Plague, war, and invasion devastated the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire in the 7th and 8th centuries AD. Even the parts of the empire spared conquest or devastation regressed materially and culturally. Learning was almost extinguished. However, the Empire began to recover in the 9th century. Both the Empire’s treasury and borders expanded, and learning returned. Greatest of the teachers of the 9th century was the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople, Photius I.

Photius I was a polarizing figure in his time, assailed for his political actions while acclaimed for his scholastic achievements. One of those achievements is his Bibliotheca - a collection of his reviews and notes on 279 books. As most of those books are now lost to history, Photius’ summaries and notes are all that we know of them.

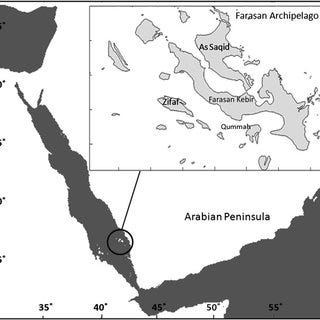

One history that is only known through Photius’ Bibliotheca is that of Nonnosus, a 6th century AD diplomat who journeyed to Arabia, Yemen, and what is now the Tigray region of Ethiopia during the reign of the Emperor Justinian. On his return voyage from the Kingdom of Axum in Ethiopia, Nonnosus saw pygmies in the Farasan Islands.

During his voyage from Pharsan, Nonnosus, on reaching the last of the islands, had a remarkable experience. He there saw certain creatures of human shape and form, very short, black-skinned, their bodies entirely covered with hair. The men were accompanied by women of the same appearance, and by boys still shorter. All were naked, women as well as men, except for a short apron of skin round their loins. There was nothing wild or savage about them. Their speech was human, but their language was unintelligible even to their neighbours, and still more so to Nonnosus and his companions. They live on shell-fish and fish cast up on the shore. According to Nonnosus, they were very timid, and when they saw him and his companions, they shrank from them as we do from monstrous wild beasts.

Such were among the last remnants of the pygmies of the Red Sea coast. While pathetic by the 6th century AD, they had not always been so. Indeed, three thousand years before they had been valued trade goods for the mighty men of Old Kingdom Egypt and known by the powerful for their connection with the supernatural.

The story of Harkhuf, a powerful governor in 23rd century BC Egypt is well known due to the autobiography inscribed on the stone of his tomb. It includes a congratulations from the Pharoah regarding a trade expedition that brought back a deneg from “the lands of the horizon-dwellers”. It also references a previous trade expedition to Punt (now known to be modern Eritrea and eastern Ethiopia) under the 25th or 24th century BC Pharoah Izezi which had also brought back a deneg.

You have said in this dispatch of yours that you have brought all kinds of great and beautiful gifts, which Hathor mistress of Imaau has given to the ka of King Neferkare, may he live forever. You have said in this dispatch of yours that you have brough a deneg of the god’s dances from the land of the horizon-dwellers, like the deneg whom the god’s seal-bearer Wedjededba brought from Punt in the time of King Izezi. You have said to my Person that his like has never been brought by anyone who did Yam previously.

…Come north to the residence at once! Hurry and bring with you this deneg whom you brought from the lands of the horizon-dwellers live, hale, and healthy, for the dances of the god, to gladden the heart, to delight the heart of King Neferkare, may he live forever! When he goes down with you into the ship, get worthy men to be around him on deck, les he fall into the water! When he lies down at night, get worthy men to lie around him in his tent. Inspect ten times at night! My Person desires to see this deneg more than the gifts of the mine-land and of Punt!

When you do arrive at the residence and this deneg is with you live, hale, and healthy, my Person will do great things for you, more than was done for the god’s seal-bearer Werdjededba at the time of King Izezi, in accordance with my Person’s wish to see this deneg.

Deneg was one of the three Ancient Egyptian words for unusually short people, and is possibly related to the contemporary Amharic word denk, which has the same meaning. The other two words, nmw and hw, appear refer to unusually short people who are deformed - dwarfs rather than normally proportioned pygmies. In addition, while deneg is associated in Egyptian texts with southern lands, Punt or the Land of the Horizon Dwellers, nmw is never associated with any locations.

It is not certain that deneg refers to pygmies. All ancient Egyptian burials of very short people found thus far have been of dwarfs, not pygmies. In addition, the determinative of the references to deneg in Harkhuf’s autobiography depicts a dwarf rather than a pygmy, although it could be that the determinative in that case could be used for both dwarfs and pygmies.

Curiously, the archaeological reports associated with Punt, the Gash Group, don’t make any mention of pygmies. Similarly, while Egyptian art depicting the people of Punt, such as of Punt’s Queen Eti in the 15th century BC below, shows at least some cases of steatopygia, it also does not show pygmies.

Around the time of the Egyptian expedition to Punt in Izezi’s reign, there lived a man in the highlands of Ethiopia - to the west of Punt. He was buried in Mota Cave in the Gamo Highlands. His race ranged at least across southwestern Ethiopia, where peoples even today such as the Majang, Bench, Sheko, Aari, & Gumuz largely descend from them. As an adult, he was a mere 154.8 cm to 158.2 cm in height, considerably shorter than malnourished neolithic and classical age farmers, but still noticeably taller than the 145 cm norm for pygmies. Could his relatives have been the deneg? Could their land been “the land of the horizon-dwellers”? It is doubtful - while I couldn’t find statistics for the heights of the peoples of the Omo Valley, the photos I found don’t suggest that they are unusually short. Of course, it is possible that they’ve evolved to be taller in the last 4,500 years - others have certainly evolved to be shorter or taller in that timeframe. Additionally, the peoples of the northern Ethiopian highlands manufactured their stone tools differently from the Late Stone Age methods used by known pygmies.

So where did the deneg come from? They didn’t come directly from Punt, nor were they in the Ethiopian highlands. The current pygmy lands in the Congo and the African Great Lakes were too far south to be the source. It could be that they were the neighbors of the people of Punt in Somalia. The Cushitic peoples (present range shown below) who currently dominate the Horn of Africa were only just beginning to penetrate the region in the 3rd millennium BC. Their ancestors at the time were predominately in the middle Nile in what is now north-central Sudan. The Cushites who did roam around the Horn were just one of several races in the region. Late Stone Age hunter-gatherers and fishermen endured for millennia, sometimes living nearby the Cushites.

Archaeology of the east African coastline is tragically understudied. It appears that the fishermen of the coast were less technologically sophisticated than those of the Rift Valley, as they possessed only a Late Stone Age toolkit called the Wilton Culture. Interestingly, the peoples with that that Late Stone Age toolkit appear to have been remarkably well adapted for coastal life, reaching from as far south as Ballito Bay in South Africa to Eritrea and the island of Dahlak Kebir in the Red Sea as late as the last few thousand years.

One group that may descend in part from those coastal fisherman is the Sandawe of modern Tanzania. The Sandawe speak a click language unrelated to any other in East Africa, and are quite genetically distinctive from all of their neighbors - even the other regional group that speaks a click language - the Hadza. While most of the ancestry of modern Sandawe comes from later pastoralists and farmers - the Cushites in particular - a noticeable part of their ancestry is linked to the very distinctive Ballito Bay population in South Africa 2000 years ago. While the Hadza also have a bit of an affinity to the Ballito Bay people, the Sandawe have an additional affinity to them that accounts for perhaps a tenth of their old pre-pastoral ancestry. That suggests that in addition to tremendous prehistoric diversity in East Africa, that the coastal populations were likely interacting with each other more than interior groups.

The San people of modern Botswana, Namibia, and South Africa are relatively closely related to the Ballito Bay people of 2000 years ago. While the Sandawe are a normal height by human standards, the San are unusually short. San men average about 156 cm in height with standard deviation of 5.5 cm. Could the old coastal and un-pastoral admixed cousins of the Sandawe have been the deneg brought to Egypt via Punt in the 25th century BC? I think it is possible. Pygmy men average around 145 cm in height, so if the pre-pastoral ancestors of the Sandawe were of the same height as their distant San relatives, then several percentage points of their population would be short enough to qualify as pygmies. The men of Punt may have raided into Somalia (where the Somali-speaking relatives of the Sandawe - the Eyle - still live), taken the shortest of the old non-pastoralist Sandawe-like people captive, then sold them to Egyptian merchants as deneg.

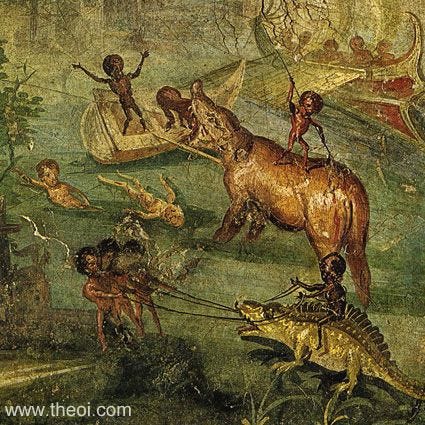

However, such an explanation would not explain why Nonnosus saw pygmies in the Farasan Islands. It is possible that the late stone age groups in the Horn of Africa included yet unfound pygmy populations - a real possibility given the paucity of archaeological work in the region. Regions populated by hunter-gatherers could be highly diverse, with differences in choices of ecologies to exploit allowing for long term coexistence of highly divergent groups. The finds of Wilton tools on Dahlak Kebir show that the coastal populations were capable of sailing the Red Sea. However, it seems more likely that the pygmies of the Farasan Islands were brought there. The jungles that the pygmies thrived in did expand to the east and north during the African humid period at the same time as the Green Sahara, but they did not reach the Red Sea. The pygmies of the Farasan Islands were perhaps brought there as entertainment for the Roman garrison. The Romans, like the Greeks, were aware of the existence of pygmies, and like them made a number of artworks featuring them - often involving pygmies in fight with or flight from wild beasts. The Romans are known to have enjoyed performances by very short people in the Colosseum, although it is unknown if the performances were done by pygmies or dwarfs.

Herodotus references pygmies in the fifth century BC. According to him, a group of Libyan (specifically Nasamonian) explorers had crossed the Sahara and been kidnapped by pygmies living in the swamp on an eastwards-flowing tributary of the Nile. His description of the river and swamp matches the Bahr el Ghazal - a west-to-east flowing tributary of the Nile south of the Sahara that runs from what is now Chad into central South Sudan. The Bahr el Ghazal has many swamps near its confluence with the White Nile - the infamously impenetrable Sudd.

A Catholic missionary heard of pygmies hiding in the swamps of the Bahr el Ghazal, as late as August 1931. He mentions in his article that Nuer pastoralists feared the pygmies for their use of poison weapons, but like the ancient Egyptians and contemporary Bantus the Nuer saw the pygmies as close to the supernatural. When they were able to kill the pygmies, they did so and ate them for their magical powers, much as militias did during the Second Congo War twenty years ago. The Bahr el Ghazal swamps may have remained pygmy territory until the 1960s. Given the lack of reports of pygmies in the region since 1931, it seems likely that pygmies there were exterminated. Pastoralists associated with the Anyanya separatist movement seized WWII surplus weaponry during their rebellion in the 1960s, and used the swamps of the Bahr el Ghazal as bases. Their rifles and automatic weapons were presumably enough to enable the final victory of the herdsman over the pygmy. Whether or not the pygmies were merely killed or also eaten is unknown, although the recent history of warfare in southern Sudan suggests that cannibalism is not out of the realm of possibility.

In conclusion, it appears that the location of the “Land of the Horizon-Dwellers” as well as the source of Harkhuf’s pygmy is now known as the Bahr el Ghazal. Harkhuf’s identification of that land as supporting a pygmy population is supported by the historical accounts of Herodotus and a modern missionary. If the situation in South Sudan ever allows for archaeology again, there will likely be Egyptian trade goods found in sites from the mid-3rd millennium BC. However, the origin of Wedjededba’s pygmy, Punt’s contacts with pygmies, and the origins of the pygmies of the Farasan Islands remain unknown. More research into East Africa archaeology will be needed.

In addition to the linked sources, Veronique Dasen’s “Dwarfs in Ancient Egypt and Greece” was used as a reference for this post.

Good stuff. Merci.

Stuff like this is why I have trouble disliking the internet for too long