies through Canada’s provincial equalization program. English-Canadians, stuck with the Quebecois, tried to form a identity inclusive of the Quebecois, but it failed to take root in the population which government policy had deliberately deracinated.

Canadian society had long been influenced by that of the United States, but the greater economic integration as well as improvements in communications technology drove an even greater cultural convergence. Canadian actors, writers, activists, and other cultural figures continued to move to the United States as part of a two-century long trend of brain drain southwards. Those who were left were invariably of lower quality than the emigrants, leaving genuine Canadian culture increasingly parochial and inferior. Rather than embrace their own increasingly derivative culture, Canadian elites instead aped the fashionably anti-American attitudes embraced by American Democrats. That process was aided by television. The concentration of the Canadian population along the southern border enabled them to receive first radio and then television signals from the United States. While the Canadian government tried to promote Canadian and restrict US content, US media became dominant in time anyways. Within twenty years, even the Canadian right would ape the attitudes of the American Republicans. English-Canadians, united again in trade and culture with Americans, became essentially Americans without citizenship.

By the 2000s, Canadian politics were downstream of and reactive to those of the United States. Bush II’s invasion of Iraq drove a wave of anti-war sentiment even though Canada didn’t participate in the invasion. Canadians became reflexively supportive of their healthcare system despite prior complaints. Commitment to international law and institutions were allowed to supersede domestic interests to the point that Canada accepted partial responsibility for the Rwandan Genocide in 2010.

That trend accelerated in the 2010s and 2020s under Prime Minister Justin Trudeau. While the United States saw a rise in anti-immigration sentiment, Canada invited in 13.7% of her population from 2015 to 2025. Canada enthusiastically embraced the Black Lives Matter movement, with Prime Minister Trudeau kneeling to George Floyd - an unprecedented act as Prime Ministers merely curtsy to the king or queen of Britain. Canada found her own parallel to BLM with the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls inquiry as well as the supposed residential schools genocide. The inquiry found that Canada was actively committing genocide against Amerindian women as late as 2019. Trudeau accepted the findings of the inquiry. He later tacitly supported the burnings of churches which had been blamed for the supposed residential schools genocide.

Canada’s long-delayed doom is visible at long last. The inertia that has preserved the Canadian state has been dampened. Neither Pierre Poilievre nor Mark Carney, the two possible prime ministers, have the will, men, or vision to make a nation out of Canada. The three provincial autonomist parties in Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Quebec all have long-standing issues with Canada’s constitution and federal government. The decay in state legitimacy as the result of its own actions as well economic stagnation have exacerbated the tensions of those three provinces with the federal government. The Quebec issue threatens to flare up in 2026 with a pending provincial victory of the separatist Parti Quebecois – particularly if Poilievre and his Conservatives control the federal government. If Carney wins, the western provinces, particularly Alberta, will start a new constitutional crisis over control of provincial resources. The ill-thought out multiculturalism policy has borne its bitter fruit with large anti-Semitic marches, a proliferation of ethnic self-aggrandizement, and a collapse in Canadian patriotism.

Most ominously, the long friendly United States, alienated by the naked abuse of intelligence sharing and designation of groups supportive of the president as terrorists, openly plots annexation. Perhaps an American, seeking to surpass his Revolutionary ancestors, will follow their path and sweep the old northern order away for all time. After all, why should Americans allow those of our own blood and culture to live under a government hostile to our interests? Is not British Columbia an extension of our Pacific Northwest? Are not the Prairie Provinces - particularly Alberta - part of the Great Plains? Nova Scotia has always been an extension of Massachusetts, and New Brunswick was founded by Americans. Quebec alone of the Canadian provinces is alien to us.

Sources:

British Columbia and the United States by James Shotwell

Canada & the American Revolution by Gustave Lanctot

The Canadians by Ogden Tanner

Crossing the 49th Parallel by Bruno Ramirez

The Empire of the St. Lawrence by Donald Creighton

A History of Alberta by J.G. MacGregor

The Incredible War of 1812 by J. Mackay Hitsman

Lament for a Nation by George Grant

The Loyalists by Christopher Moore

The Morning After by Chantal Hebert and Jean LaPierre

The Other Quiet Revolution by Jose Igartua

Political Unrest in Upper Canada 1815-1836 by Aileen Dunham

The Resettlement of British Columbia by Cole Harris

Rise to Greatness by Conrad Black

With Scarcely a Ripple by Randy Widdis

Selling Illusions by Neil Bisoondath

This Unfriendly Soil by Neil MacKinnon

This makes me realize, as an American, how little I know or understand re Canada’s history, and the dynamics behind it. Interesting, the part about bilingual bureaucrat elites, and the impressive Mr. P’s connections.

I hope Canada makes it

We don't want them. The most right wing Canadian is a socialist. Make the Canadian Provinces states, and the Democrats will have a veto proof majority in the Senate. It would also guarantee the net President would be AOC. No, thanks. We don't want them.